The term “pre-war country music” casts a wide net, taking in nearly twenty years of musical and geographic diversity. It is generally accepted to have begun in 1923, when recordings of rural Southern music were first marketed directly to Southern consumers, and typically it’s generously extended into the early 1940s, when the music — by that time alternately called “hillbilly” or “hill and range,” and soon after “country and western” — could be heard not only all across America on phonograph records and radio broadcasts, but around the world in Hollywood films, starring singers-cum-actors like Gene Autry and Tex Ritter.

By 1933 or ’34, the stuff that many refer to these days as “old-time” or “mountain music” — the raggedy old breakdowns, square-dance tunes, and play-party frolics — was on its way out, making room for tighter, more professional, more swinging groups whose repertoires were stocked with more modern compositions. The mountain ballads weren’t cut out altogether, but the industrialization and centralization of Nashville as a country-music machine increased the power of publishers, who didn’t stand to make much money off of folk songs. Anyway, Southern record-buyers and moviegoers were less inclined towards the old-fashioned, antebellum-sounding material, and wanted music more in line with their own increasingly upward mobile and decreasingly rural experiences (if not identifications). The Depression was over.

Prohibition was over, too, and with it went not only the bathtub gin mills, but an era of commercial country music fixated on moonshiners, bootleggers, “blockaders,” and home-brewers. The years 1927 to 1933 spawned a huge sub-genre of records about illicit booze and boozing. These sides not only gave listeners a virtual sniff; they also were tributes to the diligence, pluck, and good old-fashioned orneriness of the country folks who knew (as did the revenue officers) that a bushel of corn or apples were worth a whole lot more when put to use in a barrel of whiskey or brandy. After all, many of these folks made the records, and bought them. And the artists — or, rather, the record labels — were awarded with brisk sales.

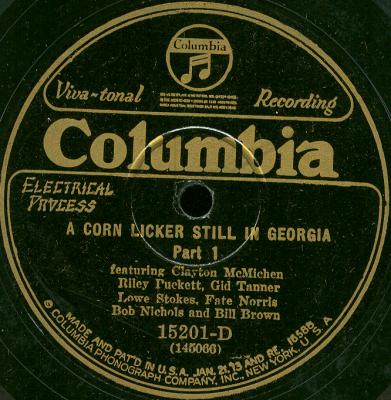

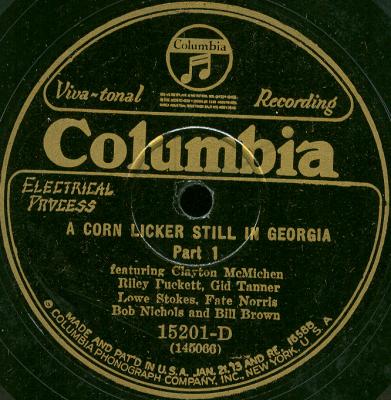

The best-selling record of this variety was the first installment of the 16-part “A Corn Licker Still In Georgia” skit-and-song epic, by the popular Skillet Lickers string-band of North Georgia. The second entry in Columbia Records’ burgeoning series of “Entertaining Novelty Records” sending up Southern lifestyles and pastimes sold over 160,000 copies. The success of the record was such to entice dozens of other artists* to try their hand at the boozy sub-genre, to varying degrees of success, both financial and artistic.

As it’s Prohibition Day (arguably — the 18th Amendment was ratified on January 16, 1920, but didn’t take effect till the 17th), I’d like to share a favorite song from this period. It’s not a skit record, but it’s one of the best to take moonshining as its subject. It was recorded by a woefully obscure group called, fittingly, the Fruit Jar Guzzlers; presumed to be from West Virginia, they made sixteen sides for the Paramount label in 1928 — the surviving copies of which show them to be a nimble if ragged string band with a penchant for canonical fiddle tunes like “Old Joe Clark” and “Cacklin’ Hen” as well as bad-man material like “Stack-A-Lee.” (This is just the kind of material that became eclipsed by country music’s modernizing trend.)

*Several fine boozy skit records, if I may say so, are featured in the “Work Hard, Play Hard, Pray Hard” set referred to in yesterday’s post: “Corn-Shucking Party In Georgia,” by Herschel Brown and His Boys and one of the last recordings of its kind, Charlie Wilson’s “The Beer Party.” Brown was from Georgia; Wilson, Kentucky. And the Guzzlers themselves appear on the “Pray Hard” volume, under the name of the “Red Brush Singers.” Two sacred sides they recorded for Paramount in ’28 were listed under this name; at least one was issued. (Paramount Records perhaps, shrewdly, didn’t think religious titles would sell so well when performed by a group called the Fruit Jar Guzzlers.)

Nathan Salsburg is a producer, guitarist, and Curator of the Alan Lomax Archive. He lives between Portland, Me., and Louisville, Ky., and is guest-blogging this week as SPACE’s Arts Administrator in Residence.