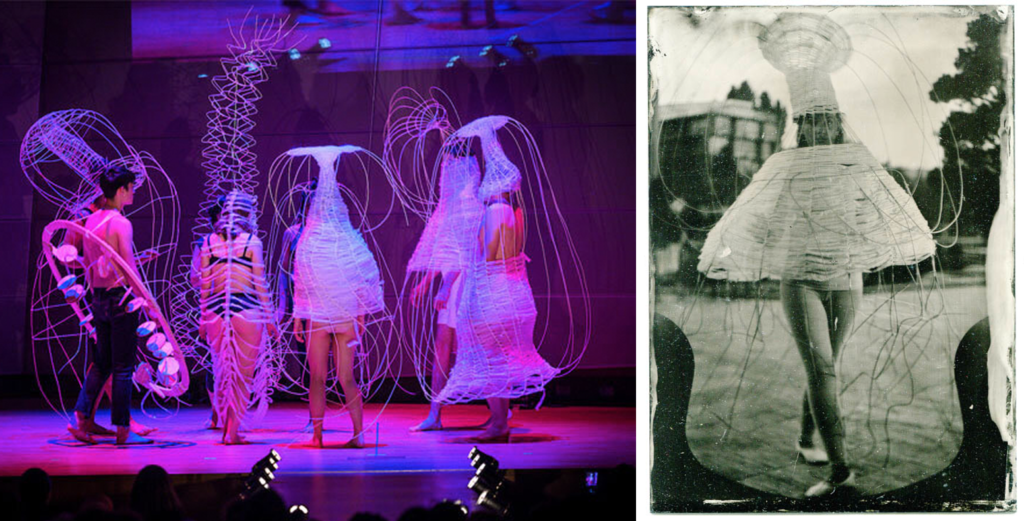

In fall 2020, interdisciplinary artist Daisy Braun sat down with SPACE to discuss her floating exhibition “D R / F T” which hung in the 534 gallery’s bay windows in Portland, Maine for the month of September. The conversation bounced on several subjects including symbols of deep time, alternative collaborations, climate crisis, adapting artistic practices in the pandemic, and more.

Your work seems to meet at the nexus of art and science. I don’t know many artists who make work about plankton–a subject over a billion-years-old! What sparked your interest in “Deep Time” and whole system thinking?

I wanted more context for the things in my life, and I ended up taking it to the extreme. In college, I was interested in situations where time was “compressed,” or where the past and present could exist together. This could happen in the life of an object across time, through tradition or myth, or in the regeneration of life across generations–just to name a few! I started fixating on “constants” through history, meaning things that have been, are, and will be present through the full scope of life. It felt natural to start with water: the birthplace of all life on earth. This is how I got on track with plankton. A constant. Necessary to life. Their ties with the climate crisis created added urgency for me, too.

I approached the theme of ‘time’ from many angles. While I was working on the plankton sculptures, I was writing a thesis paper about the 2004 Athens Olympic Games and its relationship to historical “compression”, and another thesis paper on nuclear waste warning messages (communication meant to survive 10,000 years or more, to protect future humans from the radioactive mess we are creating on earth in the present day). So that was another way of thinking far into the future–how artists could represent a danger symbol to mark places that people should stay away from.

A symbol– abstract iconography that transcends dialects and time?

Yeah, for sure. I was thinking a lot about symbols that could transcend time, the power of images. When I was writing the thesis about the nuclear warning messages, I also had a section on the Pioneer Plaques that Carl Sagan and his wife Linda Salzman did. It’s a little golden plate that has a very simple line drawing of a man and a woman and I think the structure for hydrogen or something. It has some basic stuff but that was very controversial, like what should we be sending into space? Will aliens be able to tell what these images are, will they understand perspective? There was also another section [in my thesis paper] about the World Seed Bank, because they’re saving seeds for the future to keep life going. Plankton to me is so important but it’s only one piece of a puzzle that I was putting together. When I thought about plankton as a type of symbol, and once I learned more about their specific relationship to climate change, it kind of went off in a new direction.

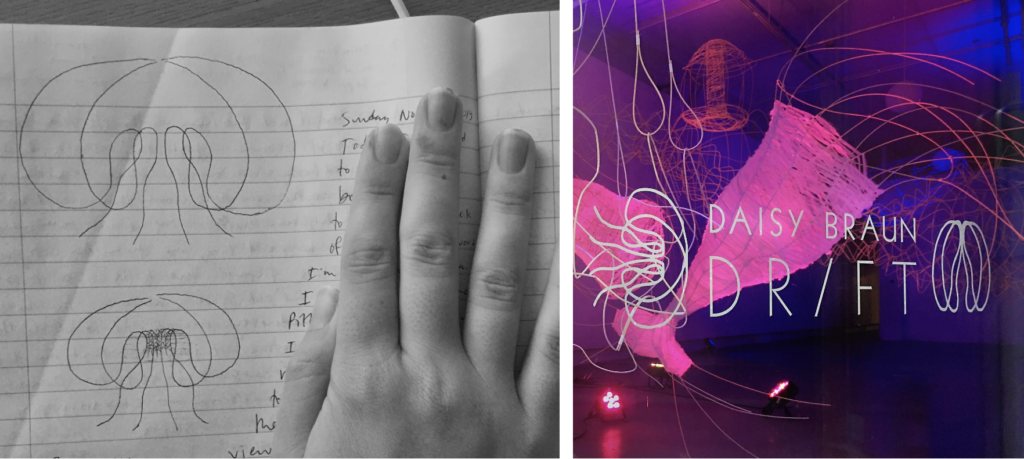

You shared a variety of line drawings from your sketchbook that looked almost like hieroglyphs. Not only was there symmetry that you would see in a lot of icons, but your lines implied 3D space on a flat surface. I love how your work can go from very small sketch studies to an incredibly large scale. How did you get interested in putting a magnifying glass on plankton?

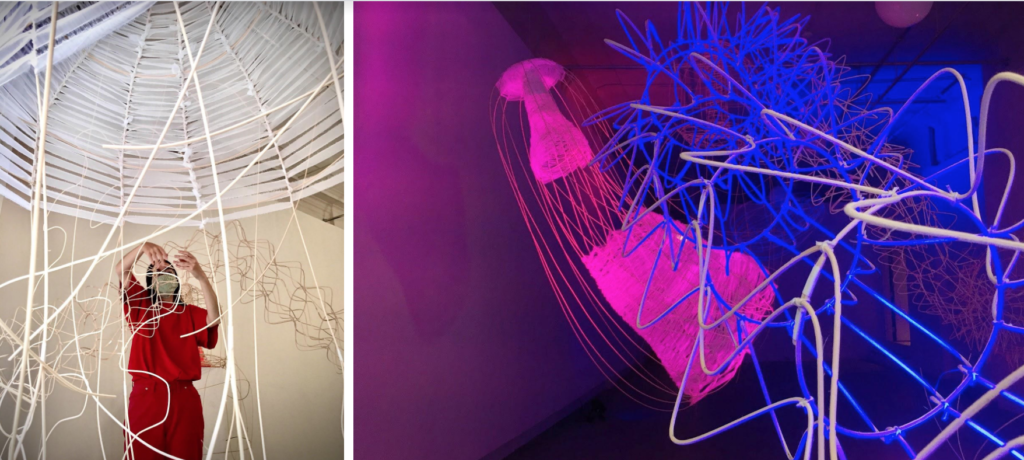

That’s a good question. I love microscopes and being able to expand your vision of things that are usually invisible. At the time I was also really interested in kinetic sculpture, which is quite difficult. I was trying to make mechanisms and things that would move on their own and it felt easier and more fun to just put them on a person and have the person have control of the movement. As far as the connection between plankton and people and all life on earth, it made sense to have them be at human scale.

I love seeing the symbiosis of plankton and the human body in your art. Originally, you were slated to share this work as a fashion show in April 2020 at the opening of the traveling exhibition, Punctures: Textiles in Digital Material and Time. The work would have been presented to a live audience, with these plankton-inspired sculptures scaffolded on human bodies, moving in and out of the crowd. Due to the pandemic, it’s taken on a very different approach: the work is now stationary and peeking out on downtown Congress Street. How did this shift in presentation change your understanding of the artwork?

When I began this body of work about plankton in 2018, I made everything wearable. Without a person, the pieces were incomplete. I felt that performers gave energy and movement to the forms. Performers also brought the work out of my control, which I think was healthy. I have thoughts about choreography and movement, but performers usually do too, and it’s good to listen to them. They get to know the pieces quite well, usually in a different way than I do.

Right: A plankton performer poses. Wet plate collodion photo by Dino Rekanović and Torsten Wieczorek.

That being said, with the absence of people in this show, I spent more time thinking about composition, and light and shadow. I also thought about the plankton silently floating in the Gulf of Maine, and my fabrications floating on Congress Street. This show has a different atmosphere–quieter, despite the bright colors–but maybe that trends with the times. Environmentally, things are dire. Maybe it’s more realistic that we aren’t embodying plankton right now.

The exhibition reads to me as a freeze frame, you’ve got these images suspended and it is kind of like a ghost note pause in time.

I like the word freeze frame, because even though it’s static I was hoping that it would convey a lot of movement with the way the pieces are swirling together, almost as if it’s a little drop of water, but huge.

The way the exhibition is lit, with the help from Sean Mewshaw, brings another dimension to the work–especially at night.

I think the lighting totally changed the whole atmosphere. You and I installed the show together and we just had the fluorescent white lights on overhead, and I feel like the work just camouflaged into the walls. It made me nervous because I was like, ‘these really don’t look that intense right now,’ but then once Sean came in and we were working on the lighting, they just lit up from the inside. I think that really changed everything.

Yes, the lighting made natural reed radiate a neon glow. But it’s not just theatrics to grab people’s attention, it also reflects back to nature where plankton in certain conditions are bioluminescent. It can be subtle–you have to know when and how to look for it–say move a paddle in the water at night to see it emerge. I feel like your work is similar to nature in that way. When you walk by Congress Street at lunch it’s going to look very different than if you walk by at 9pm.

Definitely. [Regarding] light and plankton being luminescent, Morten Strøksnes, author of Shark Drunk: The Art of Catching a Large Shark from a Tiny Rubber Dinghy in a Big Ocean, talks about how deep underwater animals and fish communicate with light. He said that the language of light is the oldest language in the world. And immediately I was like ‘ooh that’s up my alley’–going back to languages that can stand the test of time, or symbols. I love that it took the human-centricity out of it.

One of the things you wrote in your artist statement was how politicized climate change is. A theme you mentioned earlier with nuclear waste sites that [ties in is] sadly it seems like affordable housing tends to get built on these contaminated sites. Soil samples are sometimes lied about, and community gardens are unknowingly built on potentially toxic land…

Exactly. That was the conclusion that I came to. I went into that project being really interested in the design of the long term warnings and thinking ‘ooh I’m an art student, I’ll come up with my version of conveying info to people in the future’ and the more I learned about it, in the ’80’s and ’90’s the government had a task force of different interdisciplinary people who were supposed to be doing that job. But even then, people were not being protected from the nuclear waste that was being made at the time, and that’s true now. Hazardous waste is more likely to end up in poorer towns, especially where the majority of the population is Black.

You grew up on Peaks Island off the coast of Maine–how do you think that shaped your perspective?

The community I grew up in was very present. Everyone knew each other–little kids, old people, whoever. We had potlucks, we borrowed each other’s stuff, we gave each other rides to the ferry. I think that feeling of love and interconnectedness easily translated into how I viewed–and valued–the ecological relationships around me. Seaweed, periwinkles, crabs, birds, trees, deer… All the other creatures inhabiting the island relied on each other too. I grew up with a lot of wonder and reverence for the natural world, because it was so visible to me. Ecosystems carried a lot of weight. The ferry would only stop due to high winds and tall waves, never someone’s schedule. More recently, it stopped for the virus.

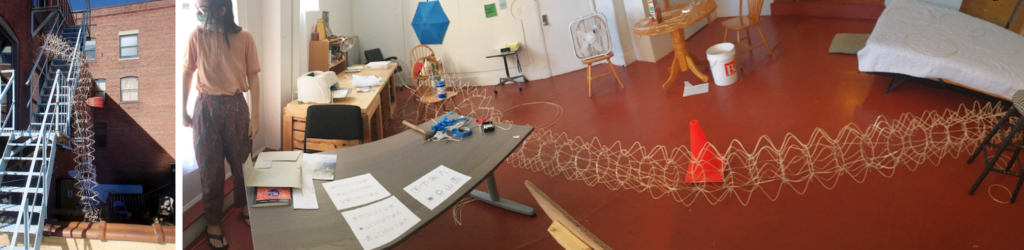

You were artist-in-residence at SPACE for three weeks leading up to your exhibition. What was that experience like for you? It’s not lost on any of us that this was also during the COVID-19 pandemic…

It was different for me! This was my first time occupying a studio by myself. I’m used to sharing a space with a studiomate, usually with several more studios in close proximity (think: art school). This is the biggest studio I’ve used. With more space to spread out, I made much larger work. The long zigzaggy piece got too big for the studio, so I ended up bringing it out on the roof, and jerryrigging it to the fire escape with tape and a broom. That piece ended up being about 18 feet long.

My experience in the studio was more solitary than I’m used to. I really enjoyed being down the hall from Pickwick Press, but for the most part I was alone. I listened to hours and hours of podcasts, RadioLab, mostly about biology, or the virus, or more narrative storytelling stuff. Hours of music, too. I sang a lot. Not sure if anyone could hear me?

I’m curious how you came to weaving these large sculptures. Did you do case studies at a smaller scale originally? Did you do any basket making growing up?

No, I don’t have any experience weaving. It started with ideas for making big plankton sculptures, but I didn’t know what materials to use. I made several that completely flopped, out of other materials. I made some out of wood that were really heavy and got people to wear them, they were like ‘this is not comfortable, this isn’t fun’. Not only is it not good for the person that’s wearing it, but it doesn’t look light, and I think plankton have a lightness to them. I tried some from just fabric but I didn’t really have any structure to it, and it took forever because I was trying to make my own patterns. So there was a good four months of making things that didn’t work. I was getting really stressed because I was doing it for a show and they were like ‘you need to have something to show for yourself’. I started to think about what I could use for armature that could be light, and I happened to walk by a class that was bending reed for basket making. It just jumped out at me, and I was like ‘that’s what I need to do’, and I learned how to do it by myself in my studio.

You landed on an ideal medium for creating an exoskeleton out of reed and then weaving between the negative space with silk.

Thank you. To say more about the materials, I felt like I couldn’t make a body of work that was trying to say ‘the earth is so important’ and then make it out of materials that can just be trash. It was important that reed is a natural material.

Where do you see your practice going next?

Of course I keep coming up with projects that would involve gathering people together, but I try to sketch them out and move on. I’ve been using this time for research, exploration, connecting the dots… the background stuff. Drawing and painting a little too.

I definitely have a lot of plans for after things are safe. In this time I’ve been thinking more about collaborating–that’s really exciting to me. I’d like to do more in that direction, I think right now is a good time to reach out to people. And not just scientists, other artists.

I could see your work in an opera about climate change or a theatre setting…

Yes! Oh my god, theatre, that’s really where I want to go next. Doing a larger scale performance. The fashion show was really fun and I love how that turned out, but it wasn’t really on my terms, it was through their production, and I had maybe five minutes I had to stick to. It was in their space on their terms. I would love to do something longer with more performers and more of a set and more time to explore lighting and music. That could really just go off in so many directions.

I think the thing I like about performance is that it tends to not be an isolated thing where only artists and people who care about art show up. In my experience it’s been a lot of families and local people who are interested. I really like that, that’s what I like about showing it in the SPACE window– anyone can see it, not just people who would be inclined to go to a gallery.

Click here to read Braun’s artist statement and revisit the exhibition. To view more of Braun’s work or get in touch about projects, visit www.daisybraun.com or follow on Instagram @daisy___braun .