Roopa Vasudevan is a new media artist and scholar based in New England, where she works as an assistant professor at UMass Amherst. Vasudevan is interested in examining our relationships with technology and encouraging careful reflection in a world where change is rapid and often feels out of control. She spoke to SPACE intern Claire Crawford in September about her work and her show at SPACE.

SPACE: You describe yourself as a “new media artist.” Tell me more about what that term means for you.

Roopa Vasudevan: There’s a lot of contention around what being a new media artist means. A lot of people tend to define it in very different ways. Some people have a very expansive way of looking at it, where, if you are making things with digital media, you count as a new media artist. It’s a very inclusive way of thinking about it, which informs the way that I consider it. But I also come from a world that is beyond just the focus on working with computers and working with digital media. I come from a space where people are really interested in getting to the guts of these systems and figuring out what’s going on with them and using them in more creative applications.

In my PhD dissertation, which was about the new media art field, which I’m currently working on converting into a book project, I defined the new media artist as somebody who is expanding or reinventing or misusing digital systems. I think that gets to a lot of the ways that artists are working creatively with technologies. They are not just using them in the ways that are prescribed to them but are doing unconventional or subversive things with them that either haven’t been seen before or weren’t intended by the people who originally made and released those tools.

You incorporate interactive elements in a lot of your work. I’m curious why this is important for you and how it serves your broader artistic philosophy.

There are two reasons. The first is that when I went to graduate school for art and I took my first coding class, I really fell in love with it. It was cool to me to be able to build something to put in front of somebody that they could manipulate, change, or create outputs or versions of the work that I would have never considered.

Running parallel to that is that I really have a love-hate relationship with technology, and I think a lot of us do at this moment. It feels like something that is overwhelming, that is advancing and developing at a pace that we can’t even wrap our heads around, that we have no agency in contributing to. We just have to keep up with whatever the billionaires and the companies are telling us that we have to do. We must put these systems into our lives, because otherwise we’re going to get left behind and we’re not going to keep up with the way that society is advancing. I fundamentally, strongly believe that no technology is inevitable. The things that get put in front of us are not the only way that it could have gone. It is serving a very specific version of goals, priorities, and plans coming from bigger companies, and particularly these tech billionaires who are at the central focus of a lot of the conversation around technology these days. They have a very specific version of the world that they’re trying to put into effect. They see the world from their very limited perspective. So, they’re building these tools and enforcing an adoption of these tools to get society to more align with that vision.

When I’m creating interactive works, or creating works that can incorporate user input, I’m talking to people. I’m getting their stories. I’m asking for their participation in these experiences that I’m building. It’s a way for me to remind us that we do have agency in deciding whether we adopt this version of the world or this vision of the future that is being laid out in front of us as the only option. It’s a way for us to be able to collectively push back and to be able to say, actually, no, this is the thing that we want and I’m going to tell my story, and I’m going to participate in moving the needle ever so slightly toward the version of the future that I actually want to build.

Since we’re talking about tech billionaires making big changes, I want to ask about AI, because I’m just so curious what you think it means for artists.

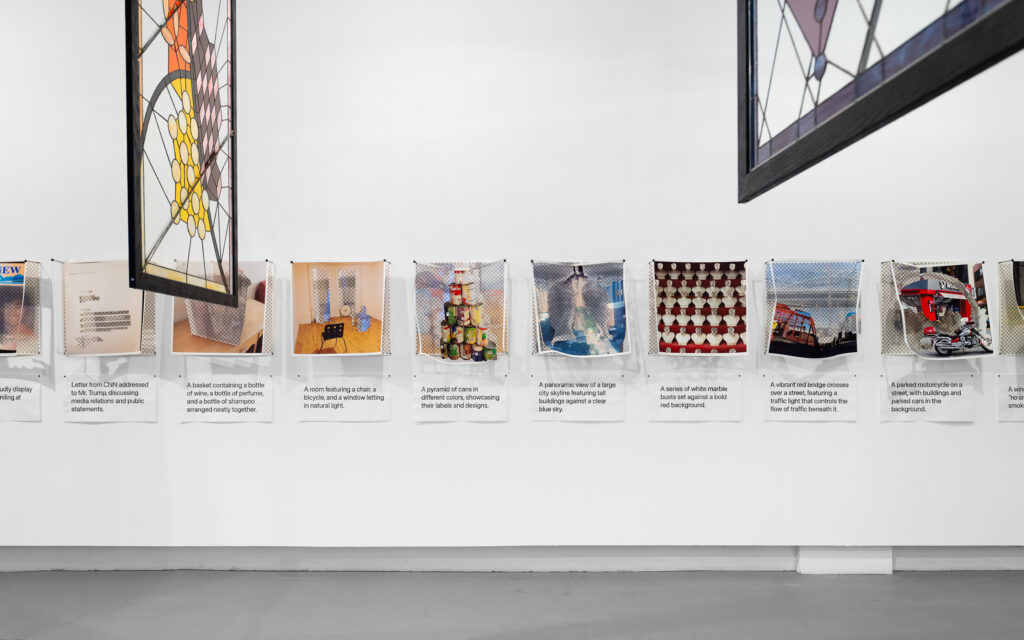

For the show that I am preparing at SPACE, the central theme is really thinking about AI and the metaphors or ideas or visions of AI that have been determined over a long period of time and often heavily shaped by those in power. We’ve let those dictate what we imagine AI to be. The stories that we tell ourselves about AI, or the metaphors that we use to describe it, or the fears that we have around both our experiences as humans and our experiences of technology that we’ve had so far, we let those things guide the way that we think about AI and about technology more broadly.

There’s so much that you can unpack with this idea of artificial intelligence, even just boiling it down to the word. When we say intelligence, what are we actually talking about? When we talk about AI, we think about intelligence as those things that can easily be quantified — that can be put into numbers and can be easily sorted and classified and categorized. This is a very computational binary logic of the way that the world operates. As human beings, we know that that’s not the case. We know that the world doesn’t work like that. There are plenty of gray areas. There are plenty of ineffable qualities about humanity that often get erased when we think about intelligence in this very limiting manner.

To answer your question about AI and art, I think this breaks down into two big concerns. First is the power concern. People who are developing these technologies are doing so in ways that do not get consent and do not ask for permission to train their models on work by artists and by creative practitioners. They assume things about the way that the future is going to unfold that are going to be detrimental to people trying to make their living in these creative fields. That is a question that is less about technology and more about power, economics, and free labor. It is about how people who have a lot of money and a lot of power often think that the people doing the work are expendable. That’s not as much of a question about the technical aspects as it is about the priorities of the people who are making these tools in the first place.

When it comes to the technology, I get really prickly when I hear universal blanket statements about AI art being bad, because you have artists like Stephanie Dinkins, Morehshin Allahyari, and Carla Gannis who have been working with AI and thinking about the implications of these tools and of machine intelligence for decades. There are people who’ve been doing really incisive, important work unpacking these technologies, thinking about how they’re working and how they’re made, and doing something creative to point to the flaws or to envision new possibilities for them. That also is AI art, but it’s not the AI art that people are thinking about when they’re so focused on the power aspect of these things. That association erases the more creative use of these tools. So, I really think it’s important for us going forward to think about quote-unquote AI art as not this big monolithic thing that only encompasses things generated with ChatGPT or Stable Diffusion or Midjourney, or all these tools that have been very, very controversial, with good reason. We have to think about AI art as encompassing that as an aspect of it. But then we also have to think about the work that people have been doing on a much deeper level to investigate these tools and what they can say about society. I think that that is a super, super important part of this discussion that’s largely getting glossed over.

I totally agree. On social media, I’m seeing a lot of the AI-generated images, which makes it hard to remember there’s a lot more to it.

With those AI-generated images, it’s a question of authorship and ownership that is not necessarily restricted just to this type of image generation. There was controversy around the camera when photography was first introduced. People were going wild, saying that photography is not an art form because you’re not doing the painstaking work of painting a realistic-looking landscape or a portrait or something like that. But photography just led artists and painters to move in different, more abstract, interesting directions with their work. So, I don’t necessarily think that these image generators are a death knell for art-making practice in the way that they’ve been talked about.

I do think part of the reason that people have so many problems with it is again not necessarily about the technology. It’s about how the technology is constructed, about the priorities of the people who are making the technology, about the power differential. It’s about how people are seeing their work being taken and scraped into these data sets without consent, minimizing the effort that they’ve put into their own art-making and their own creative practice. I think all of that is leading to this larger conversation, but I don’t necessarily think it’s the whole conversation.

You mentioned that you started to learn to code in graduate school, so it seems like coding was always part of your artistic practice. Do you think coding is artistic in itself or more of a tool for art?

There are people who go back and forth on whether coding, and technology more broadly, should just be used as a tool in the toolkit, or whether it is a form of creative expression in and of itself. Going back to this definition of the new media artist, there’s a lot of power in being able to take something that exists in the world and envision a different use for it, or to be able to manipulate it or to use it toward a more expressive end. I think that limiting ourselves to what is an artistic tool versus what is not an artistic tool is a very myopic way of looking at things. For decades there have been artists who have been using code and using computational systems to create really interesting work, whether that’s thinking about formal qualities of a medium, or whether that’s using code to collect and analyze data, or whether it’s using it to create interactive or live visuals that have a life of their own or react to user input.

The artist Vera Molnár has been a big inspiration for me. She used automated pen-plotting systems to create these really intricate, fascinating drawings, and to think about the limits and possibilities of automated systems. This was way back in the ’70s. There have been initiatives since the mid-20th century to bring artists into industrial environments and to work with new technologies. So, I think that, like everything in the world, there is artistic possibility in that expression, and code is just one way of doing it.

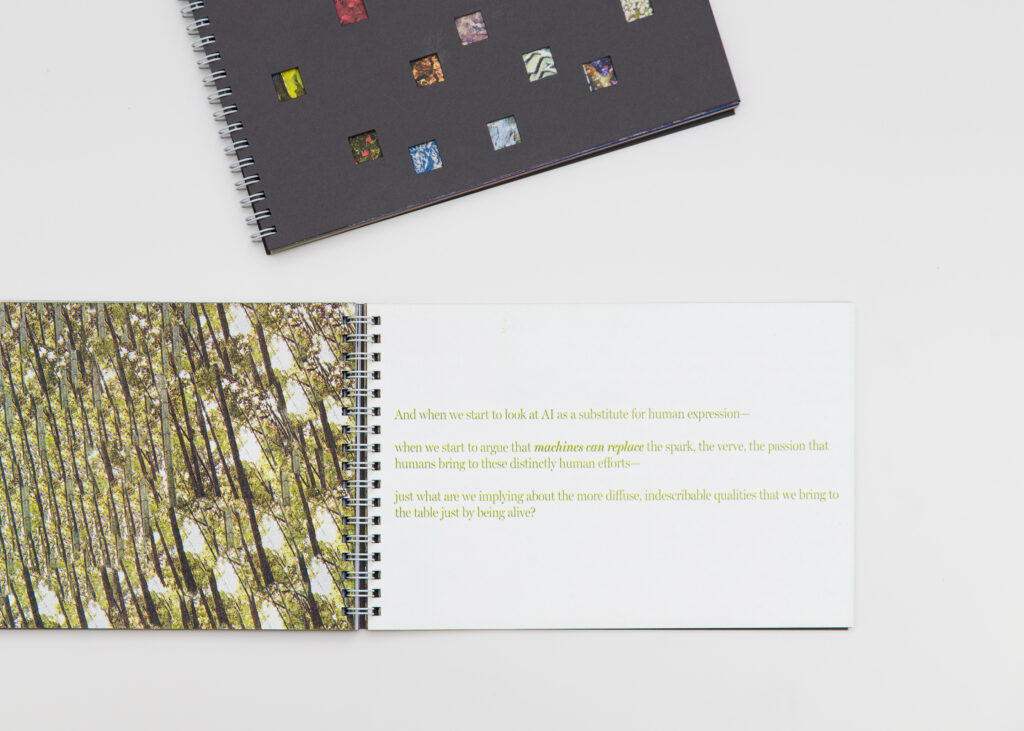

Tying back to our questions around AI, DIY and artist-run spaces are the primary spaces that I really love to work with. Obviously, I exhibit other places too, but I love working with DIY and artist-run spaces, just because they have an intrinsic value system that I think really pushes back against a lot of the gatekeeping that happens in the art world. It’s thinking about supporting artists who are often left out of these larger institutional conversations. This comes from my discovery in high school of punk and independent music. These artists don’t want to rely on the major labels or the big institutions to share their work. They’re doing it themselves, and they’re cultivating an audience that really believes in them and believes in their work, and they’re sharing their work directly with their audience. So, they’re starting their own labels, they’re demystifying this process of publishing their own work, doing it themselves, getting right in direct contact with those manufacturers, being able to press a limited run of albums and sell it out immediately. Or in the case of self-publishing, which is also something that I’m invested in, it’s very similar. Rather than waiting for some big publishing house to publish your book, you do it yourself, and you make connections, and you design the work yourself and create a pipeline for yourself that is not reliant on the big systems to validate or legitimize your work.

There has been a lot of discussion recently about whether coding education is even necessary, because with the advent of things like ChatGPT and AI, a lot of software developers are saying AI is going to do all this technical work for us now. But I think that now learning to code probably might be the most punk thing that we can do, in particular when we’re thinking about our technological future. There is merit to doing it ourselves, not relying on these larger systems that have been constructed for us to build the technology. If there’s something that you want to see in the world, build it yourself and take that ownership of it and exert that autonomy and that agency. There’s something so empowering about that. I teach my students at UMass that there is something really, really great about being able to build something yourself and not having to rely on a big tech company to give you the systems to get somewhat close to where you want to be. Being able to code is taking a lot of power into your own hands, both artistically, but also in terms of a larger existence in the world in this day and age. And I think it’s really powerful if more and more people refuse this notion of AI being able to do all of it for them, and to say, I want to do this myself. I want to learn these tools. I want to be expressive with technology, and this is the way to do it.

Since you’ve mentioned your students at UMass, can you tell me how your scholarly work and your teaching contributes to your studio practice, if at all?

I’m always inspired by the students that I teach in my classes. The classroom helps me think more broadly about what I’m thinking about in the studio. It’s also a great way to share the things that I’m thinking about with a group of people who can bring new perspectives to the table that I might not even be envisioning. I teach a range of classes at UMass. I teach an introductory creative coding class where I’m teaching students how to program in an artistic context. This fall, I’m also going to run a class that I’ve run once before, about self-publishing as a creative practice. That class starts with the development of quick and dirty zines, and then we work as a collaborative group to create an artist book together. I end the class with teaching a little bit of introductory web programming and thinking about publication from an autonomous, do-it-yourself perspective — not relying on the industrial publishing complex. Really putting your work out into the world, growing an audience, building that up, distributing, and what that means to get your work out into the world. We talk about all of that in that class, and I’m really excited to be able to teach that in the fall. Last year I launched an independent artistic press imprint, so that is building off my experiences doing DIY publishing, both online and offline. I want to bring that experience to the students and engage them into a larger conversation about what it means to self-publish your own work, and why you might do that, particularly in the political climate and in the moment that we’re in right now, and the power that it gives you to be able to take those reins, and put your words into the world on your own.

I’d love to know more about how you got into self-publishing.

I got into the web aspect of it first, I started building a lot of websites. But I was an avid reader growing up. I grew up in the ’80s and ’90s, and there’s still something so appealing to me about tangible media, having a book or a printed document in front of you. There’s still something so beautiful to me about being able to put something into the world that somebody can then have in their hands. It’s such an intimate experience. I think technology can come close to replicating it, but it can never really encapsulate the full beauty of having an actual book or product in your hands that you can grasp and read and hold on to. So I started producing zines. I found that I could translate the things that I was thinking about in my technological studio practice into a printed format and vice versa. I’ve always been really interested in prints and printmaking, but when I started to get into Risograph printing several years ago, that’s when it really took off. There’s something amazing about combining the beautiful tactile approach to designing for Risograph and being able to print a large run of things all at one go. That has pushed me into taking self-publishing more seriously as a practice and led me to launch my imprint in the first place last year.

I just have one more question for you. How did you get connected with SPACE?

I know Kelsey, the director at SPACE, from our connections in Philadelphia. Kelsey used to work at Vox Populi, which is an amazing artist-run space that’s existed for over 30 years in Philadelphia. I was an artist member at Vox from 2019 to 2023 when I lived in Philly, while I was doing my PhD at the University of Pennsylvania. I’d known of her work — the amazing projects that she’d done around women, art, and technology — and knew of her as a kindred spirit that was working in this area and was interested in a lot of similar themes that I was. So, in 2022 I invited her to participate in an exhibition I was curating that took place at [the University of Pennsylvania]. It was three artists with deep connections to Philadelphia that were all thinking about computer vision and thinking about what it means to have a machine “see”. Thinking about what we’re leaving behind when we use that metaphor and what we mean when we say that computers can even “see” in the first place. A lot of similar themes are informing the show that I’m putting up at SPACE right now, in that it’s dealing with a lot of the metaphors that we use around computation, and what we are leaving behind in the process when we use these metaphors of human sense-making.

As part of the show, Kelsey exhibited a project called KeLCD/Third Eye, where she created a bespoke camera that attempted to create aura readings of places or things that she pointed it at. She took it to important places in her past and in her history and created these Polaroid images that she then displayed with aura readings. After that Kelsey and I kept in touch, and when I moved to New England, we started having conversations about my doing work at SPACE now that I was based in the area. When she heard about the things that I was thinking about around AI and humanity, she was really excited and interested in potentially bringing that to the community in Portland. That’s where this project emerged from, that I’m really excited to be debuting at the gallery. I was also really lucky to be one of the jurors for the Kindling Fund last round, and I got to see some of the amazing work that’s being produced by Maine artists. I was really excited to read the applications and see some of the incredible stuff that people are doing in Maine, and so I’m looking forward to bringing my work up to Portland, and to be able to continue that conversation with the community of artists and people who are interested in art in the area.

Roopa Vasudevan’s Artificial Abundance is exhibiting at SPACE, 534-538 Congress St., from September 5 through October 11, 2025.