First I just want to thank you for taking the time to answer these questions. I was very moved by your film Malni- Towards the Ocean, Towards the Shore, and wanted the chance to talk to you a bit more about your process as a filmmaker filmmaker, as an Indigenous artist, and as a person working outside the realms of conventional storytelling in cinema.

I’m really struck in Malni, at how the environment takes on its own voice in the film. In some ways it’s what binds the elements of narrative- from Jordan, to Sweetwater, to the narrator- we are all placed in a specific tonal location. I’m wondering if you could talk a little about how nature plays a role in creating your work- and how or if it stands as a character in this film in particular.

Malni is at once a very intimate film and also a very elusive one and It’s really exciting how you strike that balance. We are aware of your voice as a filmmaker, your relationship to the main subjects, and your literal voice as a narrator and interviewer in the film but you are never introduced or shown on camera. How do you decide to partake in the films you create- or how do you know how much of yourself to insert into the films?

I think my participation comes pretty naturally, as it’s a mode I’m comfortable working in. I try not to be too visually present, or aurally present, but when I do I hope that it functions as a way where I as the filmmaker am guiding the audience through these different spaces and these relationships. With this film in particular, I want to give Jordan and Sweetwater as much space as I can for them to tell their own stories, and my role then becomes one in which I convey how I interpret these stories and even how subjective that interpretation is. I ended up cutting out about a third of my narration because I didn’t think that it was necessary, or that those movements and gestures and voicings by Jordan and Sweetwater did enough and didn’t need me adding anything else.

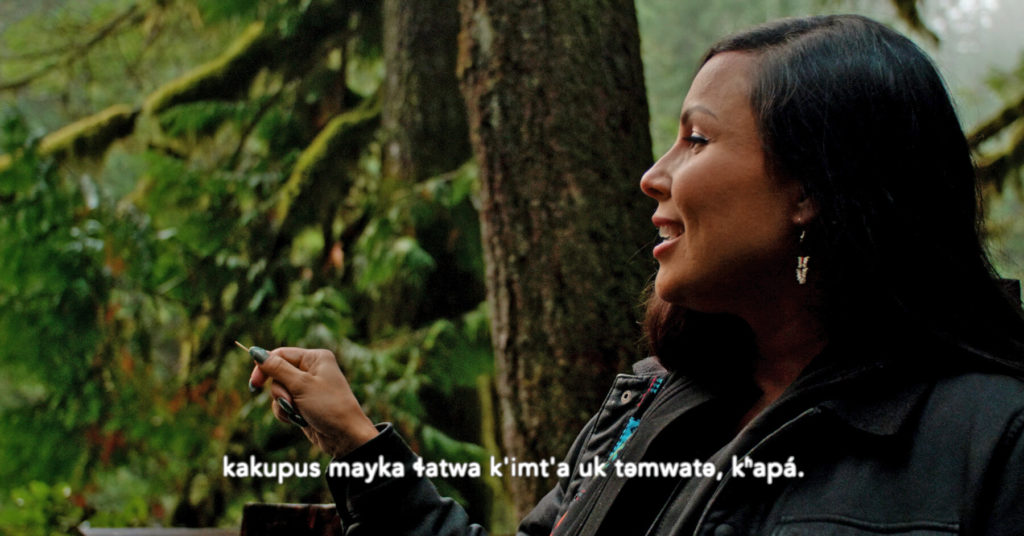

Language is a huge element of what is going on in Malni. Can you talk a bit about shooting the film in Chinook Wawa language? I loved that you translated the English speaking into Chinook Wawa as well and it made me think more about the audience in a way– who is watching the film, who is the film for, and who are other films shutting out?

I knew I wanted the film to be in chinuk wawa since before I started the treatment, it was just something that made sense and a place that I wanted to visit again. Jordan and I speak chinuk fluently so that was pretty easy, and our conversations are pretty much like what is seen in the film so that worked out pretty well. When Sweetwater came to the project, it was early on in the camera test phase of the film, that I started to think about other ways to present the language other than as spoken. She doesn’t speak the language, and I didn’t want that to be a barrier to her participation in the film so the simple and elegant solution was to subtitle them both with similar treatments. Language became a means to conveying their stories and their voices, and I wanted to do little as little as I could to get in their way.

Do you feel that there is a conventional language of cinema that you are subverting? Do you define yourself as an experimental filmmaker?

I wouldn’t say I’m subverting it, as that’s implying that what I’m doing is focused on those conventions. Rather, I feel like I’m treating those conventions as tools that can be applied in different ways that are appropriate for the cultures and communities that I’m coming from. I would say I’m an experimental filmmaker, and that’s also a term that can get swallowed by semantics and different approaches to the form, but for the reasons that I said before I feel that the cinematic tools at our disposal are ripe for experimentation and application beyond what we know or have been taught.

There is something very languid and almost transcendental about the film. The sound design in particular sets a really unique almost out of body tone right away. I also loved about an hour into the film that the images go completely, deliberately out of focus and there is this amazing pan shot. The viewer in that moment becomes extremely aware of the colors in a way that an in focus image couldn’t produce. Can you talk a little about that decision, and also the way you utilize sound design?

I was playing around with the foreground and background all through that scene, as Jordan and I were on a mile hike to that waterfall and I was following him. There was something simple about focusing on the background that emphasized some of the things I had been thinking about while making this film that reflected nature, legibility, and visibility that just made sense. So when we got to the waterfall I had already been thinking about the unfocused image and the blend of the bokeh from the lens I was using. Simply put, Jordan went to go pray and I didn’t want to film that, because it wasn’t for me to film and it certainly wouldn’t be for an audience to watch, so I unfocused the image and started turning. There’s significance in those turns I won’t get into, but it was just a series of movements and gestures that felt right.

In regards to the sound, it’s one of the framing tools that I use for building out the film. The music was a strong unifying tool in the editing of the project, and as I was working on editing out these scenes the sound design really became a space for me to abstract them in a way other than visually. I tend to do a lot of visual abstractions in my short films, and I didn’t want to do so much of that with this film and that gave me an opportunity to think about the sound as an abstracted space with somewhat straight visuals, a lighter touch to embrace myth without distorting the image.

There is a lot of discussion, especially with Sweetwater about breaking cycles both generationally and personally for her. The film overall contemplates future generations in a really beautiful way. I love the power that Jordan and Sweetwater give to the unknown in that sense. There is some sort of strength generational restoration, but also in starting anew. I’m wondering how you see the cycles that Jordan and Sweetwater discuss in the film, and how youth or future generations are able to either break or restore those cycles?

I see them as uneven, overlapping, misshapen spirals, and that’s a small difference but an important one. They both offer their thoughts about breaking cycles and maintaining tradition–two ideas that aren’t at odds but hard to describe. I think that they’re both, we all are actually, in this space of looking to our pasts and histories for strength and hope, and also trying to make things easier and better and healthier for our future generations by letting go of those things that have been harmful and painful, but still trying to figure out which is which. There’s no easy answer, and perhaps the thing that ties Sweetwater, Jordan and myself together is that we’re all trying our best.