Based in New York City, Cooper Holoweski is the creator of our current window installation Let Our Love Guide You From This World To The Next and the brain behind Katabasis, a film that’s designed to be viewed alongside a live musical score. Katabasis explores themes of death, limbo, and rebirth by navigating the viewer through a digitally constructed fictional wasteland.

Cooper was kind enough to answer some questions about the intentions of his work, the disparity between digital and analog creative endeavors, and the concept of utopia. Here’s what he had to say:

You work in a vast variety of mediums – some digital (animation, video, computer design) and some analog (painting, drawing, making works on paper). Do you feel a different kind of connection to your studio practice when you are working in virtual media and when you’re not? Or is your creative process something that operates independently of those factors?

I think the distinction between a digital and traditional means of making work has sort of withered away for me. Even when I’m working on canvas with paint there is a lot of prep that involves a computer. Sometimes its just googling source material but it usually includes composing some sort of a digital photomontage that gets transferred onto the canvas and worked into with layers of paint. So even painting for me involves a lot of computer work. Conversely there are a lot of material concerns that go into my more digital-looking work.

That being said, I do really enjoy the tactility of stuff. I find myself getting pretty bummed out if too much of my studio time is spent looking at a screen. For the longest time people would say “a computer is just another tool, like a pencil or a paint brush” and it’s not. It’s more like a surrogate brain that is really adept at some things and totally incapable of others.

Your project Katabasis is formatted in the program Google Sketchup. Can you give us a little background of how Katabasis came about, and how you chose this program to execute your idea?

For the past five years a lot of my work has referenced the theme of collapse. This usually involves the narrative of a grandiose construction that builds itself up and eventually buckles under it’s own weight. That focus sort of ran it’s course with me and I started to wonder about what happens next.

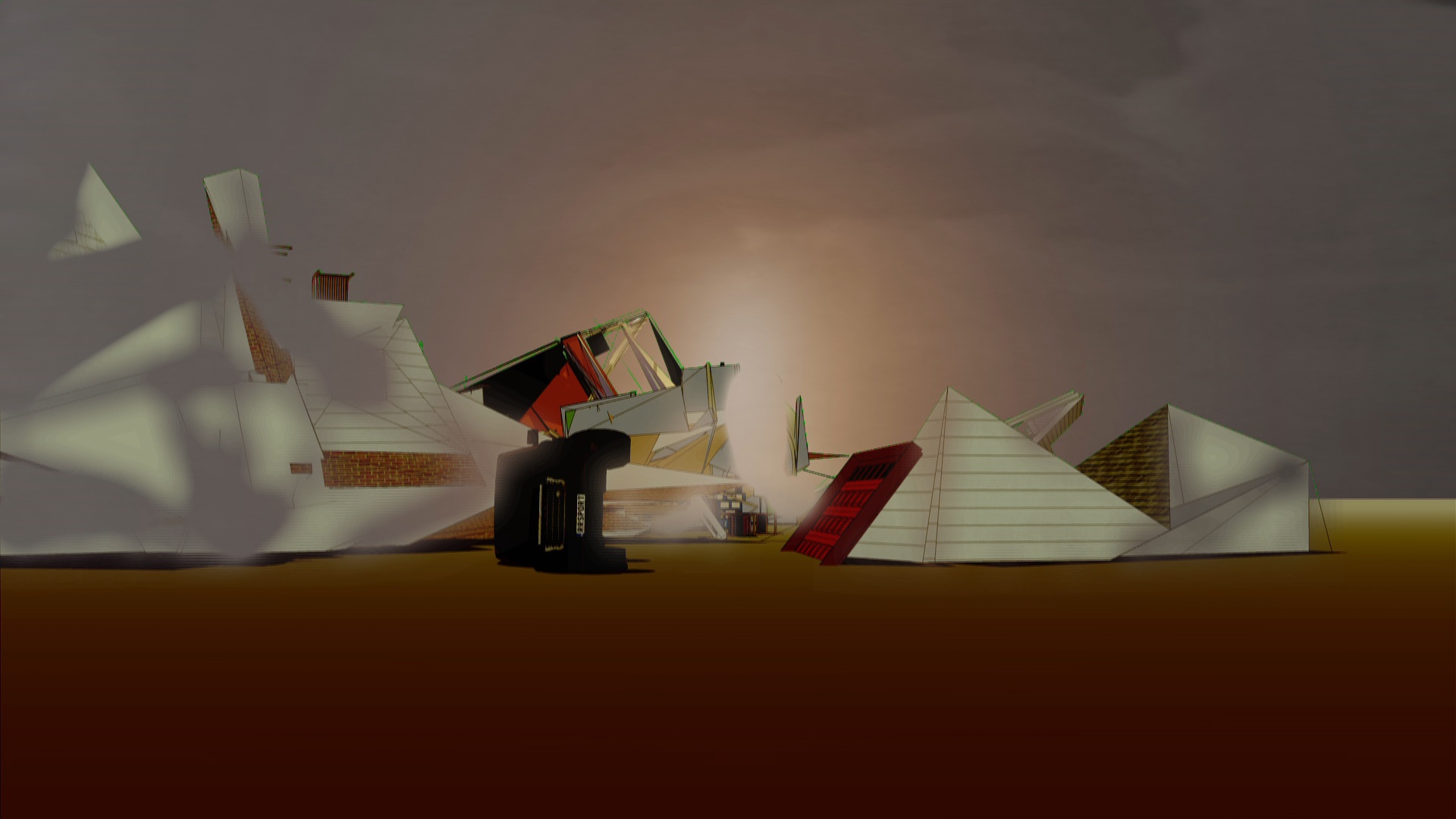

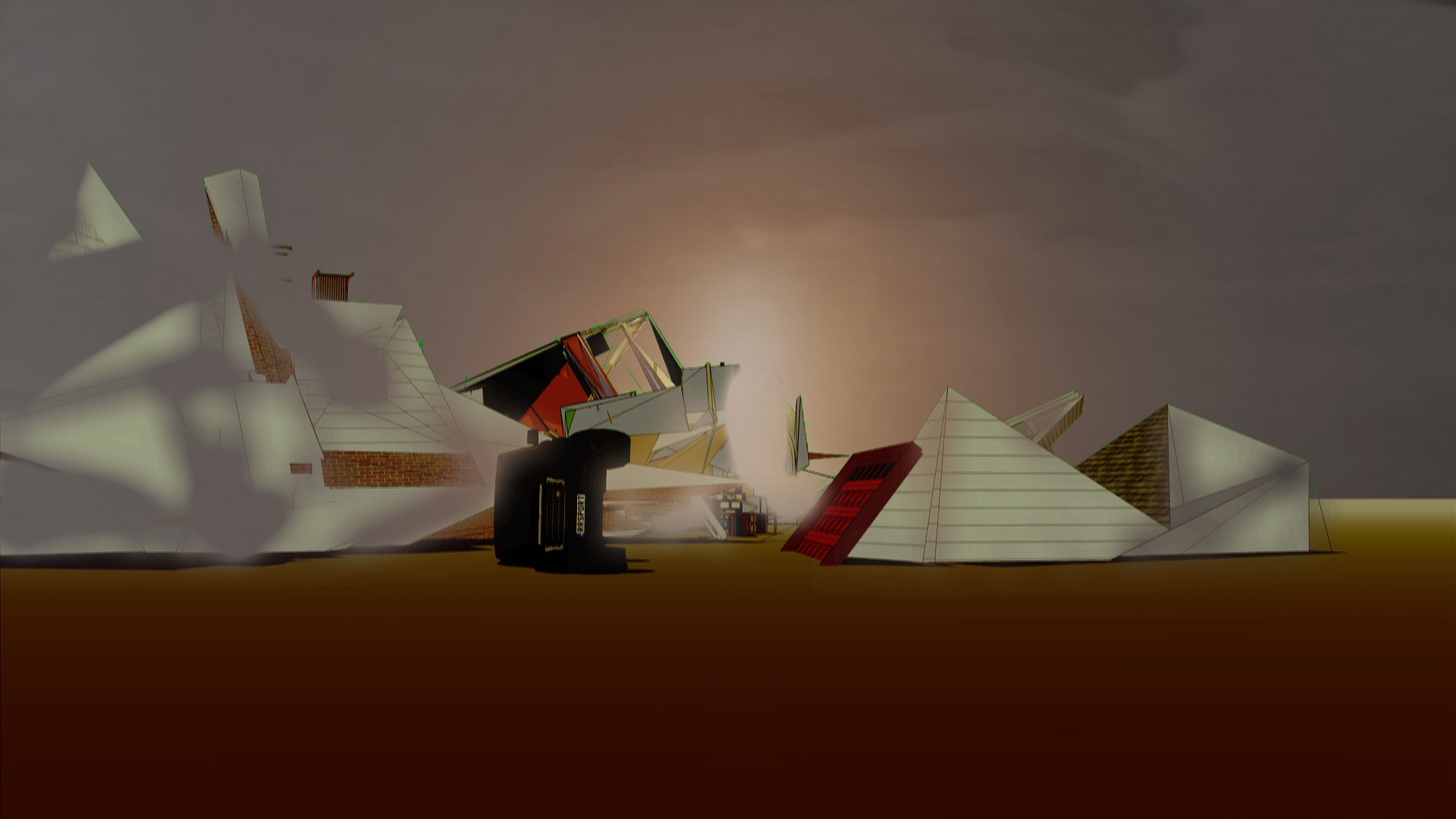

Around the same time I started to dig deeper into the world of 3D modeling and had accumulated this monumental collection of virtual objects. I started working with Sketchup basically because it was easy and free. Sketchup is certainly not without it’s limitations but what kept me going with it was the 3D warehouse, a website where you can download other people’s models and work with them. So I went nuts downloading models from the 3D Warehouse and it got me thinking about the life cycle of things because while the physical objects around me were constantly in a state of decay, my Sketchup files were frozen in time. I started to deconstruct some of my Sketchup files and make these virtual garbage piles to sort of mimic the passage of time. Those little compositions never really went anywhere themselves but they had this weird tension of something ending and beginning at the same time. I really liked that feeling but wanted something that felt like more of an environment, like the Bardo for consumerist goods. So I designed the space for Katabasis and decided this is what happens after the collapse.

Katabasis also features a live musical piece (which will be at SPACE on the First Friday in April). How does including a live, performative component define or contribute to the viewer’s experience of Katabasis as a place?

For me the performance of Katabasis provides a really cathartic experience. I think the fleetingness and ephemerality of a performance are qualities befitting of the subject but more than anything the live score provides an atmospheric tone that really does justice to the piece as a whole. My brother and I collaborated to create a recorded score for the DVD and for screenings where a performance might not be possible. It’s a great piece but it’s very different. In general I think its asking a lot of a viewer to watch a piece of non-narrative video art lasting over five minutes; you sort of wander in and out of it. There is a real structure to Katabasis and the live performance pulls you in for the entire forty minutes to experience the piece they way it was intended.

There are three movements that compose the musical score –death, limbo, and rebirth. Can you talk about the decision to reference those three themes in this project?

For me the focus of the piece is really the liminal state between the end of one thing and the beginning of another. The Sketchup junkyard highlights the material world but it can function as an allegory for any number of cyclical narratives. I think the idea of a Sketchup junkyard is sort of hilarious but I felt like there was more depth to it than just a clever one-liner. By framing the score in terms of death and rebirth, it provides a bit more gravity and opens the piece up to be something more. I’m not sure if the afterlife looks like a sketchup junkyard but maybe it’s a sort of psychic version of that where our spirits are stacked with others and we all decompose together and turn into something new.

Is there a particular feeling you are hoping to convey or translate through the act of navigating the audience through this environment?

It should vacillate between something beautiful and something disconcerting. I think the space we go to after death is probably very confusing with moments of intense relief, anxiety, and trepidation. I once had someone wander into the performance about ½ way through and later tell me how much they loved the visual element of the piece but the sound made them feel somewhat uneasy and it was hard to fully enjoy. That response felt really right to me.

Who or what do you cite as major influences on your creative practice?

For film I’m really into Tarkovsky; beautiful long tracking shots, weird use of color, and he’s a great manipulator of time. For music I’m really into Tim Hecker these days. The score for Katabasis was largely influenced by William Basinski’s Disintegration Loops, Miles Davis’ Dark Magus, Brian Eno’s Music for Airports and the Wolf Eyes/Black Dice split. Visually I really love Huma Bhabha’s work. She is amazing at creating these mythological figures out of really unsexy discarded materials. That work is magic.

How do you define utopia in relationship to the content of your work?

This is a great question. You should ask every artist this question. Utopia for me is something wonderful with enough of an edge to make me believe it. I recently became a parent and there is something really utopic in that; not just the smiles and beauty of it all, but the immeasurable stress and fear that comes with it too. I think that chasing some sort of pure bliss is really myopic and more destructive than anything else. So utopia becomes less about “perfect” conditions and more about an equal love for the beauty and the shit and the spaces they meet each other. I like to think my work carries some of that utopic tension.

Come see Katabasis at SPACE on Friday, April 4 at 7:30 PM.