I spoke with Asata Radcliffe on January 9th, shortly before SPACE announced the 15 recipients of 2020 Kindling Fund grants. Her winning project proposal for “The Black Guards Living Installation” will be a historic boxcar set with a replicated representation of the lives of Black army soldiers stationed along the railways of Maine during WWII.

We spoke about the phases of the project, her experience navigating historical research as a woman of color in Maine, and the healing and visionary potential of futurism, speculative reimagining, and nonlinear histories.

You have shared that you first learned about the Black Guards of Maine through an essay you found in the Monson Historical Society while in residency at Monson Arts. Can you tell me more about how your research unfolded from there and how that sparked the beginning of this project?

It was my first artist residency and I was also the first artist the Monson Arts residency ever had. When I am traveling throughout Maine, I am always wondering who are the Indigenous people in this area. I wasn’t looking for anything about the Black Guards. I went into the Monson Historical Society looking for Indigenous history and I stumbled upon this short essay by Bill Sawtelle.

When my time at the residency was over, a lot of people wanted to know how my experience was. Especially because it was a new residency, Maine is a small place, and a lot of folks in the artist community wanted to know what it was like for me. So I started talking about the research I had started. And whenever I talked about the Black Guards, people wanted to know more.

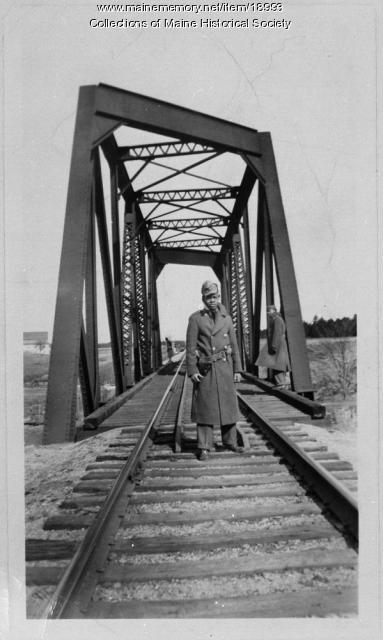

I spoke with Jenna Crowder, who is the editor of The Chart, about my experience in Monson and she suggested I write about it. I started going through more archives at the Maine Historical Society and found a couple of photographs there, but just a few. There was some informal interviews that had been done in 1999 for The Forecaster about the Atkins family in North Yarmouth whose grandparents had remembered the Black Guards.

I decided to take a second trip back to Monson and go back on my own. That was a whirlwind Labor Day weekend. I interviewed an elder, Bob Roberts, who is now deceased and he shared this big photo album with pictures of the Black Guards that had never been shared with anyone before. I interviewed him and he offered to give it to me to scan and digitize. Myself and Monson Historical Society staff member, Elaine Roberts, spent hours scanning the photographs. The people at the Historical Society were telling me that I was meant to tell this story. It gives me chills.

It seems clear that there is no real comprehensive record of the Black Guards that exists yet. There is a real hole in the written history that you are identifying.

Yes. I am not from Maine. Being a person of color from away, you don’t encounter any histories of people of color or Indigenous histories of Maine easily. You have to look for it and dig for it hard. The fascination that began with this project was a personal fascination that turned into me recognizing that more people want to know more. This is something I stumbled upon for a reason. I started thinking that maybe this is something I need to put more energy into. Once that sunk in, then I began to feel obligated to do it.

I can imagine there would be a great sense of responsibility that comes with a project like this.

There is a responsibility I feel now to unearth this history. I think it will be good for me. I think it will be an educational experience, because as I read about the history of people of color in Maine and particularly Black people, you really see that it was never meant for Black people to live in Maine.There are some Black families that have been living in Maine for generations, but when you look back at Abolition times, you see that Maine is white for a reason. I can give you a long list of reasons as to why Maine is white. It is intentional. Black people were coming through here as transitory people. People were not striving to make a space for them or to include them in the community. Black people were moving through Maine during Abolition, on their way to Nova Scotia.

As I look at these men who were deployed to guard the railways of Maine, they lived in a boxcar. They didn’t have housing. We know how Maine winters are. This is another example of how we treat our soldiers. Their presence here was transitory. So far, I haven’t come across any information that pointed to anyone taking steps to make a permanent home for them.

You know, there were some people in towns who were nice to them- the wife would make a pie and the husband would walk it over. But they had to go into town just to get water, they had no bathrooms. I cannot imagine how it was for them.

Having to protect a community but never being welcomed into it.

Exactly. That is the irony of it. Having to protect your country but not being allowed to be a full and free citizen of it. When I look at how racism plays out today in white liberal Maine, a lot of it has to do with that apathy. On the surface there is a perception of Portland being so progressive, but when you look at where the Black and immigrant people are living, you see it is a segregated town. When the KKK showed up in Freeport when I was living there in 2017, people asked me, “Have you ever thought about moving”, or “Maybe you should move”. This is what was being said to me. They weren’t asking “How can we make this a safer community?” They think they are absolved from that. If you believe in dismantling racism, then we are supposed to be co-creating this inclusion together.

In terms of the Black Guards, those are the questions that are unanswered right now as to what they were experiencing with the communities they were placed in. But clearly there was no effort made to help them find real housing.

You have an exhibition at the Maine Historical Society coming up for the Maine Bicentennial, which will include historical images and objects from the Black Guards. Can you talk about how and why you wanted to develop a 2nd phase for the project with the boxcar installation, and how that might operate differently than a more traditional exhibition?

Installation in general is new to me, Monson was the first time I really started experimenting with creating an installation in my studio. I asked myself why I am drawn to this, but you know I am a filmmaker. That is in my background and I like staging things to tell stories. That just feels natural to me.

I am going to create the story of the Black Guards in an installation at the Maine Historical Society, but it will not be traditional historical presentation. Doing that is like the first act. The second act is the boxcar.

An artist who is an inspiration for me is Doris Salcedo. She is from Bogota, Columbia and she does installation work. The narrative of her life and what she does in the public space is just astounding. I aspire to be like her when I am older. I have to mention her, because looking at the scale of her work gave me the confidence to go with the boxcar idea. I want to do things on that scale. When you really create an immersive environment like a living installation, its transforms people, more than just reading history or looking at pictures in a museum. To be able to let a viewer feel and sit with history is important. We shouldn’t be able to brush it off so easily.

This cyclical experience of racism and white supremacy is going to continue to play itself out until we reconcile it. I don’t think we are going to reconcile it with diversity training. I think art is going to be part of what transforms it. I want to contribute to that effort and I want this project to help with that. Doris Salcedo did that in talking about white supremacy and racism in Bogota. When you have someone who has done it, it stretches the limits of what is possible. You start to think big.

On your website, you describe some of your primary research interests as being land rights, futurism, and nonlinear histories of human existence. Does your historical investigation and replication of the Black Guards of Maine have futurist implications? How does correcting historical erasures change our vision for the future?

It is interesting that you phrase it that way. I don’t see the project as corrective. All of my work is speculative. I am reimagining this story.

In many futurist works now, the common theme is dystopian. I am trying to reimagine a different future than that. I am not saying that we are not going through dystopian times, but we are going in a new direction in Maine. We have so many new immigrants here, and I can imagine things are going to get a lot more colorful. I think Indigenous people are going to begin to reclaim more of their spaces here. That is what I want to show. Bringing that history into the future. That is all I can say about that right now. I have never done a historical work like this before and merging that with futurism. That is part of the quest of this project. It is really exciting as an artist to not know what is coming next as I move through this.

The scope of it is what keeps me sane. I think we have to be visionaries. I think being a visionary is a healing practice. If we were just to settle with watching impeachment hearings it would be a really coarse existence. The futurist path has always been about imagining and being a visionary in the process of reconciling the past and present.

You have mentioned that you, like the Black Guards, are also “from away”. Can you share some of the things that reverberated for you from what you have learned about their experience so far?

Yes. I have been thinking about that. Why am I drawn to this history? Why am I drawn to these soldiers? I think just being a person from away, and being a person of color from away, living in Maine. The isolation that I felt moving here and going through my first winter here was intense. I was living in Freeport at that time and I had never experienced being snowed in and that lack of freedom of movement. I am from California. I started thinking, what is it like for them–the Black Guards? What do they do being out on the tracks when the snow storm blows in? There is nowhere for them to go.

That was another connection I made. These are Black men, they have to be very cautious when they need to go into town. Those are some of the things that I am experiencing still and I talk to other people of color from other cultural communities and I hear that they are experiencing the same thing too, so I know it’s not an anomaly. If it’s not an anomaly now it would have been even worse for them in the 1940s.

Then, what is even more horrific, is that a lot of these men had to go back home to segregation in the south or to the small towns where they came from. Lynching was a common practice then. It was so dire- they are trapped in a boxcar and then what do they have to go back to? I wonder if some of these men joined the military to escape those conditions. To try for some respite. But then here they are in Maine in a boxcar. Isolated, but still having to be of service.

I understand that this is a history that needs to be for all of us. But there are some real and deep personal connections for me.

A project of this nature involves extensive collaboration across racial lines, just for you to be able to get the research you need. You shared in your Kindling Fund application that you welcome and invite that collaboration. What has your experience been so far negotiating the research process as a Black artist in a primarily white state?

I was really afraid to go to Monson for the residency. I was still pretty new to Maine. Going to a one month residency was a big deal. I got out there and there were Trump signs around, one right across from the house I was staying at. At the time, the studio space was a long walk away and you had to walk through town. Here I am this Black person walking through town and there are people on their porches just watching. They had never had artists up there. It was all new.

But once I stepped into the Monson Historical Society and I stumbled upon Sawtelle’s essay, it was like all this love broke out. The folks who work there are the elders of their community. And everyday they were asking me when I was coming back. They would come by my studio looking for me when they found some old article in the archive about the Black Guards. They were so supportive.

They came out for open studio day and saw the installation I did with all the pictures and research I had found, and it was shocking how many people were in my studio crowded around the Black Guards materials. There were a lot of older men, mostly in their 70s, and they are talking about this time period. It would have been their parents. I had to leave because there were so many people in my studio and I was overwhelmed by the emotion that was coming out. That was really wonderful. This is an all white community that is really supportive of my research, and were truly my cheerleaders while I was there.

Also, working with Tilly Laskey at the Maine Historical Society has been incredible. She is doing a Bicentennial experience, “State of Mind: Becoming Maine” with Wabanaki and African American histories being told in Maine. My installation opens within that exhibit, May 1, 2020. She gets it. There are certain people who are white who get it. That show is striving to see Maine from a clear perspective and not just a crafted narrative of what we are used to seeing. There is so much we all need to learn about the people who were here before everyone else, the Indigenous people of Maine. I am working hard to tell the story of the Black Guards in alignment with the other storytellers in the exhibition. I am so thankful that I was asked to be a part of it.

I am hoping that having this boxcar to be a way for people to not just engage with this story, but also have conversations with people in the space. I want people from Monson or other places all over the state from where the Black Guards were, to come and share their stories. Maybe they would share their stories in the boxcar and people would listen.

Is there anything else you would like people to know about the project at this stage?

I am looking to purchase a boxcar- that is my big goal right now. I don’t want a really nice revamped one. I want one of the wooden ones of that period. If there is anyone who is in the railroad community who is interested in partnering with me on this project I urge them to get in touch.

I think it is important for people to know that it is not easy to navigate this as a woman of color approaching old Mainers who don’t know me. I was able to do it in Monson so I am hopeful, but when you are a person of color and you are trying to tell these histories, you have to enter a lot of spaces where folks are just not used to engaging with someone like me. It is not just being a person of color, it is being from “away”. People joke about it, but it is really deeply entrenched in the culture of Maine and it is very isolating. It makes it more difficult to negotiate, especially for people who want to make this their home and who want to create here and do innovative things.

Going back to Doris Salcedo, her work spoke to all of the drug crime that was going on at that time in Columbia. She talked about all of it. I can imagine that was not an easy thing, and a potentially dangerous thing to tell those stories. Artists of color have to contend with these things. I am learning this new here, living in Maine. I wish there was a guidebook as to how to navigate these situations to get the work done.

I also just want to thank the Kindling Fund and the judges for appreciating the project and all the people here at SPACE.I have just been in my solo space working on it and researching it as a labor of love initially, not as an art project. There was never an intention to create work around the Black Guards. I was simply compelled to learn more about them, and now that I am creating work around this history, it is amazing to have it so well received.

It is all about these men who were here guarding Maine. They deserve to have that service and history highlighted and treated with respect. This is a historical piece and I am a futurist, but with this work I am trying to create a relationship with it where I know that this is something for the public. It is mine now, but when I release it, it will belong to everyone else. It is just about shifting your relationship with what you are working on and realizing this is about public engagement.

Top image credit: A rendering of Asata Radcliffe’s “Black Guards Living Installation” by Asata Radcliffe, Trey Jones III & Sunny Lamb.