Combining an oral history of Christopher W. McDonald’s visual art practice with reflections on the present moment in art and technology, this conversation with SPACE touches upon McDonald’s reflections on doom scrolling, tarot reading, research materials found in the studio, and more.

I. (coding video game art: 2007 & 2021)

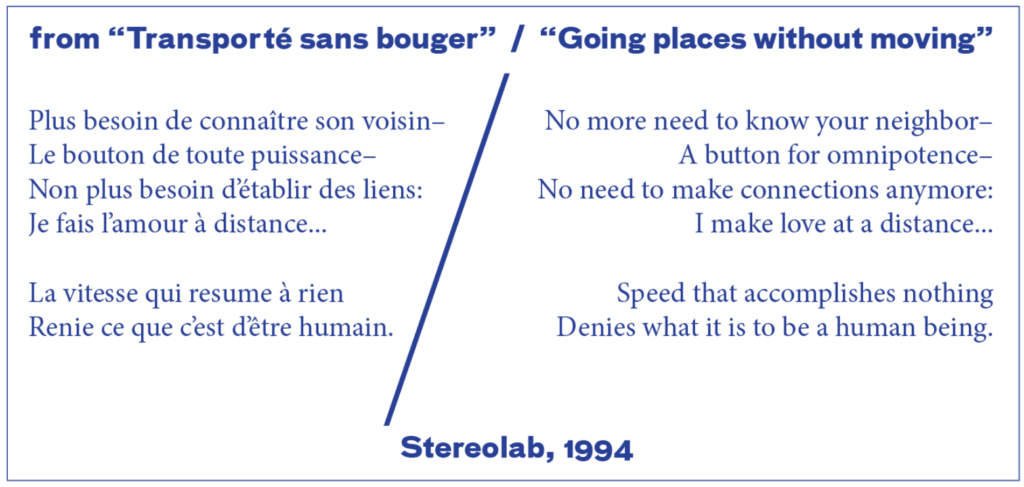

You shared a Stereolab song–the title translates to “Going places without moving”?

Yeah, it has always been one of my favorite songs of theirs and it means a lot to me. A lot of work in this show relates to the lyrics–there is something about the insane speed of Moving Line being generative but also circular and not really going anywhere. And something about the easy access or constant availability of the web cams. Rapid fire doom scrolling dark ages!

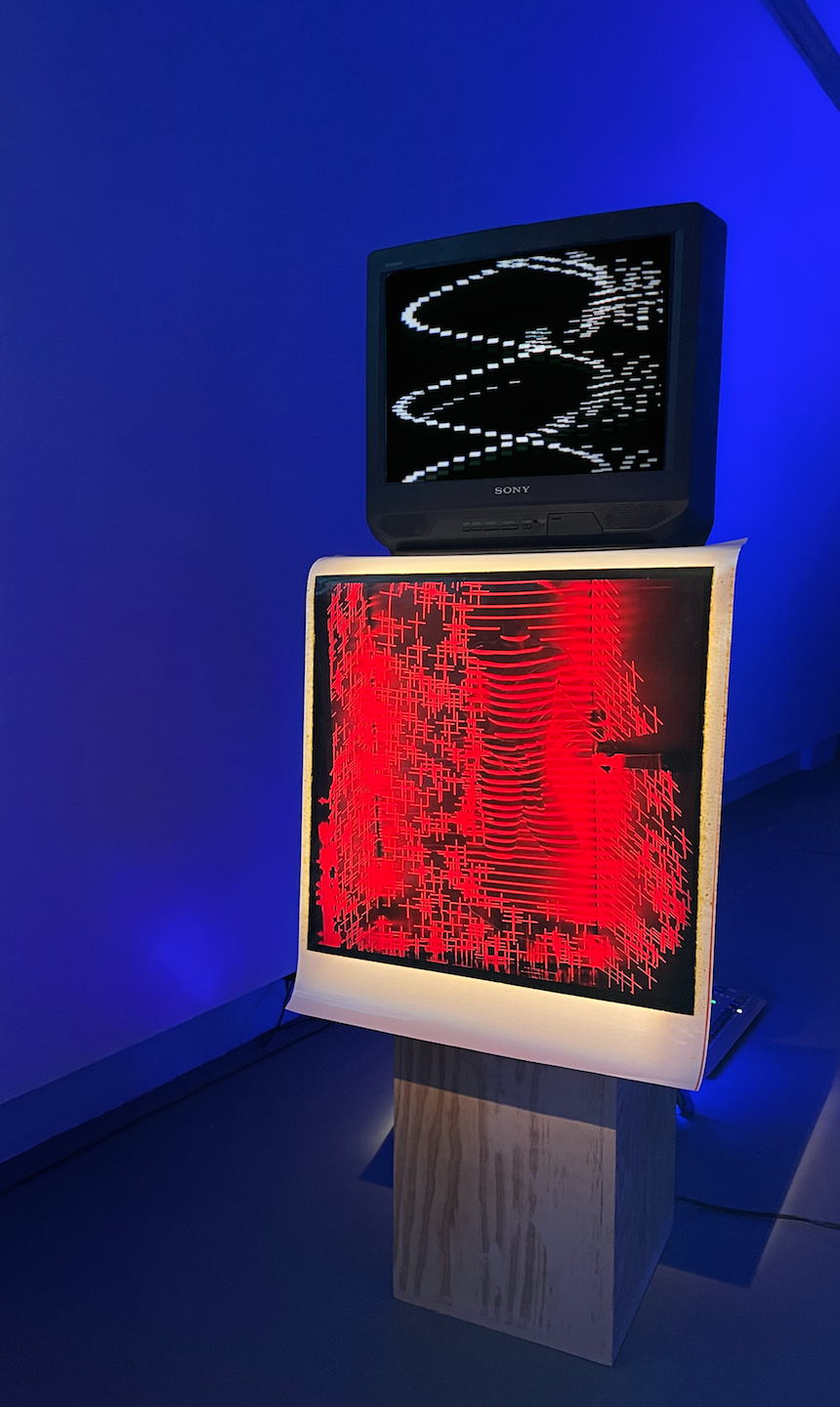

So this piece was never fixed, you’ve gone back to edit code, you are returning to the collaboration with the TV. Is Moving Line some sort of minimalist opera?

An opera in five acts! I guess.

Could you explain the concept of a “vertical adventure”?

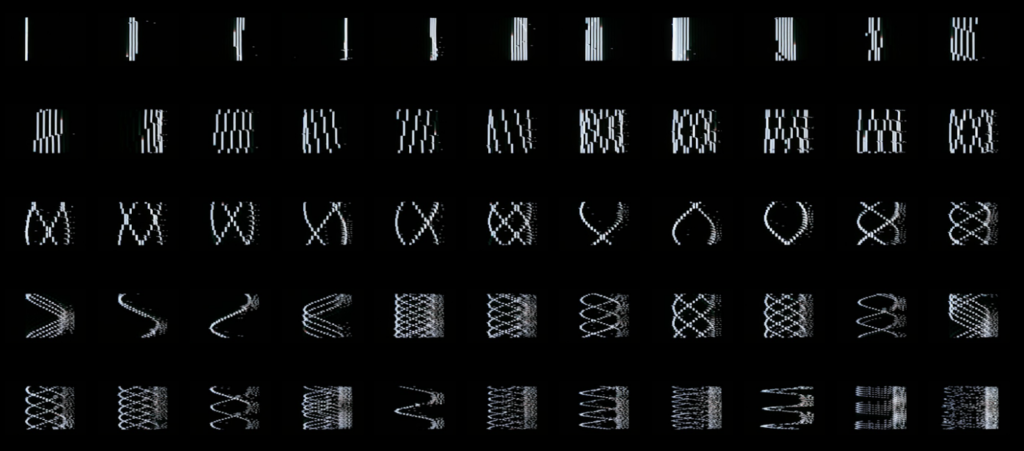

I travel a lot for work, all over the world, and I love to learn about other cultures and eat new food and how they talk about art. But I am also just as happy to explore my own home and go deeper and deeper fractally. The deeper you go into the familiar, the more magical it can become again. Moving Line has this too–because it is literally just moving left and right, across the screen, faster and faster, and as it starts to get too fast, the television starts mis-seeing it worse and worse, and it starts to smear across the screen, and at some point it moves so fast it appears to move vertically on the screen, but it is still a line moving left and right, but it is being mis-seen by the TV so it starts creating vertical motion.

Would this be glitch-art?

Ah, I never have been good with genres or labels, but it is basically a collaboration between this little micro-controller and that television’s perspective on life. The TV wants to see things at 60 hertz but it is getting a signal that is 15,000 times that. So it thinks it is getting a signal, and is still getting the 60 hertz blinking that it needs, but it doesn’t realize it’s getting a signal much faster than it thinks it is, so it starts seeing the message as crazy 3-dimensional spinning blocks. Is that considered glitch art? Probably!

Moving Line carries meaning and weight to me–especially when thinking about perception and signals–for example when someone is struggling with mental health–or just chemistry or receptors in the brain–sometimes the effect of what is being taken in, or read appears different than the reality.

Well-spotted. I think people may have trouble seeing the “humanity” in digital work like this, but it really is about context and understanding in a broad sense. I worry “glitch” is always a little too focused on the digital/technological and that might elide the human drama I hope the piece has. Humans are every bit as susceptible to misinterpreting messages based on their own contextual frames and biases. We spin simple data into chaotic webs. Moving Line uses a collaboration between a TV and microchip to explore this problem but it is by no means just a reflection on technological limitations.

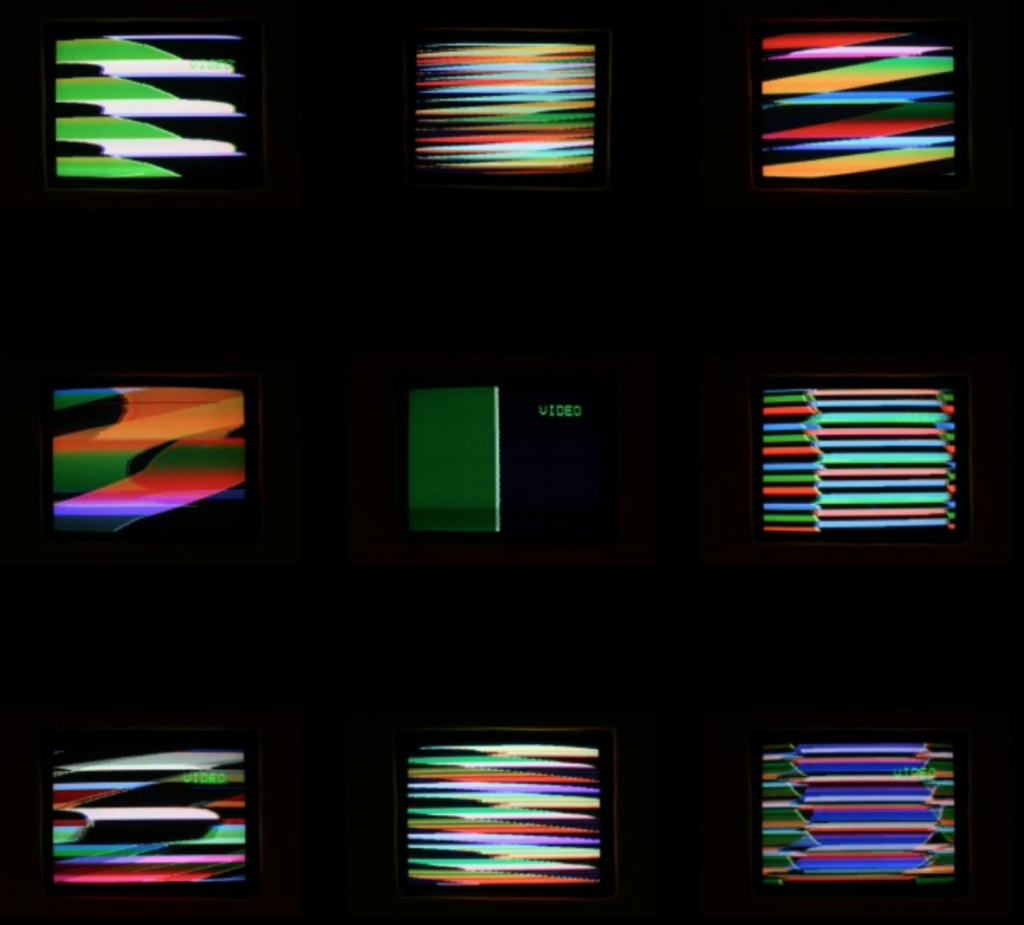

VPDEO GAME (2008) is similar, it changes the rate that the blinking is happening so it is giving the TV different multiples of the speed of signals that it should be getting. That one is literally a sideways Rothko–it is one field of green and one field of black, split down the middle of the screen. It makes all these crazy colors and patterns as it cycles through different speeds. In that one the TV keeps losing the signal because it is so crazy, much crazier than the moving line. There is something wrong or so beautifully right with the Sony Trinitron bios that is running the TV that it’s almost like its memory gets overloaded or too stressed out trying to flash the video.

But if you do the right combo of fast changes by playing the drum sequencer with the little + and – buttons it starts swapping letters in and out and will start grabbing the wrong letter from its little sprite memory repository of letters. It became this video game with a hand written scoreboard where you give yourself how many points you feel you deserve based on the letters you were able to swap out of VIDEO. VISMO. VPDEO…

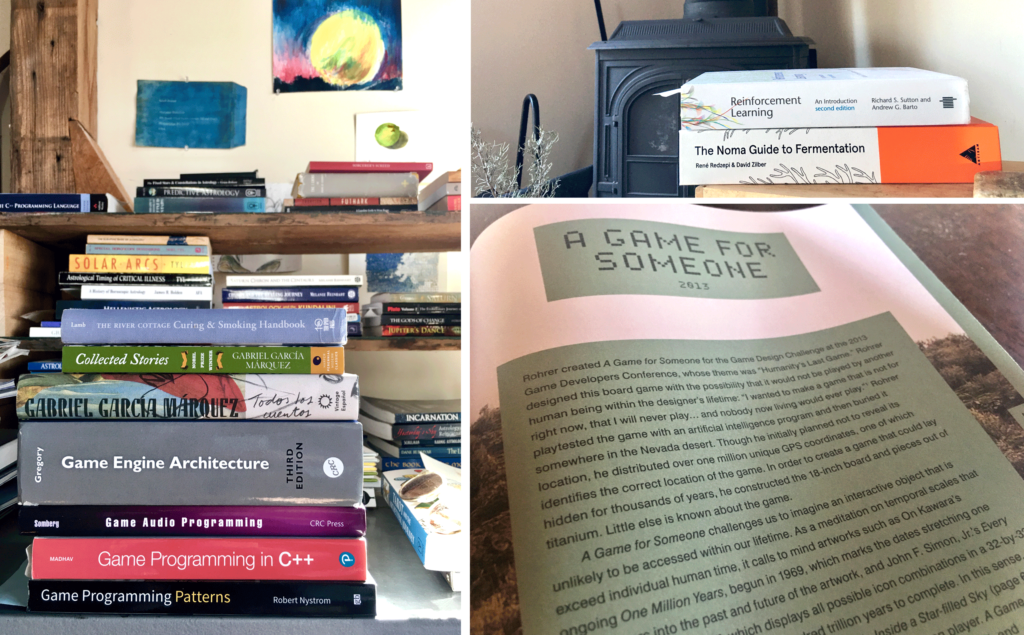

What caught my eye when visiting your studio was how many books were around and the variety –one was The Game Worlds of Jason Rohrer. I would love to hear more about your thoughts on game design and human-machine relationships as it seems to be an ongoing thread.

That book was from a retrospective show at Wellesley College. I have a lot of respect for his games because they often do not have anything resembling your standard video game trajectory of a beginning, getting points, and ending. Some of them are much more absurd. In one game all you can do is move right, but when you move right you age and die. You can stay in one place if you want, but then the game doesn’t progress. So it’s a sad and funny game where you are experiencing the inevitability of the end. [Rohrer’s games] are playful and thoughtful. It’s clear when you play them that the ideas going on are as important as racking up a high score.

As we were looking in your flat file at past works, I noticed above it was a stack of books related to your current project which is reinforcement learning?

Yeah, the library above the flat files is game engine architecture, C++ programming, tarot, astrology books, and AI reinforcement learning. And it actually does go together because I have been building a tarot and astrology program for the readings I do for people. It goes into the chart and takes the cards from the tarot reading, takes the astrological chart, and it will spit out all of the correspondences because every tarot card has an association with either a different sign or 10 degrees of the zodiac or a planet, and it ends up kind of snowballing into a lot of information to keep in my head at once, so I wrote some software to help me cycle through that really quickly to check for these relationships so I can help answer people’s questions. And I have a game I want to make that is a kind of generative storytelling adventure that does tie it all together…

II. (learning to draw with machines ~2008)

You recommended watching AlphaGo–a movie documenting the 2016 Google DeepMind Challenge match where AI is pitted against Lee Sodol–the number-two world ranked Go player at the time. In game four the commentators are talking about the difference between human and machine in strategy and emotion: “[Lee Sodol] feels this sense of responsibility or burden”–he is playing for humanity. When they announce “It looks like AlphaGo has resigned”… you hear cheers from the crowd overlaid with the following commentary “it is clear why there is cause for celebration–people felt helplessness and fear. It seemed as humans we are so weak and fragile. And this victory meant we could still hold our own.” What was your take away from this film?

I liked the idea that the bizarre move [from AlphaGo] that the commentators didn’t understand wasn’t just a calculation error, it turned out to be a beautiful move because it was somehow playful and strange–and it won the AI one of the games despite it seeming totally random at first. I like how the human Go master that lost had a kind of reverence for the way the AI played and is now even exploring that new style in his Go playing…I would like AI to always be a helpful subservient tool, a creativity aid to humans. We see this in science with protein folding or extremely complicated problems humans cannot spatialize well. I like the idea that even in a field like playing board games that we can get insight [from AI] on how to expand our own practices and reflect on what creativity means for us.

This dialogue between human and machine reminds me of your early work–specifically and, body from your 2008 machine line series…

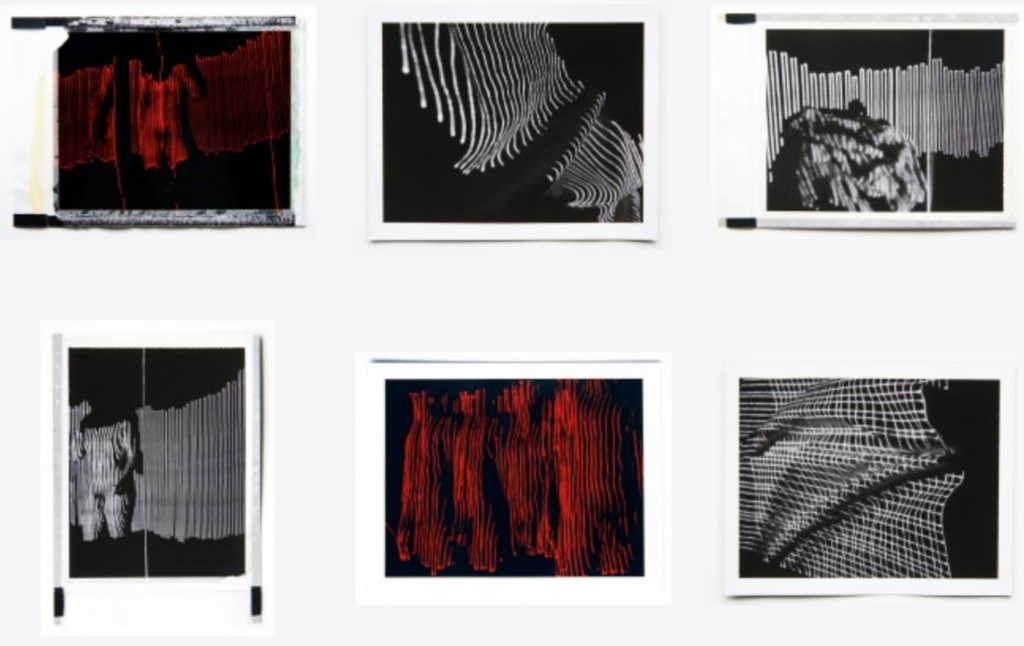

In machine lines I built these machines that would draw by moving light slowly around in a room and I would take long-exposure medium format polaroids. Because of the time aspect of those machine drawings–they are all long exposures, upwards of an hour sometimes, as the lights are slowly moving around–so they all have a durational or performative aspect. Some of them ended up being more explicitly performative where I would move objects around in the room while it was happening. In and, body is being projected onto my body. I did live performances of this too where I would be in a dark space and just holding very still and then doing some movement to interact with the light and change it.

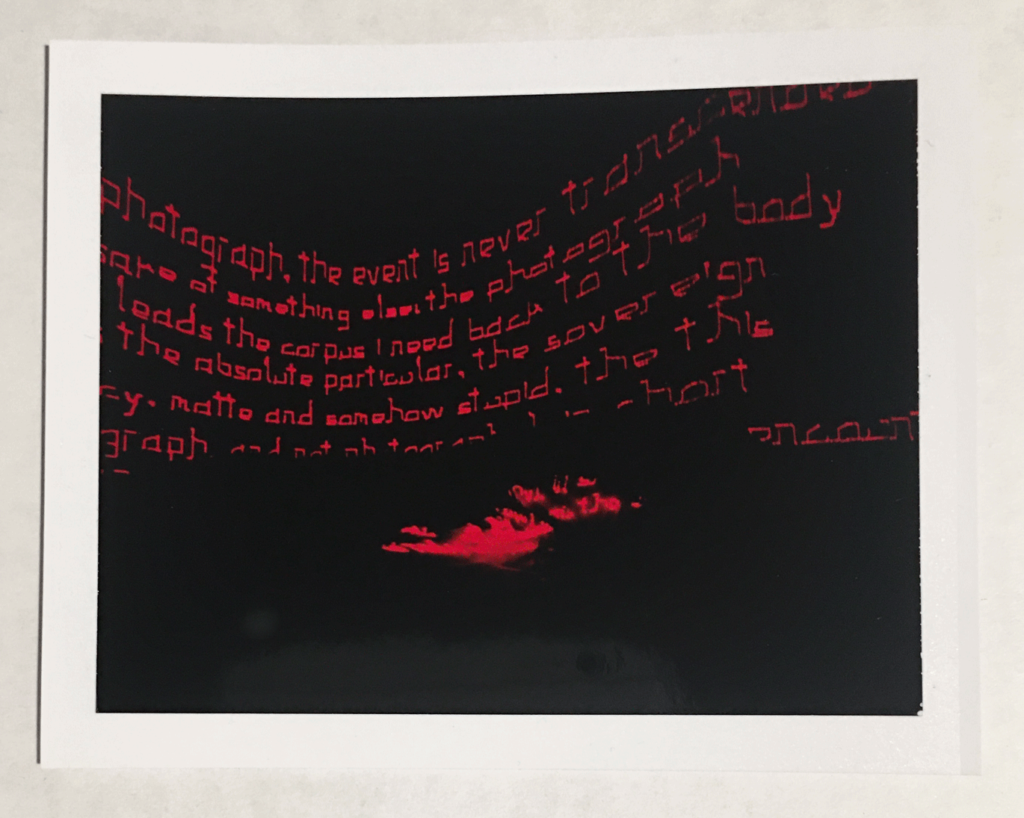

And you also programmed the machines to draw a typeface?

Yeah, so the machines could do RGB with 24-bit color, sometimes I would have the machines print out images, with both machines sometimes I would print out text. I think this text was about the body, the photograph, and the event, I cannot remember…Baudrillard? It seems very like ‘recently graduated from college critical theory’… something like the ‘photograph is not the archive, the body is the archive’ or some shit like that?

(Edit: It was from Barthes’ Camera Lucida, “In the Photograph, the event is never transcended for the sake of something else…” which I thought was a ridiculous statement at the time, even apart from the context of the work I was doing with the machines. In those long exposure photographs, we get essentially an archive suggesting an Event that didn’t exactly happen…)

But after four years, similar to AI teaching us new creative moves, I was starting to get jealous of the machine’s drawing. “Why don’t I ever get to draw?” The machines kind of inspired me to teach myself.

III. (learning to draw by hand ~2014–present)

Lets rewind, because in college you were not an art major?

I was a music major in composition and I did history of philosophy–one of those mash-up majors that was looking at psychoanalysis in the history of Science and Philosophy.

So the process of learning to draw then became part of your practice–it is very art school 101 to start with figure studies. How did you approach this task?

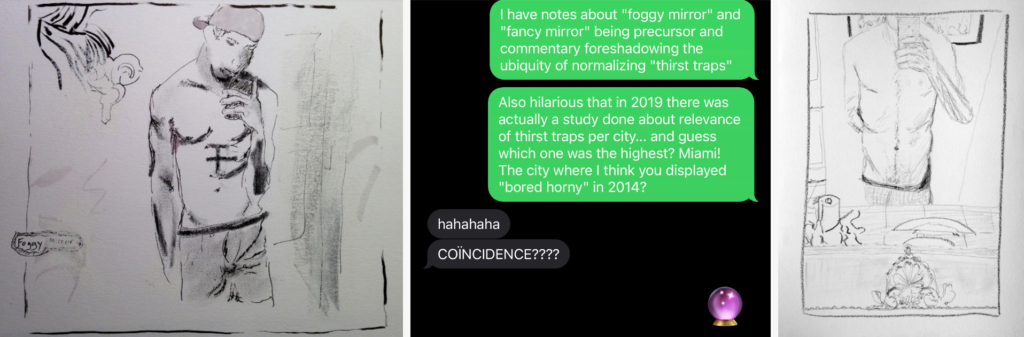

First of all I am a total hermit. So I was definitely not going to go to a local art class because I didn’t want to be around anyone. So where am I going to find naked people? The internet is almost entirely naked people, so I drew them as figure studies.

You first shared the bored horny drawings through text. It was a bit of a surprise. Here you’ve taken the time to study and draw a rather glib photo–an appropriated selfie–but this act seems to take the pornography out of it and just makes it sad and funny.

I hadn’t thought of it in terms of how much time the drawings can take, but there is obviously something very immediate and impulsive about dick pics–the framing could be amazing but totally bizarre and weird and the lighting and angles can be awful. But they are off the cuff, quick snap-shots. So then the amount of attention and time [to paint or draw] is kind of undoing the immediacy. The ability to actually frame–to give someone the view of you that you want them to see is more of a game changer than I think a lot of people realized right away in the dawning of the selfie age.

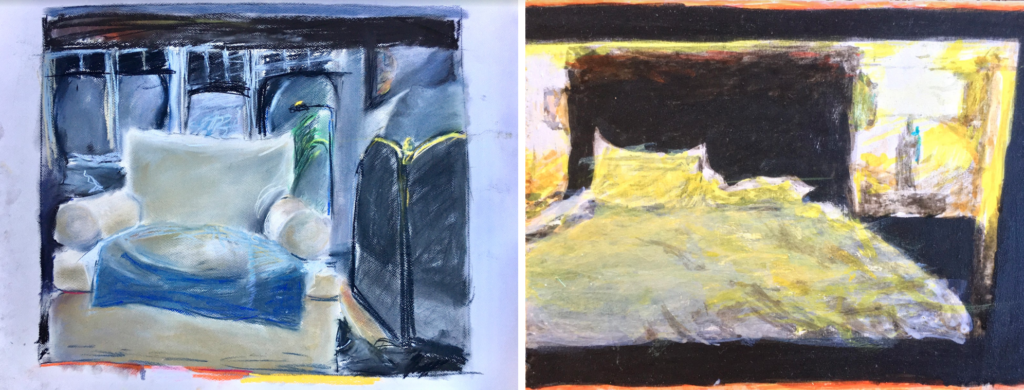

The Rooms–came out of the bored horny series because I used webcams a lot for source material. And while I was drawing one day the person left the room and I realized all of a sudden how much more beautiful this empty chair in a blank room was. The absolutely unlimited narrative of this empty room becomes much more interesting.

Empty vessel?

Yes, Heidegger has a concept for it–“das Ding” (the Thing)–and uses it to talk about Van Gogh’s painting of a peasant girl’s shoes. The idea of a pregnant absence–yes, they are empty shoes but what is evocative about them is what is missing. It is like they are a vessel holding the absence. The emotional energy of this missing person. All the possible stories. Absence as a starting point is very provocative.

Are you seeing The Rooms in a new light now and especially in advance of your upcoming installation at SPACE–where they will be suspended and seen together for the first time?

Seeing so many snapshots at once will start to read like an instagram feed or something. Putting up 30 or however many we can arrange–hanging loose, grid-like from the ceiling and in the window–will definitely start to read like a webcam directory preview. And hopefully the ones hanging in the space will feel like glowing screens, especially from the street at night.

In your drawings you seem to be documenting these idiosyncratic moments in our digital culture–I’d love to hear about The Rooms you did on granite. They don’t read as macabre tombstones, but more a way to preserve this moment in time?

I have always been obsessed with cave paintings. When they first found Lascaux and these crazy cave paintings [in the 1940s] they brought in Picasso. So all the reporters are waiting outside the entrance of the cave for Picasso to come out, and when he comes out he looks totally shaken and says “We have learned nothing in twelve thousand years” or something like that, hahaha! Everything he saw looked so perfectly modern, expressive, and cutting edge and full of humanity. Apparently a lot of cave paintings are egg tempera too. They would mix yolk with ochre or charcoal and it would last longer. I make my paint with eggs from the chickens on my farm and I use a lot of ochres too!

I started working on rocks so I wouldn’t have to worry about paper bending or decaying. In theory, tempera on rock is very stable. You have to worry about mold, make sure it’s not too damp in the environment…

When I see The Rooms on granite, I think about them in terms of a possible digital dark age, where there is lack of historical information as file formats are extinct, hardware is corrupt…

Totally. When I am working with Ragnar Kjartansson and other artists I am doing a lot of high-tech stuff–people don’t think of his work as computer art, as they are in the experience of being in the space with these very romantic landscapes and emotional music. But I am dealing with all the super nitty gritty technical details of it from recording it to mixing it and figuring out how it can be installed. And once I started working with him, I wanted less and less to have anything to do with technology in my own work because I was so tired of working with it all day long. Dealing with bitrot and storage format wars, what do we do with the hard drives, who is going to pay for the magnetic tapes in a mountain in the Swiss Alps… so more and more I just wanted to be working with eggs and pigments, and rock. Just trying to go as analog as possible. I like the idea that someone comes around in 10,000 years and all the paper and canvases have decayed to dust and they see these empty web cam rooms on granite and ask “Who were these people of this ancient primitive civilization?”

IV. (new environments)

What prompted your move from Brooklyn to a farm?

I was working at a mastering studio in NY as a sound engineer, and working on my own art and felt NY was just too noisy–not audio noisy, just the rhythm of what people cared about for art was too weird and aggressive; “This month we are doing pedagogy and next month we are political again, oops here comes the return of the figure, etc. etc.” It was just too scatteredly trendy and I wanted to have some space to think about what I wanted to do. The guy I was working with at the mastering house said ‘If you want a change of pace you could go to Banff and be a sound engineer there.’ So I applied and was hired in 2009 to be a sound engineer for three months in Banff, Canada, from January to April. That cleared my head and I got to do some of my visual work with the machines there too because there were some kind people in the visual art department who were interested in my work.

Banff, an artist retreat in the Canadian Rockies, is where I met Ragnar. I worked on a video for him called The End which I believe he showed at the Venice Biennale in 2009. We were divvying up jobs for that week, and they were like “we have a violin concert, a piano recital, and then we have two Icelandic guys who want to shoot country rock video art in the woods.” And I was like “I’ll do that one!” That was perfectly suited for me.

I have been working with him for 12 years now. In 2012 we made The Visitors which took off so maybe people would know him from that, if not from all his other work. When I was done at Banff, I never moved back to the city.

In your current recording studio at the farm there is a framed drawing signed by Ragnar. Are you in the red jacket?

Oh did you take a picture of that?! Yes. That is really funny as it sums up my entire career with him. I am standing outside of the wind-break/heat tent–it’s a blizzard outside and we are on a frozen pond and it is literally the temperature where fahrenheit and celsius meet again below zero, negative 30 degrees or something. We were all getting frostbite and I am standing outside the tent holding the material to keep it from blowing so that we don’t hear it in the microphones. It’s ridiculous, maybe you could have been able to hear it in quiet parts if I wasn’t holding it, but for a lot of the shot the drumming was going to be so loud that no one would ever notice it. It’s a pretty good picture of my maniacal, obsessive attention to detail, “We cannot have this tent shaking, you will hear the plastic and everything will be ruined.’ And he did a drawing of that for me.

This drawing was actually a ransom payment because I stole some art of his. It was a really weird thing, I took the score for the piece The End. He was like “OMG someone took this thing I drew and I really need it, do you know where it is?” And I was like “I…I…stole it..” And he was like “You did?! That’s great. Can I have it back then?” And I was like “Of course, I thought you didn’t need it.” He said “Well if you give it back to me, I’ll give you another piece.” Actually, that might have been a different one he drew for me of drums… Maybe I stole two things??

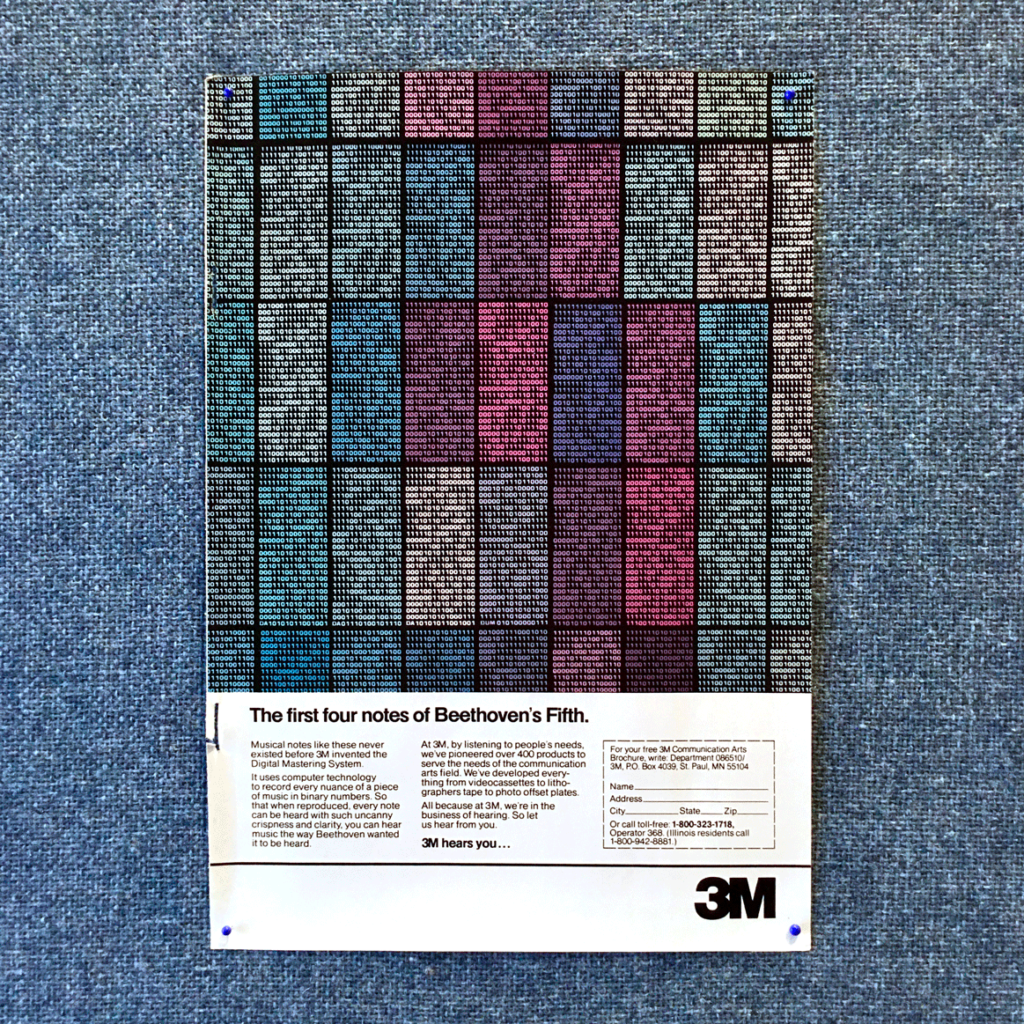

Next to that drawing in your studio is an advertisement for 3M with the copy “The First four notes of Beethoven’s Fifth”. It looks to be maybe from the late 70s…

Yes, that’s amazing it was one of the first digitized pieces of audio that they made. They must have been digitizing things for post-production and reprinting them to vinyl and cassettes??

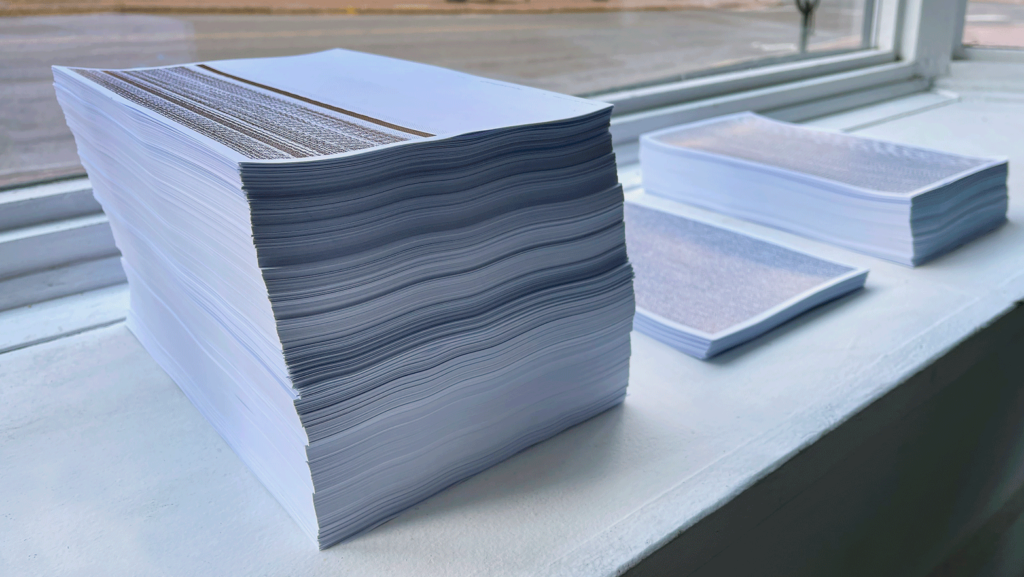

There is a piece of yours–a collaboration with DaQuan–1001001… I was curious how that might relate?

Yes, so that is a 3M ad from a National Geographic and the whole background of that page is just 0s and 1s, depicting the first few seconds of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. And DaQuan Motley–this really awesome musician, rapper, and artist–we met when performing together in 2006, and we made a song called Digital Lullabye for an album we collaborated on together in 2013. We thought it would be interesting to try to do something sculptural with it and made a series of 3 stacks of print outs: the high res studio format, the CD mix down, and then the mp3 version. So there are three stacks that exhibit the weight and material of sound in the amount of data between the three formats. The studio one is over 1500 pages, the MP3 is less than 100. It’s printed out as little bit/pixels though, its not 0s and 1s. 0 is no pigment, 1 is pigment. It’s funny I never thought about it being related to the 3M ad, but obviously they are! So the Digital Lullabye piece looks kind of like tire tracks, like noise or slightly structured static. There are some clear repeating patterns. Looks a little like a winter car tire tread. At the time I must have known about the John Cage [and Robert Rauschenberg] tire track print…. So I would say that was an inspiration too then. Always thought of DaQuan and me as Robert and John!

A few years after that album and the stacks sculpture, DaQuan and I had a catastrophic falling out (that was luckily temporary) and around the same time I had a catastrophic hard drive failure in the studio (in which some working files were lost forever). So, I think we actually only have the .flac files for that whole album now. At the time the stacks were thought of as a “carbon copy” of the work that could in theory be used in a thousand years to reconstruct the waveform of the song. Now the stacks are actually the only remaining copy of the original data. But we do have the .flac file playing in the window on the hour. Digital Lullaby Cuckoo Clock!

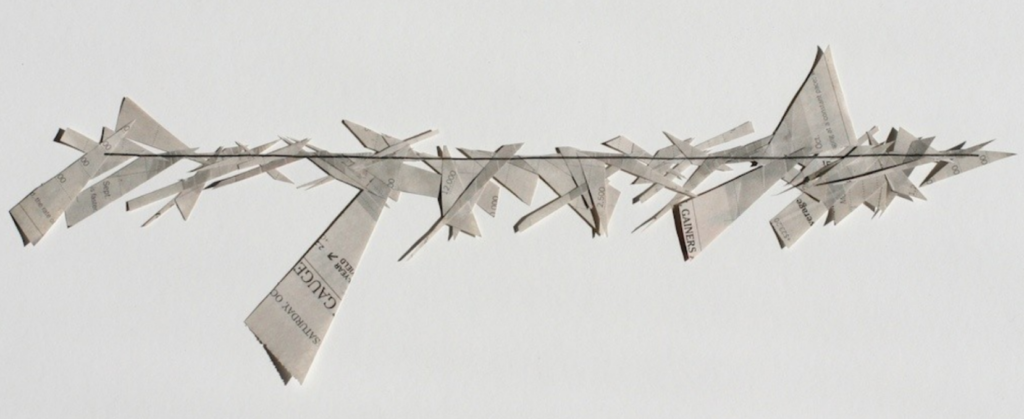

Yes, I love their collaborative work [Automobile Tire Print (1953)]. I do feel some of your 2012 pieces channel that mischievous Rauschenberg spirit, where you are using found materials and recombining them, but also there is a minimalist thread–like in your flatline, utopia series?

In flatline, utopia I was taking stock market graphs from The New York Times, specifically indices like the DOW or S&P that charted a week or a whole year. These are small graphs–3×5 inches or so. I would cut these up at every vertex, rearrange them, and glue them together so they are just flat lines because I don’t believe in economic growth. In retrospect, each one was as much an attempt at homeopathic magic as a work of art. The economy is basically an Earth-sized Ponzi scheme… I would rather have a beautiful utopia where nothing grows or declines. Visually, the reconstituted line has a lot of depth but also weightlessness, seemingly detaching from and hovering above the shards of newsprint. flatline, utopia explores an idea of paradise as a place that appears to us unchanging.

V. (time/scale/production)

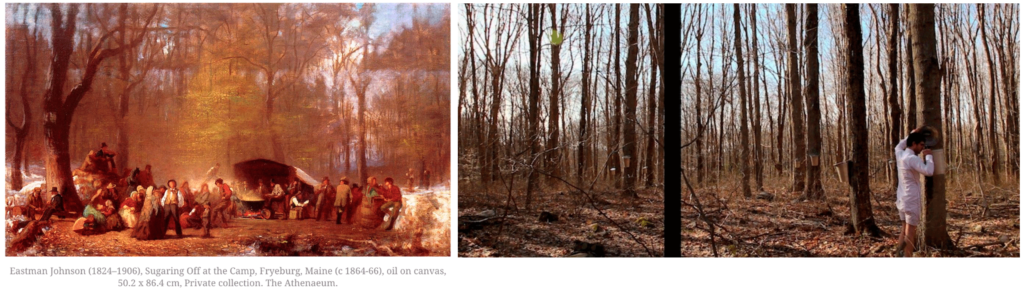

You have a video piece Sugaring Off included in the show at SPACE…

Yes, it’s a video of a white-socked, white-boxer shorted, and white button-down shirted person, wandering through a forest, possibly stealing sap. It is definitely a character of sorts… This was inspired by Eastman Johnson’s painting studies of sugaring parties in Fryeburg, Maine. They are paintings of people in the woods, dancing around a big fire, there is almost a Crucible vibe to it. These were made in the 1860s–I think before the Civil War–and there was an abolitionist aspect to it. Syrup in the North became an abolitionist symbol, so there is kind of a utopian vision of free people partying in the woods, making sweetness. But work for your own damn sugar. Work hard, party hard. As far as I know this was part of the collective mind of Northern New England at that time, the pride of making your own sugar.

It’s crazy when you make stuff yourself and you realize what goes into it. It’s something like 40 gallons of sap going into a gallon of syrup. When you see the input and output of processes like that you realize you take for granted that this product is just there, you don’t think about how much energy and time and space goes into producing it. That comes up a little bit in the video too, there is a post-apocalyptic tone in there maybe. There is something strange with this figure–there is some kind of feeling that things have collapsed.

The more time that I spend [on the farm] doing things from start to finish, the more obvious it is that the scale of production and consumption that is going on is unsustainable–and this relates back to the flatline, utopia pieces–it’s just obviously unsustainable to consume as much as we do because this stuff takes up time and space and has such an ecological impact. When you see it in its final packaged form, all that background is elided. So I grind my own grain, make my own buns, make some cheese and slaughter a goat to make a goat cheeseburger–man that tastes great, but is a lot of work. Slowest food movement.

Sugaring Off is a good piece to revisit in this time–for all the themes you noted but also for the incredible sense of dislocation between this person and nature. For 2020–2021 this reads as “did this person get lost on his way to a zoom meeting?”

Exactly. The figure definitely seems out of place. This is what happens to many people in society when they have to do something for themselves. Things fall apart! They realize they are in over their heads.

With Sugaring Off and Moving Line–I keep wondering if there is a trail of endurance art in your work. In your words: “from the point of view of performance, drinking gallons and gallons of sap so quickly is both a feat and an (unwanted) indulgence.” That level of physical repetition–reminds me of a bit of the recording you did in 2014/2015 for The National and Ragnar–A Lot of Sorrow.

I don’t think I would call Sugaring Off endurance art… But it is a repetitive process and the piece was over after I had gotten through each bucket.

Roberta Smith wrote for the New York Times that the A Lot of Sorrow performance and recording was: “Minimalist in structure, the same song over and over again, yet unimaginably expansive.” And then she gave a shout out to those behind the scenes–“credit for the sound, goes to the sound crew, which like other technicians involved has to devise their own form of endurance art.”

I forgot she wrote that, but I think about that [piece] all the time. The making of those long video works like A Lot of Sorrow is some kind of endurance work. Sometimes, especially early on when we were trying to record long Ragnar works, Tomas Tomasson (the cinematographer) would be madly trying to swap and copy CF cards. We’d be walking around the Carnegie Museum in our underwear so we wouldn’t have pants sounds in the recording and every 3 minutes Tomas would have to run over and put another card in because that was the only way to record them and they were maybe 32GB cards at the time if we were lucky, hahaha. So it is its own kind of mad exhausting dash just to get everything recorded.

I appreciated that nod to behind the scenes work because when you experience Ragnar installations they often exude a kind of stillness–so the level of stress in making is very much removed for the viewer. Thanks for peeling back the curtain and sharing your experience in your professional work as well as your personal practice.

“Distant Pleasures” is dedicated to the memory of Ben Ari Sandler (1981-2021)