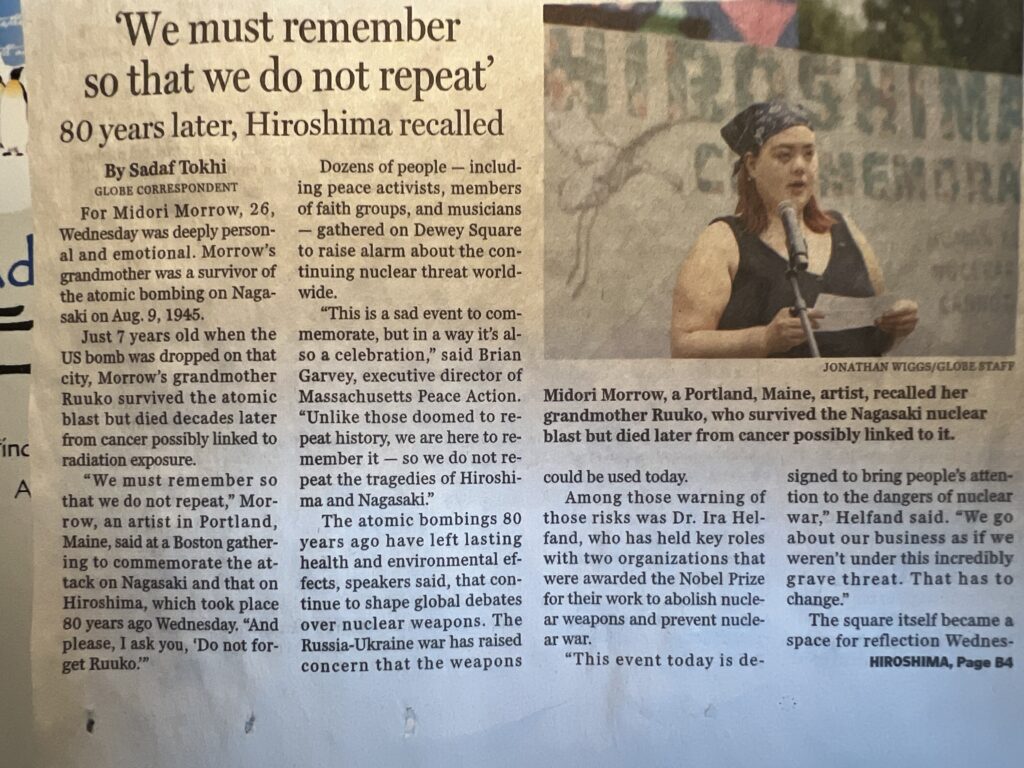

Midori Morrow is an installation artist and nuclear peace activist based in Portland, Maine. After graduating from Maine College of Art and Design’s Master of Fine Arts program in May 2024, they were awarded a studio at SPACE through the organization’s annual Rent-Free Studio Program.

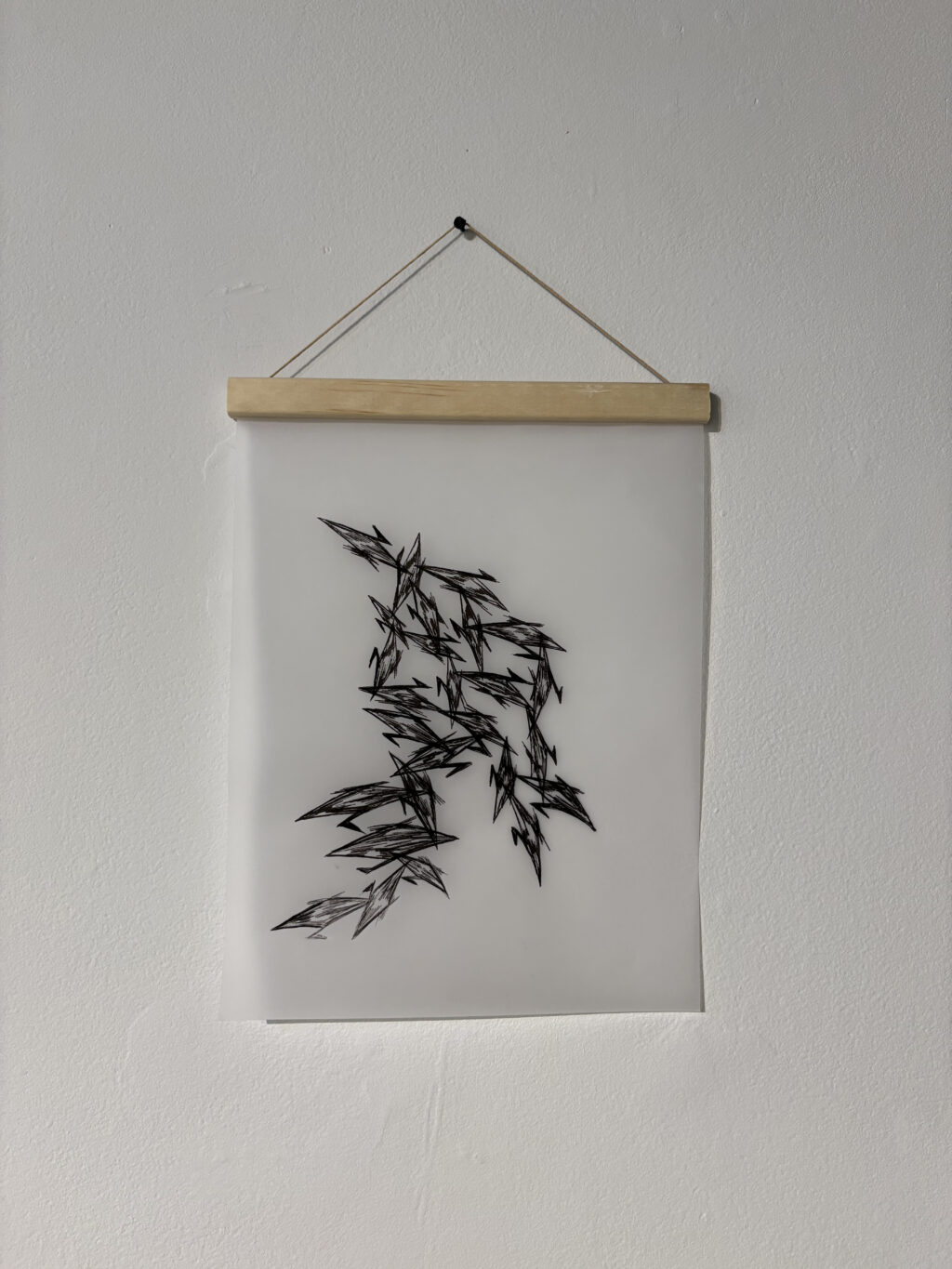

There, Morrow worked on their first solo exhibition, The Mountain Stood Still, which was shown at the Portland gallery 82 Parris from July 4 to July 27, 2025 as a part of a larger body of work made in remembrance of the 80th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. The work explored the intersection of the passage of time with inherited trauma, memories, and place.

As a continued conversation of The Mountain Stood Still, SPACE intern and Maine College of Art and Design student Willow Troise sat with Morrow to discuss their pre- and post-graduate experiences surrounding and ultimately inspiring the show.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Willow Troise: So you graduated from your MFA in 2024, right?

Midori Morrow: Yes! May of 2024 was when I got my MFA from Maine College of Art and Design.

You’re a teacher there too, right? What do you teach at MECA&D?

Yeah! I’m an adjunct faculty for the Foundations Department, I’m also the Foundations studio technician — that’s year-round. Last spring, I taught Space and Temporality. It was getting students to think about anything that involves space. We did audio, we did video, we did installation which is really important. It was really wonderful! Hopefully I will teach it again next year.

Did you ever plan on becoming a teacher?

I’ve known I was supposed to be a teacher since I was a kid. Both of my parents are teachers. I didn’t know what kind of teacher, I just knew I wanted to do that. Then I went to art school and that environment made me realize the kind of teacher I want to be.

Did you have a vision for what you hoped students would learn from you? Did that sort of shift over time?

I think when I went into it, I just wanted them to understand space in a new way. If they came [with an] understanding space in one way, I wanted them to understand it a little bit differently or expand it because a lot of people come into their art undergrad not really thinking about art in the way a sculptor does. There’s so many people who haven’t been exposed to thinking about installation and space and how you can make a viewer feel with any of the senses.

As a teacher, I imagine you learned a lot from your students. Has what you learned from your students impacted the kind of work you’ve been making?

Yes, actually! I just closed my first solo show [on July 27] and that show was almost all drawings. I don’t consider myself an artist who uses drawings in particular, and I’ve never shown drawings very publicly.

I was working with students who only wanted to draw and they incorporated drawings into a lot of their projects, [including] material that they’ve never used before. That was really cool because I was thinking, How can I tell them to push boundaries if I’m not [also] doing that?

To talk about your solo show, The Mountain Stood Still, it opened on July 4, right? Can you talk about your decision with that sort of timing?

It was actually kind of an accident, but it was such a happy accident. When I proposed the show, I proposed July or September because I wanted it to be on either side of August for the 80th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I was given July and it just happened that when the gallery emailed me, they told me the opening will be on July 4th because that’s First Friday. It just landed on it!

Especially in the political climate right now, making work that’s directly talking about a horrific event committed by the U.S. government felt like it was just supposed to happen on July 4th. I can’t not open my first solo show ever on the Fourth of July after making work for years speaking out against the U.S. government. It was such a happy accident, and I’m so glad that it ended that way.

I remember you were nervous about that at first when we talked about it. How did you calm your nerves about it?

I was really nervous! I don’t know. The work is so difficult to make because it’s about such heavy subject matter, but I was really worried that it was going to be too on-the-nose for it to open on the Fourth of July. I was making work that is highly abstracted to talk about something that’s very difficult, so I didn’t want to abstract it too much where the punch of the work doesn’t come through. I thought maybe the punch of the work also comes from the fact that it opened on the Fourth of July. It was just another act of resistance.

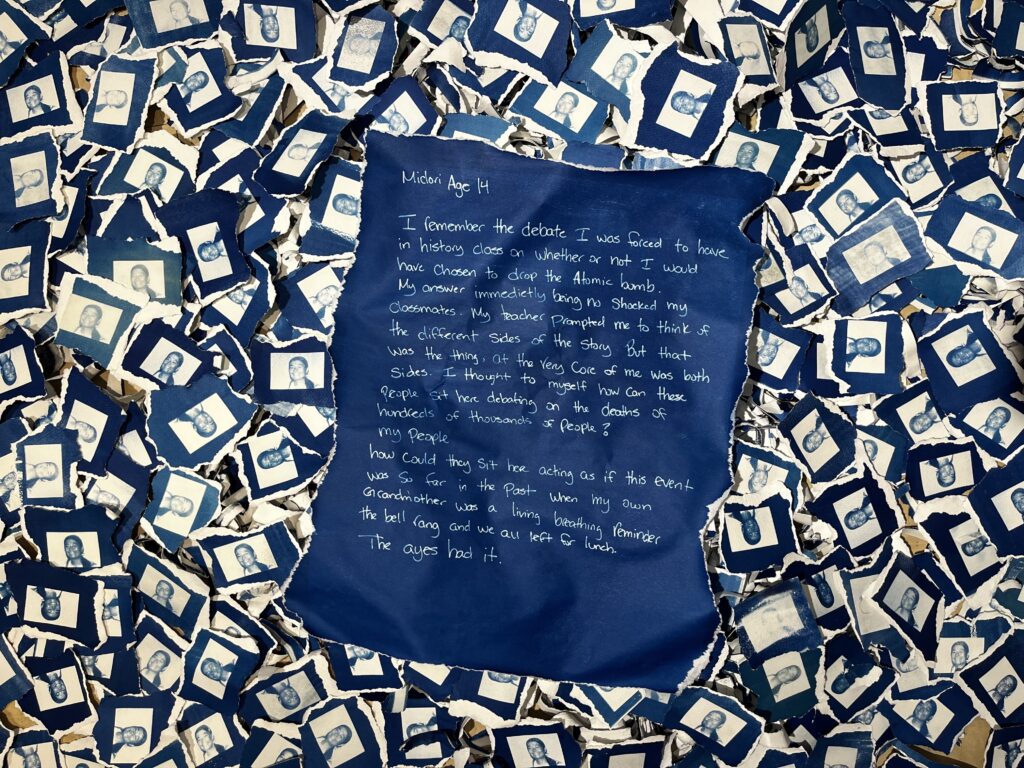

The title of the show also abstracts it in a way. And I’ve noticed that a lot of your work has poetic titles. In particular, I’m thinking about your work 2,260 Portraits of My Grandmother Ruuko. Do you consider text as a medium in itself in your work?

The title and the text is really important. When I first started making this work, it was a lot more in-your-face, and I quickly realized that that was deeply unhealthy for me. At some point, exposing yourself as the artist and putting yourself on the line is not sustainable. I think the greatest lesson I learned in grad school was that sometimes your audience doesn’t deserve to be given all the information right away.

The person that I lived with at the beginning of my grad school career, Kaitlyn Peters, was helping me install one of my very first works. I showed her some writing that I wanted to include, and I gave her this whole book of writings and told her that I was going to put the book in the work. She looked at me and said, Don’t give all this away! The people don’t deserve to get all of these stories all at once. And that has stuck with me. Everything I make, I think about whether the audience deserves to read this part of me.

That brings me to titles. I went back and forth for a few years. How much do I give? How do I point without forcing someone to think some way? I got really stuck on this idea of propaganda and not wanting to tell people what to think — just kind of nod toward where I wanted them to think instead of telling them. It’s a very thin line. But I landed on [the idea that] the titles themselves are the work. So every time now, the process is that I make the work physically. I don’t know what it’s about, but I know that it’s important. Running parallel to that is writing. I do writings, and I do writings onto some of the work. Some of the drawings in my show have writing on the back. I write, and I write, and I write, and at some point, something I write just marries itself with the work that I am making then. And that’s the title. It’s enough that it is part of the work, and they belong together. That is how I use those poetic writings. I like a long title that gives just enough to point, but not tell.

Do you mind me asking what was the idea around the phrase “The Mountain Stood Still”?

I finished my grad school thesis. I was writing about Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and I was thinking about a memorial. The day that I finished writing my thesis and had to turn the physical copy into the office was the same day as the solar eclipse. I printed out a second copy for myself and drove up to Rangeley [Maine]. I drove for like three hours by myself. And I hiked up this small trail for a couple of miles, knowing that I wasn’t going to get to a summit. I just wanted to be on the mountain. I wanted to be high up, and I wanted to be alone. I brought a water bottle, my thesis copy, and a salad up with me. Eventually I find a clearing and just sit there. When we were in totality, the entire mountain went completely silent. I have a video of it, it’s crazy. I couldn’t see anybody, but after a couple seconds, the entire mountain erupted in cheers. It was so human, and it was so beautiful. I wrote down, the mountain stood still. I went down the mountain, ate my damn salad, and went on.

Then later, I was asked to do a zine collaboration with A Clearing, and I knew that The Mountain Stood Still was the title I was going to work with for x amount of time, and it was the same time I started to do these drawings. The work was about grief, understanding it, and how we sit with that. It was so important for me at that time. I started doing the drawings, and working with silks and making prints. Then I realized it was all The Mountain Stood Still because I closed this one chapter on memorials. The memorials stayed, but now I’m thinking about time. I read this book about the universe — casual, super light reading. It was about time and the universe. I read that time moves faster in the mountains than it does at sea level.

Is that a fact?

Yes. Just by the teeniest tiniest amount, but it’s true. It all connected. That’s when the writing about time and this mountain had come to symbolize resistance and an immovable force. That’s when that, paired with every physical thing I was making, crossed over.

Text is super important for you, installation is super important. I know in the past, you’ve seemed a bit hesitant to call yourself a photographer. What sort of mediums identify more with now and why has that changed?

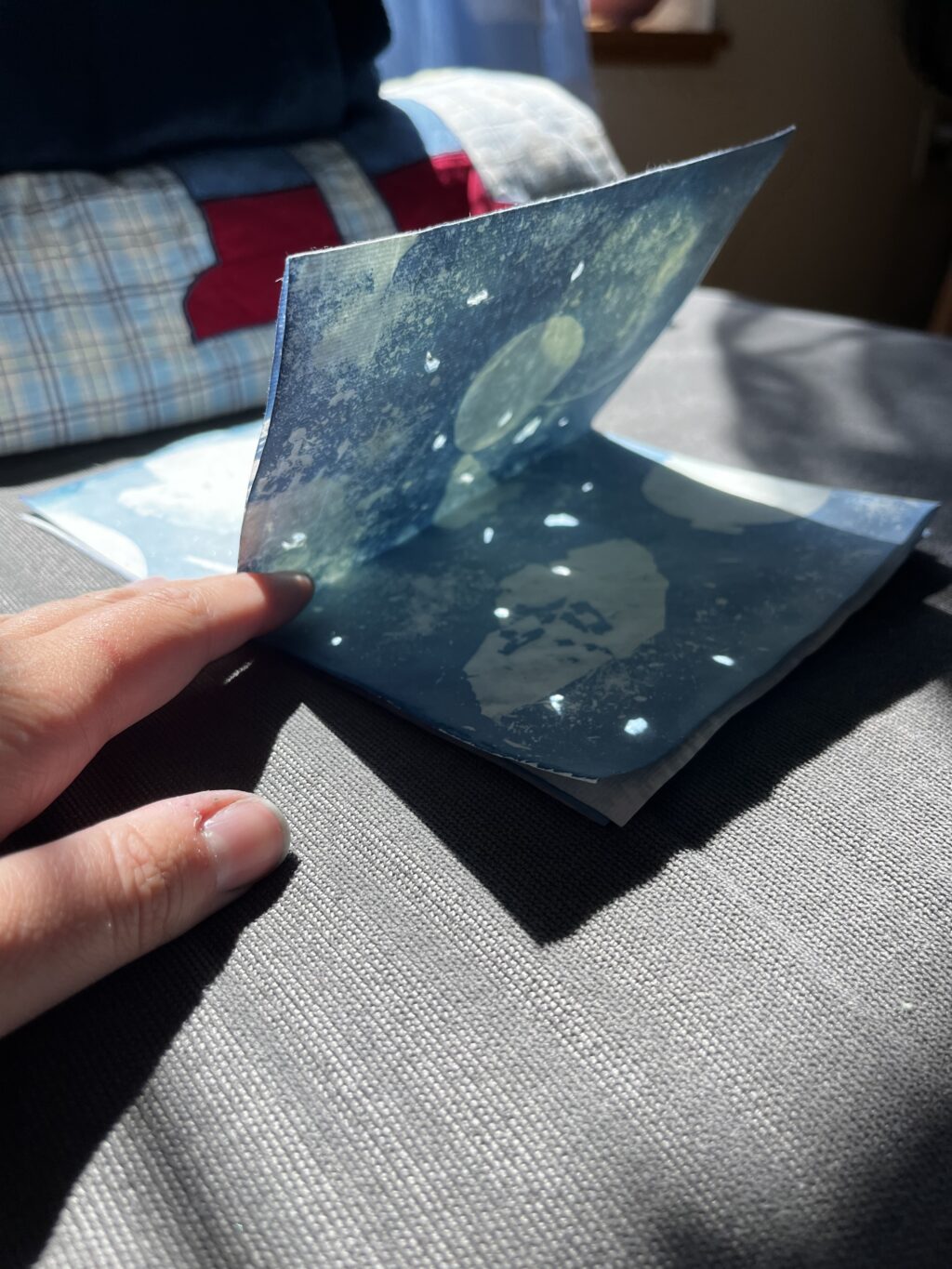

My undergraduate degree is in photography, and I think I still am a photographer, but I’m not a photographer in the way that I was years ago. For me, the core of photography is light. Everything I do involves light, and now it involves time. The way that I approach everything is from the eye of a photographer, even though I’m not technically taking a photograph.

I had a breakup with photography for a while because it felt like it was a really exploitative medium. I was looking at all of these images of war and of people dying, or of people who have died. It felt so wrong to me that I almost needed to step away from the medium completely so I could understand what it means to take a photograph of another person and the weight behind that. I have a completely different relationship to it now. I would call myself a photographer always, but not in the way that I imagine a traditional photographer. It’s a very complicated relationship.

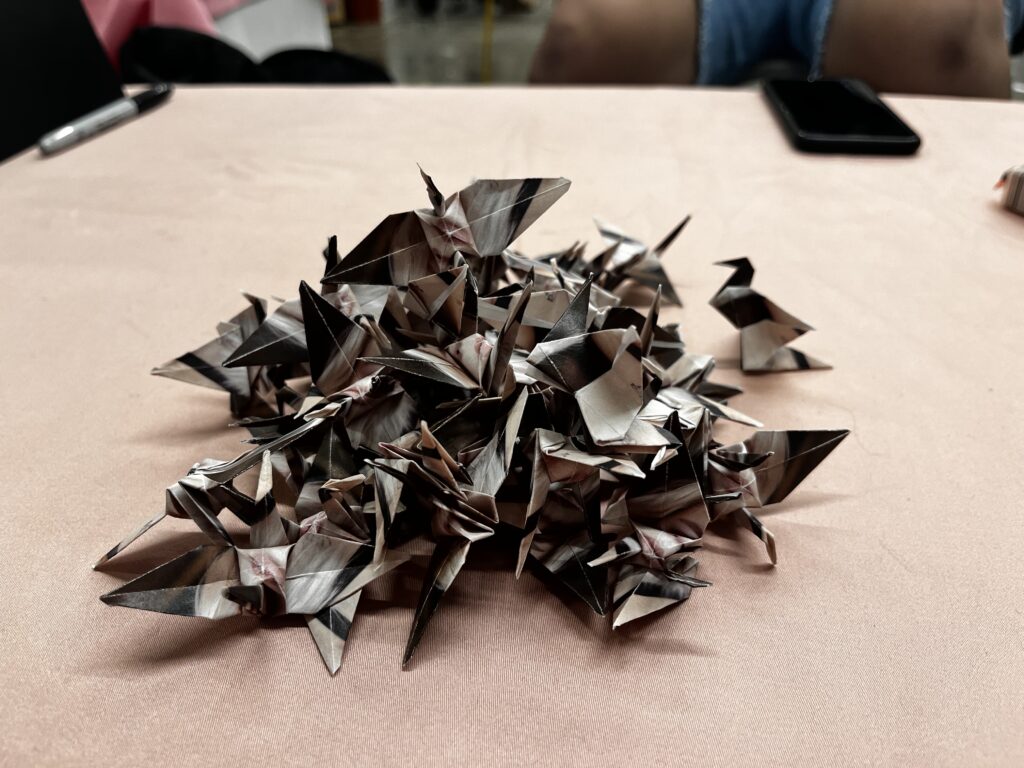

I totally agree about photography being potentially exploitative, especially when it’s paired with really heavy statistics. I feel like factual statistics and repetition comes up frequently in your work. Do you think that sort of repetition and use of fact is intentional? Or is it a subconscious thing for you?

Repetition, for me, goes back to folding paper cranes. It’s this thing I’ve done multiple times in my life when I’ve wanted this wish and this hope. Doing that, and figuring out alternative ways to make paper cranes without folding paper cranes has been what I’ve been doing every time I use repetition. It’s sitting with the work, it’s the artist’s hand touching every part of the work, and it’s the time, and it’s the labor. It’s this, almost, desperation: If I keep doing this one act, if I keep repeating this, if I keep at this, I can work toward something that matters. It feels almost like I am working toward that wish.

It can mean so many different things, and that’s the beauty of it. Using this motif over and over again. Even if it’s not technically [folding] a crane, I’m still repeating this same act over and over again, and it’s meditative.

And to talk about the use of fact: Yes! I love basing my work in fact. I want to teach this to any student I work with: if you don’t know what something means, don’t use it. If you know what it means, that’s what’s most important. That’s when you should use something. Since I’m making work about history, it’s very important to me that I know what I’m talking about, and I can actually talk about what I’m talking about. Then I look at it from a bunch of different perspectives, so I can speak on it. Obviously mistakes happen, but I don’t ever want to use something when I don’t know what it means because I think that’s extremely irresponsible.

In 2,260 Portraits of My Grandmother Ruuko and in The Mountain Stood Still, I believe you used cyanotypes and those seem to be becoming a staple to your visual language. How did you happen upon it, and what role does it play in your work now?

I wanted to figure out how I could harness a type of radiation that is safe, while talking about a type of radiation that is not safe: solar radiation versus nuclear radiation. It’s a way for me to use and harness and control this radiation while also giving up a little bit of control because, with cyanotypes, they’re so unpredictable. You only have so much control there, so working truly with this medium and thinking how it’s about exposure, radiation, and a stain left behind felt so natural because it made so much sense when talking about a nuclear blast. How can I take this medium and use it on things that might not survive? They need to withstand this intense process of being exposed. How strong and resilient are those things?

Cyanotypes have that really strong, distinct blue. How does color relate to your art and life? Do they play similar roles?

I’m coming at it from two angles. I love color. As a person, I feel like I’m so colorful and I love bright, aggressive colors because I think it’s fun and exciting. To me, color makes me feel beautiful. I’ve been told so many times that I don’t dress like my work. If you were to put me next to the work in the way that I exist in everyday life, it wouldn’t look like I made that work. And I love that so much. I make this work that is reflective of what’s inside me. The outside of me is bright and exciting, and that makes me feel beautiful on the outside.

But on the inside, I feel this intense blue. It’s beautiful, and calm, and holds this presence and weight that’s so important. It is just there. It commands a presence. When I make the work blue, I want it to be this calming presence. I’ve tried to make work in other colors. I look at it as a sustainable art practice for me. If I were to make work that was how I felt about nuclear war and it was red, that would be so angry.

I don’t get to walk away from that work, while the audience does. I never walk away from it completely, but I need that kind of separation from it because it would destroy me if it stayed with me every single moment of every single day. There’s so many different reasons why I use blue. There’s the calming aspect, the water, the cleansing aspect, but that’s the big one.

I like that you brought up the color red because I remember you wore red to your exhibition opening. I assume that’s related?

I wore red because I didn’t want to match the work. Red, to me, is strength. Red is my mother — such a radical, wonderful strength. When I’ve put up work before, I’ve always matched it. I’ve worn blue, or worn green, or worn softer colors to match the work and to feel like the work — which isn’t usually me. When I did my first solo show opening, it was the 80th anniversary of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In Japan, red symbolizes strength, wisdom, and a commanding presence. Wearing red to my opening was this way I got to command presence.

To me, red is energy and passion, but often anger too. You were wearing red, you weren’t trying to be calm about the situation. This was the work that you made to be calming, but the way that you feel is anything but that.

That’s where the anger comes in! For me, the most effective anger is when it is confident. A calm anger, almost. Showing up like, Yes, I’m angry. Yes, I want change, is the way to harness anger instead of having short bursts of outrage. It’s a consistent anger that we’re all feeling.

In the critique I had early in grad school for 2,260 Portraits of My Grandmother Ruuko, someone said I noticed you used blue. Why? They looked me in the eye and said Are you not angry?” Then it hit me — that crazy, intense anger. Like, angry? Of course I’m angry any time I think about nuclear war, nuclear weapons, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and my family, the people that died that I never got to meet. Of course I’m angry.

And that is when I realized I will never walk away from this work fully and completely. An audience can walk away after two seconds. They don’t even have to look at it. If I were to make that work red, or angry, or any other color but blue, then I would never walk away from it and they would still be able to. That isn’t fair, and that isn’t how I show my anger.

Did you have that critique in mind when you were getting dressed?

Yes. And that’s where the red showed up, that’s where it was important for it to. Anger like that is the best feeling, it’s the most productive one. It’s this anger that, if I harness it and have control over it, I can do anything.

In the moments that they are standing with your work, how do you hope that balance impacts how people come to interpret your work?

I want to draw people in. We’re living in a time where we are so bombarded with images of horrific events. Not to say that those should not be seen and that they aren’t important, but we are so bombarded with them that, at some point, too many visually disturbing images will turn an audience away before they even get the chance to come into a room. It’s almost a way to grab people.

Then they come in and it’s quiet. It’s a place to think and reflect. Then somewhere — whether it’s in a title, the wall text, written in the work, hidden in the work — after someone is drawn into the beauty and calmness and their guard is a little down, I can pack the punch that this is about nuclear war. My family died from nuclear weapons. Nuclear radiation lives within my body. That’s when I get to hit them with that. And it works.

I don’t know much about nuclear radiation. Do you mean it lives with you literally?

There’s not a lot of research into it, but there is a chance that what happened to the people in Nagasaki and Hiroshima gets passed down genetically to their descendants. It’s not confirmed, but there have been a lot of cases where the children of hibashuka — which are bomb-affected people — have had health problems, and then their descendants have health problems. It’s not proven, but it’s really likely. At some point in my life, if I get sick or my family gets sick, we won’t know if that’s why.

Then there’s also the generational trauma that lives within your body. It’s something that I’ve had to come to terms with over the last couple of years, and it’s really difficult to come to terms with because nobody knows. It’s terrifying. I think that’s also why I make the work, and why I make it blue. I need to, at some point, step back a little bit. I need to not be right there on the work all the time.

When I watched one of your artist talks, there was this line you said really stood out to me. You said “The danger of forgetting puts us at risk for the danger of repeating.” Where do you stand with that statement now?

I stand the same way I stood when I wrote it. We are in constant danger of repeating because we are actively repeating it right now.

This also feels like it ties to repetition, too.

It all connects and it drives me crazy when I’m working. We’re in a time right now — and we’ve been leading up to it for so long — where we have been slowly forgetting the atrocities that we’ve committed. It happens every time: an atrocity is committed, everyone agrees not to do it again, then we’re happy, and it’s wonderful, and then it starts again. Right now, we’re seeing one of the worst genocides in history. There’s so much behind it, and there’s so many different layers of complications in how people approach this. People are almost terrified to say it’s a genocide, but it is. The fact that we are repeating past atrocities in so many different places in our lives is causing us to almost shut down. Because we see so much of it, we’re paralyzed with fear. So how do we turn that paralyzing fear into fear that pushes for change? Into anger that pushes for change?

So what can we look forward to seeing from you? What’s next?

I’m moving forward with making work about time. I’m so glad that this is the last question after the question about that quote. I think about that daily — the danger of forgetting and repeating. It turns into a conversation about time. What do we learn over time? What do we forget over time? How do we change things over time? Time is genuinely so important for everything we do. The work I’m moving forward with right now is about time.

More work by Morrow can be found on their website midorimorrow.com or on their Instagram page @_midorimorrow_.