San Francisco-based artist Jenny Odell culls second-hand imagery from internet sources (namely Google Maps, Youtube, and Craigslist) and re-presents it in collage and video form. The product of this reappropriation is “something like the most candid photo possible… we, and our world of things, are captured in an arbitrary moment by a mechanized camera on a satellite or on top of a car, or by a tourist who meant the photo to be of something else.” (See more of Jenny’s work on her website.)

Her exhibition, Long Distance, is at SPACE through June 6.

Can you talk about your history with using the web as an artistic medium?

Although it probably matters that (being in Silicon Valley with parents in the tech industry) I grew up making a lot of things on the computer, I didn’t really start using the web in my work until I was in grad school. Initially it grew out of necessity because I had just moved from Berkeley to San Francisco and was spending a lot of time on Google Maps just trying to get a handle on the space I was in. The two campuses of the San Francisco Art Institute are on opposite sides of town with lots of hills, traffic, and possible bus/bike routes in between. But it’s a short leap from using maps to look at places you’re actually going to go to places you have never been and might never go. So pretty quickly I started to see a different kind of value in mapping imagery. And once I made my first Satellite Collections piece, I realized that my set of source material was nearly unlimited. I still, when making new pieces, think of scouring Google Maps as a kind of “shopping for free.”

It seems, at least for contemporary artists working in America, that it’s getting more difficult to have the internet not affect the creative practice as a whole. Do you think that’s true? Who are other artists using the internet as a medium that you find particularly interesting or innovative?

I think that’s definitely true, because the internet is so deeply ingrained in how we get information and how we envision just about everything. I just talked to a colleague at Stanford the other day in the dance and theater department who searches Google Images for choreographic inspiration. I see it as mostly a positive thing, because it gives us access to so much information and imagery, and it can make artists out of people who wouldn’t have considered themselves creative. Most of my favorite artists using the internet as a medium are working in the “post-photographic” vein, such Jon Rafman, Joachim Schmidt, and Penelope Umbrico. Also, my very good friend Laura Kim is basically an internet chameleon with a green screen in her room that she uses to make magical videos out of anything and everything she finds online.

Describe a typical day in the studio for you.

Well, my commute is very short, since my “studio” is in the living room of my apartment. Usually I will make way too much coffee, settle in at my desk (at which, as of recently, I have a giant Cintiq pen display to cut things out on) and then realize that I have not really moved for many many hours. Both of the things I do — searching for information, and then processing that information — are absorbing to a fault. Lately I’ve been getting a little better at remembering to eat lunch at a reasonable time and to stop working when everyone else does (around 6). Sometimes for a sanity break I walk up either of the two hills I live between, which after a day of looking at Google Maps, can feel like real-life satellite view.

What kind of cultural position do you think (or hope) the internet will hold in fifteen years?

What I think and hope as far as the future of the internet are actually pretty different. I hope the Internet will continue to remain as open as it is at the moment, which I think a lot of people take for granted. I know that it falls way short of the democratic, almost anarchist expectations many people had for the Internet at the outset, but I still think it’s pretty amazing. People can still access and create so much information, find each other, and sometimes circumvent traditional media pathways. It’s been so important in allowing people — not just artists — to make meaning for themselves and others.

What I think about the internet, though, is that the current opennness, which I see as a sort of miraculous space holding out against outside pressure, will probably get closed in on. Already there have been so many legal steps in that direction, steps that are still too technical or diffuse for enough people to notice or get angry about (much like the steps taken over decades to close in on privacy — little clauses added here and there over the decades). I hope I’m wrong, but that seems to be the direction it’s headed in.

What’s next for you project-wise?

In the short term, I have three more Satellite Landscapes pieces to finish before the year is up — that project is funded by a grant from the San Francisco Arts Commission. Beyond that, I’ve been recently obsessed with gas pipelines. As part of “National Safe Digging Month,” PG&E sent out an email about safe digging practices (the time a gas pipeline exploded in San Bruno, south of San Francisco, is still fresh in everyone’s mind) and also a Google map that shows where all the pipelines are in California. I’m not sure what I’m going to do with that information yet, but for now I’ve been taking pictures next to the various warning signs (see below), many of which were in my parents’ neighborhood and which none of us had ever noticed before.

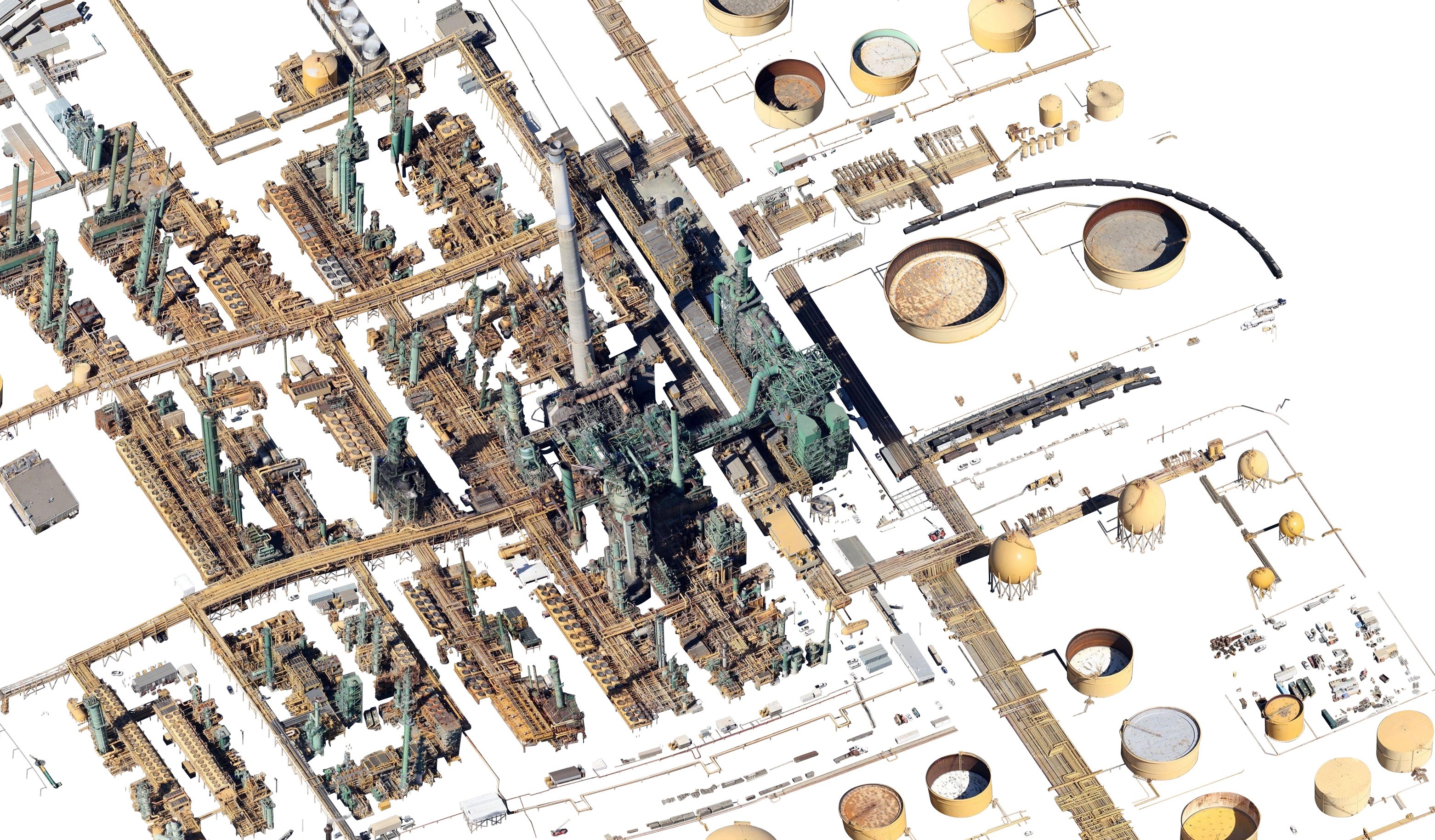

You created a powerful print and video piece, Pipe Dream, for your show at SPACE that addresses the controversial topic of the Alberta tar sands oil being transported through a South Portland pipeline. How did you get interested in this issue and can you talk about your objectives with showing this piece in Portland? How do you hope people will respond or react?

In his book Looking at Cities, Allan B. Jacobs argued that you can learn a lot about cities by just walking around and making observations, if you can use those observations as starting points for research. That’s essentially what I did, but on Google satellite view, with Portland — which I knew fairly little about at the time. I spent some time looking at it and the biggest thing that stood out to me (being a person interested in infrastructure, especially energy-related) was that there seemed to be a lot of oil drums in South Portland, but no refinery that I could find, so I wondered where it was going and where it was coming from. That question led me to the Portland-Montreal pipeline, which happened to be at the center of this huge controversy. Over here when we talk about tar sands, it’s usually in the context of Keystone XL. Many of the people over here that I’ve asked had never heard of this other proposed line; I certainly hadn’t.

It was great to be able to show Pipe Dream in Portland because the objective of my work is to invite people to re-examine their surroundings and help them get a visual grasp of something that could otherwise seem quite complicated — something that they’ve maybe lived with for a long time. My hope is that Portland viewers of Pipe Dream might then see those oil drums in South Portland in their broader context. I think sometimes it’s hard for us to square huge problems like the tar sands issue and climate change with our everyday, local experience. The piece is meant to show the oil drums, and the pipe crossings through familiar and banal places, as the place where that larger, abstract problem intersects with the everyday perspective.

When you were in Portland for your show opening and artist talk, you visited the waste water treatment plan on the East End. Can you talk about your fascination with sewage facilities?

Yes, that was one of my favorite parts of my trip! My fascination with sewage facilities started from overhead, when I cut out centrifuges for 964 Round Parts of Wastewater Treatment Plants (2013). I was working on that piece while visiting New York, and a friend and I went to the wastewater treatment plant in Greenpoint. Because there are so many steps to wastewater processing, the plants have many different, very specific, structures whose shapes I have never seen the likes of before. The Hyperion Wastewater Treatment Plant in LA is a great example of a structure that will boggle the mind. There’s something very human about wastewater plants, in that they’re basically the toilets of the city, where everyone’s waste ends up together in the end. They’re also amazing technical achievements. People forget that not that long ago, many cities just dumped raw sewage into adjacent bays or rivers. That’s why I think it’s so great that the Portland wastewater treatment plant is situated where it is, with all those friendly informative signs along the walkway — instead of hidden behind a big wall or in some place no one would ever go, as it is in most places.