Dan Hawkins was born in Cumberland, Maine (1990), has worked as an architect in China, Denmark, and the United States and as a carpenter in the United States; and holds a Masters of Art from the Royal College of Art in London (2019). His work has been shown at the Danish Architecture Center (Copenhagen, 2013), London Design Festival (London, 2018) and the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism (Seoul, 2019). Dan walked the length of the United States in 2014 (2,000 miles, 5 months) and the length of New Zealand in 2017 (1,800 miles, 4 months). Always in pursuit of a creative side project or that mountain on the horizon.

What is the current status of Ghost Line, and how has COVID interrupted it?

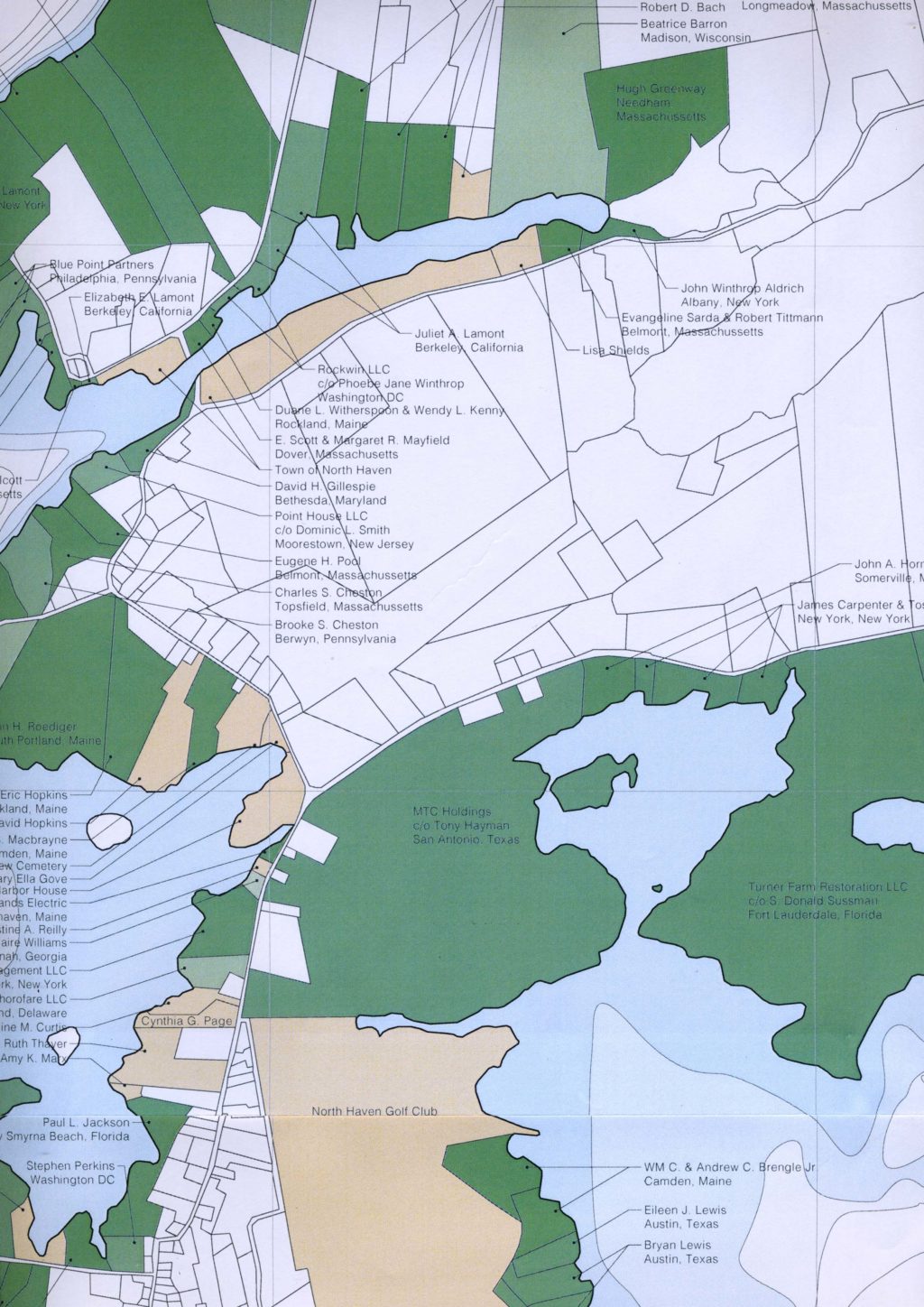

The initial attempted scope of the project was to map every single coastal property in the state of Maine, then produce a physical map and bring printed maps to each town. In the beginning of 2020, before COVID, I didn’t get some other grants and fellowships that I had applied for so that was a stumbling block for the amount of time that I felt like I could give to the project. The building up of the project involved a ton of sifting through tax maps and commitment lists and collating that information, and what I was most excited to do was to bring the finished maps to the towns and have people respond to them, so it felt like that wasn’t going to be possible in 2020 for sure.

There are a lot of second homes in Maine, it has the highest percentage of any state. With COVID came a lot of people from out of state who owned homes in Maine, feeling like it was safer to be in Maine. You may have seen the news about residents on Vinalhaven felling trees in a driveway as people from out of state were coming to the island during the pandemic. It really seemed like a scary form of frontier vigilante justice.

So I think that caused a lot of tension, specifically in the case of Vinalhaven, between locals and non-locals, year-round and seasonal people. It felt like, that’s just going to keep growing, so it feels important to keep pushing the project, even if it’s just producing maps. I think because I didn’t get other grant money, I was so stressed out about everything I couldn’t look at tax maps. I work as a carpenter and jobs were falling through and coming back all through last summer, so we were never sure if we were going to be bankrupt or not. The winter has felt hopeful, and what better way to spend dark nights than to pour over commitment lists?

One of the things I have always struggled with in this project is it’s really easy to inadvertently make this project about an ‘us and them’ situation, and that’s not what I’m hoping to achieve. I’m hoping that putting the maps in the communities could add as a layer to the project. Looking at a map of North Haven it’s like ‘holy shit, there’s a lot of out of state residents here’. The knee-jerk reaction is ‘why can’t more Mainers live there’? So it felt like the Vinalhaven incident fueled that. In October the Press Herald released a summary of September housing sales, it reported homes being sold to people coming from out of state has increased to one in three. That’s been a really tricky thing to navigate, where does Ghost Line position itself? Is it making a statement that it’s a good thing that people from out of state are moving in?

Moving forward with this project, have the events of 2020 (COVID, social, political) made you rethink the original concept of the project at all?

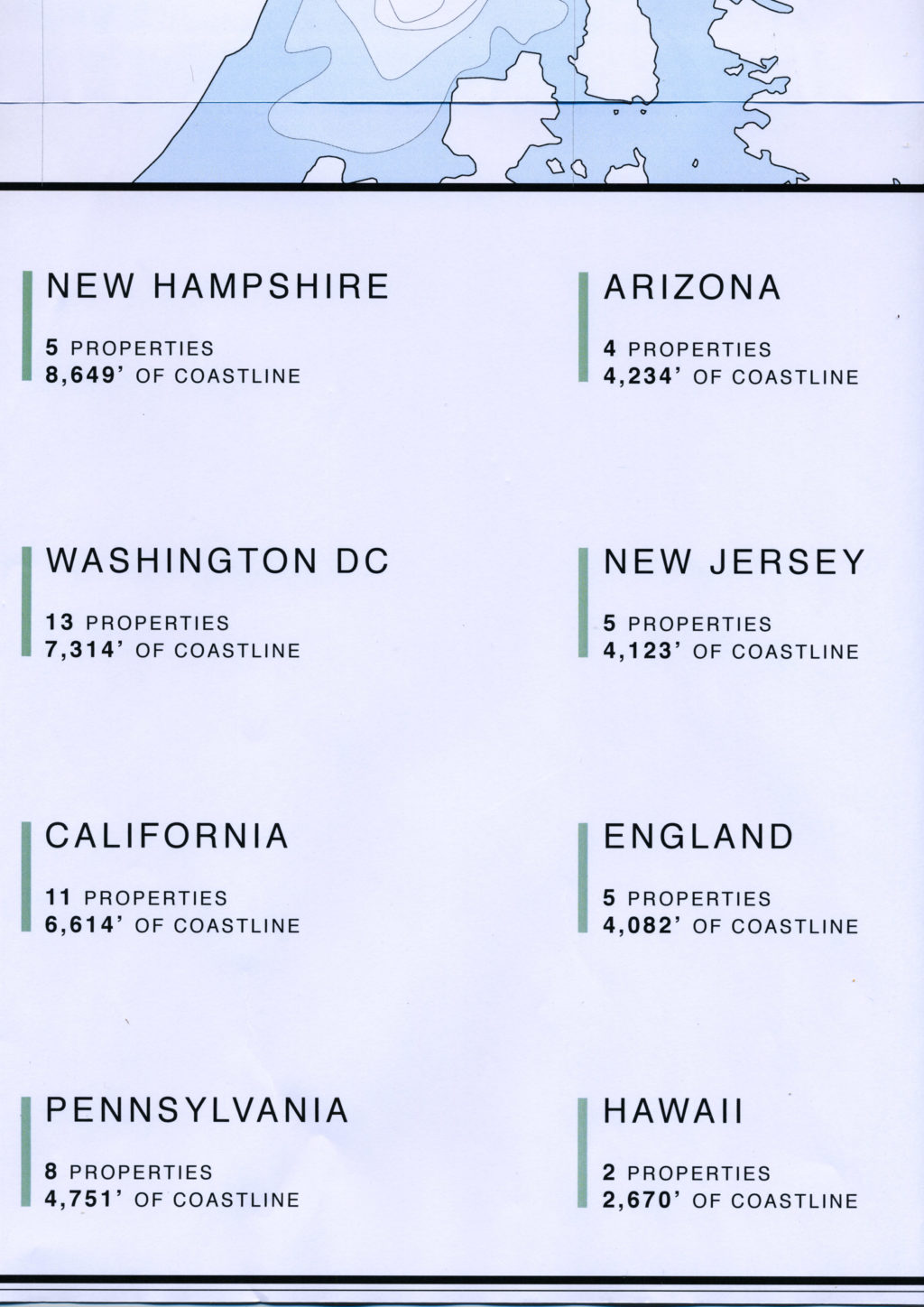

I’ve scaled down the scope, and I’m focusing on islands. There are 15 unbridged island communities in Maine, and I’m hoping to start with mapping all of those. I think those are areas where the dynamics are maybe most tense. Also they might be good canary-in-the-coal-mine indicators to the community tensions on the mainland. In terms of the community engagement part of it, I’m talking a little bit with the Island Institute and organizations like that and trying to publish the maps. In the case of North Haven, I know a couple people on the island who I’ve met through other projects so I’m just going to send the finished map to anyone who would like to see it, and hopefully that can stand in for now. It already feels like a very monastic project, because I’m just sitting and looking at documents, it’s an exhausting and never-ending claustrophobic cubicle of research that I find myself in. I thought it may be fun to try and print it as a newspaper insert or something like that and see if I could attempt to just disseminate it in some way. There’s a lot of hours that are going into the project, but I’m hoping to use the grant funding for a printing, or a distribution. I feel like if there’s any value to the project it’s there, not in me sitting by myself doing the research.

What are those 15 island communities?

There are 15 unbridged island communities, not all of which are autonomous. I’m going to map all 15, regardless of whether they are part of a mainland town or not. These are Cliff, Peaks, Great Diamond, Long Island, and Chebeague in Casco Bay; Vinalhaven, North Haven, Islesboro, Isle Au Haut, Monhegan, and Matinicus in Penobscot Bay; and Swan’s, Frenchboro, Great Cranberry, and Islesford in Down East Maine.

You mentioned wanting to err away from the concept of ‘us versus them’, what is your process navigating out of that mindset?

A couple years ago I did a project about lobster fishery in Maine, I was able to connect with a couple of different boat captains along the coast. One of the things I was really interested in with that project was the informal fishing territories that are regulated by each discreet community. We would have conversations about where they fished, and how, and what they were fishing. I would bring a blank nautical chart and they would notate over it. The captains would notate different species of fish, areas that were hard bottom or soft bottom. My vision for Ghost Line was that I could bring the blank property map and have people notate ‘oh this is where I walk’ or whatever. I have spoken with some people from Vinalhaven and North Haven who have said “there’s a fair amount of trespassing that occurs in the off season, and simultaneously there’s a fair amount of good faith acknowledgement of ‘oh yeah I’m not there but feel free to use that’”. So hopefully I could have those notating events in the summertime when the island populations are full, so that seasonal and year round people can mark up how they use the coast regardless of who owns it. So that is one way I am hoping to neutralize ‘it’s not your coast it’s our coast’. A lot of the land ownership in North Haven is through the town, much of that property is public preserve. The one thing I still haven’t really nailed down is ‘who are the stakeholders, to whom does the project address itself?’. As someone who doesn’t live in a coastal property in Maine, it would be worth hearing from people who do. On one hand the coast can be used in a bunch of different ways, the foreshore and the intertidal are occupied by completely different sets of people who are there for work, not necessarily pleasure. I was hoping there could be a total bombardment of notation on these maps about, ‘this is where I dig for clams’ or ’this is where I saw an owl’ or ‘this is where I hope to build something ‘ to ‘this is where i fish’. But the potential for that to happen during COVID, I’m not sure. At this point I have so far to go with just producing the property maps that my ambition is to produce them and get them out and let that try to guide the conversation from there.

In the discussion of locals in relation to people from away, is there consideration in this project for the Indigenous community and Maine as occupied land? When we talk about the word ‘local’, what does that mean here?

So far, no, would be the short answer. Some of the people from the islands I’ve spoken to have said “oh we’ve been seasonal residents of X for many generations, and we feel like we’re almost more local than someone who has moved there for a work related thing”. So it would be interesting to add that element to the project and try to engage with that, because the coast is in some ways a very intrinsic and almost mythical component of Maine.

In an email the following day:

I’ve been thinking about the question you asked me yesterday about First Nations’ ownership and occupancy of the coast in Maine and how that brings up a temporal element to the map (i.e. who has owned the coast and when). A map that overlaid historic ownership with current ownership would be really interesting! Furthermore, such a map could speculate about future ownership- if sea levels continue to rise, coastal ownership might transfer to those who live on property removed from the waterfront right now, as existing coastal tracts are submerged. A map that speculates who stands to inherit the coast would be really possible too.

You’ve done quite a bit of cartography in your practice as a visual artist, can you talk about the intersection of fine art and cartography?

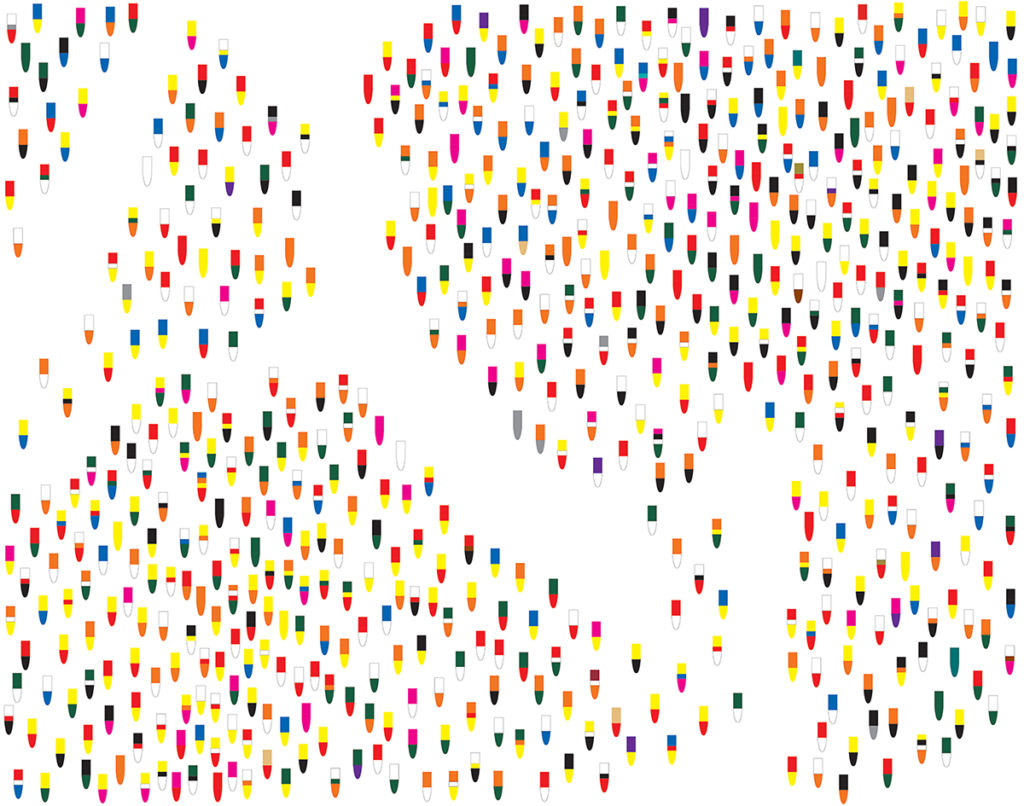

I went to graduate school in London and a pair of professors there formed the duo Cooking Sections. They do a lot of research-based performative art and research-based documentation of food issues and the ecological intersections of humans and non-humans. They really helped spark the understanding for me that a research project can in itself be an art project. Ghost Line is a really dry form of cartography because it’s just listing names and addresses, but I think that might attract or allow for a certain group of people who are hesitant to engage with something as an art object, and see it as ‘oh this is data’. Hopefully the conversation that comes from that can be moralized, what does the data mean? A map is totally a narrative device, I’m not sure I have a handle on my narrative yet. Maps have never been a scientific endeavor, it’s always been a commentary and statement about belief. There’s always been some kind of trojan horse agenda that’s been pushed through a map. Whether it’s sea monsters on the perimeter, or who is in the center of the map. To say, ‘oh well it just presents a dry set of data’ is really just not true at all. The only time I ever saw maps in museums growing up was in historical society contexts. I think it could be an interesting viewpoint to have in another type of space. I think to look at a map of 6,000 properties and say ‘alright I get it, there’s a lot of different people living here, so what?’ it’s more compelling sometimes to just zoom right into the micro and say ‘on North Haven there’s people from Arizona living next to people from New Jersey, next to people from London, and Maine, and California’. The coast in some ways is a micro congregation of embodied energy people are using to get to this spot. That can spark interesting conversations about how globalist the coastline is. I got into that through the lobstering project thinking about how the lobster have caused a huge amount of territorial disputes, local, state and international. The last piece of disputed territory between the US and Canada is over the lobster population. But the lobsters don’t care at all, they don’t identify borders.

While I don’t have aspirations for this project to be performative, the map can be totally all over the place in what it shows, and to speak about the coast, I think there could be a performative element to it. This could help spark more dialogue about what does a half occupied coast seasonally mean, and is that a bad thing. I work on a farm up in Pembroke on Cobscook Bay right by the Canadian border, and to be in Washington County versus Cumberland County is a really different lived experience. It’s not like Maine exists as a cohesive chain of identity.

The difficulty for me with Ghost Line is the long hours and low pay of getting to a spot where it can transcend the slog. I’m not quite at a place where I can spend the time to map the coast, I just don’t have the financial wherewithal to put aside time for that. All the information is publicly available, so anyone who wants to can find a tax map. It’s just that one degree of separation where the map and the list are not together, and I really don’t know if it could move into another realm. That’s been my internal monologue, is a continuous rationalization of why the project could be interesting. I’m so tired of sifting through a 600 page PDF of who owns what. One of the things I loved about Cooking Sessions is they had an obsessive, demonical pursuit of one subject for each project. They did a project on salmon farming in Scotland, and they found a color fan developed for salmon farmers to dye the flesh of their farmed salmon to make it look like wild salmon. That part research but part art is a really engaging way for me to think about art.

Is your thought that the publicly noted maps would then come back to you and you would recompile them or they would be more for distributed use?

In the Hail Mary scenario where they can be notated, I think it would be really interesting to then disseminate those maps, by making copies of them and distributing those. Maybe the easiest way to do that would be to start some sort of web platform, because maps are totally unwieldy, there are very few contexts in which maps are easily engaged with, and maybe an infinitely zoomable image is one way to do that. It would be cool, in another pipe dream scenario, to display them at a big table and have people come in and notate. I think the real document that I’d love to distribute in an ideal world would be a base map which has a scan of footnotes.

There was a really amazing project at the 2014 Venice Biennale, a studio in Italy put a series of geocensors on a glacier on the Italian-Austrian border. The glacier had moved about a hundred feet since the border was delineated, so in reality the border between this section of Austria and Italy was constantly moving. There was a robotic arm that was plotting the border every half hour in Venice while the border was moving around. A live document like that where you’re seeing, for example, in the fall this is how the coastline is used, and in spring this is what’s going on, could be really interesting, if the project had a larger feedback loop. But that is so far beyond my technical and intellectual abilities to orchestrate. Maps are often stuck in this Victorian, ‘this is a scientific and accurate depiction of something’ ideology which is never ever true. So the notion of the map as a more fluid document is cool to think about. Another 2020 Kindling Fund Grantee Bare Portland had a compelling ethos about their project, they were making a map of this collection of objects through performance, a speculation about what a life might be like. The map as a two dimensional document is one thing, but there are historical maps that were little carved objects. Maybe 15 years from now we can talk about how Ghost Line is developing and I’ll be carving big sculptures. I worked for DeLorme for a summer in college and I really loved maps my whole life, but I’ve never really been critical of them or critical of the information that is being given- or withheld- on a map. To talk about agendas, maps are just legitimate enough to convince people of their information, they have the allure of legitimacy despite the fact that they can be completely nefarious in their intention.

You lived abroad for a number of years, why did you make the move back to the States?

I worked for five years as an architect before moving to London to get a Masters in architecture. Through that whole seven year process I learned that I really didn’t like sitting inside at all. I lived in a bunch of really big megacities, I worked in Beijing for a year and a half, and then spent six months working on a chainsaw crew in northern Maine, and then moved to Copenhagen then back to hike the Appalachian Trail. So in this back and forth, I grew up in Maine but hadn’t really lived here in a decade. I had just done this project on lobstering, from London, which seemed completely backwards, or maybe indicative of where I should be. I finished up my program in London and, as my mom put it ‘it’s the first time you’ve been within 2,000 miles of us’. I have never really been an adult in Maine, I’ve only been back for a year, so it feels like I’m still getting to know the state.

What other projects are you working on or thinking about?

I just self published a four act play, the premise is once a year all the trees get together and have a big dance, it’s called The Root Ball. It’s just about what happens at the ball. I work for the art collective Pickup Music Project, PUMP, based loosely in Boston, we do large scale public musical instruments events. Pre-COVID we were working with a museum in California hoping to do a section of the border fence between the United States and Mexico that was playable chimes. That project is on hold, but in the absence of public events, we’re thinking about how music and public space agents can be brought into the house or family unit.

Do you hope to stage The Root Ball?

I was walking in Edgecomb, and there were a bunch of tamarack needles on the forest floor, and they looked sort of like confetti after a party, and it made me think ‘that’s cool they had a big thing last night’ so one section of the story was going to be sounds of the ball, what does it sound like when a bunch of trees are dancing together, which led me down a wormhole of ten hour YouTube recordings of oak creaking in the wind. The play evolved out of that, where all the characters in the play are trees and all the dialogue is a transcription of the sound of that tree moving in some way. The Oak says “Skirok-tok-tok-tok-tok” and the story itself is in all the parenthetical stage commands. I feel like in some ways those voices are not mine to give them, and I think I would feel uncomfortable if a bunch of humans dressed up as trees. I don’t have further ambitions for that so far. A friend of mine did a project where he took Henry V and removed all the dialogue and just left the stage commands. You don’t really notice them, but it’s like ‘enters, exits, draws sword, exits, fights dual, draws swords, exits, enters’ I feel like the margin notation is really an interesting way of thinking about the actual drama that’s unfolding, because all the action is right there.

Are you reading anything recently?

My time allowances and attention span are well suited to short stories. I love magical realism, I just finished a really dark story called The Boy Who Stole Attila’s Horse, which is novella about two brothers stuck in the bottom of the well, and through the course of days understand that their only means of escape is to lose their sanity. Which was totally the wrong choice for a pandemic read, so the one I read after that was an Italo Calvino story called The Nonexistent Knight, about a knight in Charlemagne’s army that had no body, but was a stickler for knightliness, so that was a nice counterbalance to the two brothers who went insane in a well. My nerves are shredded. My mom and I went on a backpacking trip together recently and listened to a Harry Potter audio book which was awesome.

I have to ask about lobster shell toothpaste.

When I was doing the project on lobster I found that something like 30% of the lobster is shell, and that just gets discarded when it is consumed. The chitin in the shell is really great for your teeth. It was a weird side tangent, shells oftentimes are used as fertilizer, but could it be something else? So I dehydrated a lobster in my tiny oven in London, my flatmates were furious, our flat smelled like lobster for two weeks. I then put it in a food processor with rosemary, salt and baking soda and made a tooth powder. It smelled like putrid lobster from day one, so it was really hard to know if it was fully dehydrated and I really don’t trust brushing with it anymore. I get sidetracked really easily on things like that. There was another month where I was fascinated by lobster sex. It was just a pinball project.