Guest curator Alexis Iammarino in conversation with The American Dream/Renny’s Delicatessen (2017 – 2023) artist Reniel Del Rosario.

Alexis Iammarino: Okay, well, where to begin?

Reniel Del Rosario: I don’t know. Let’s see. Should we talk about the project first?

It’d be nice to hear directly from you about the project and the significance, of it coming to Maine too.

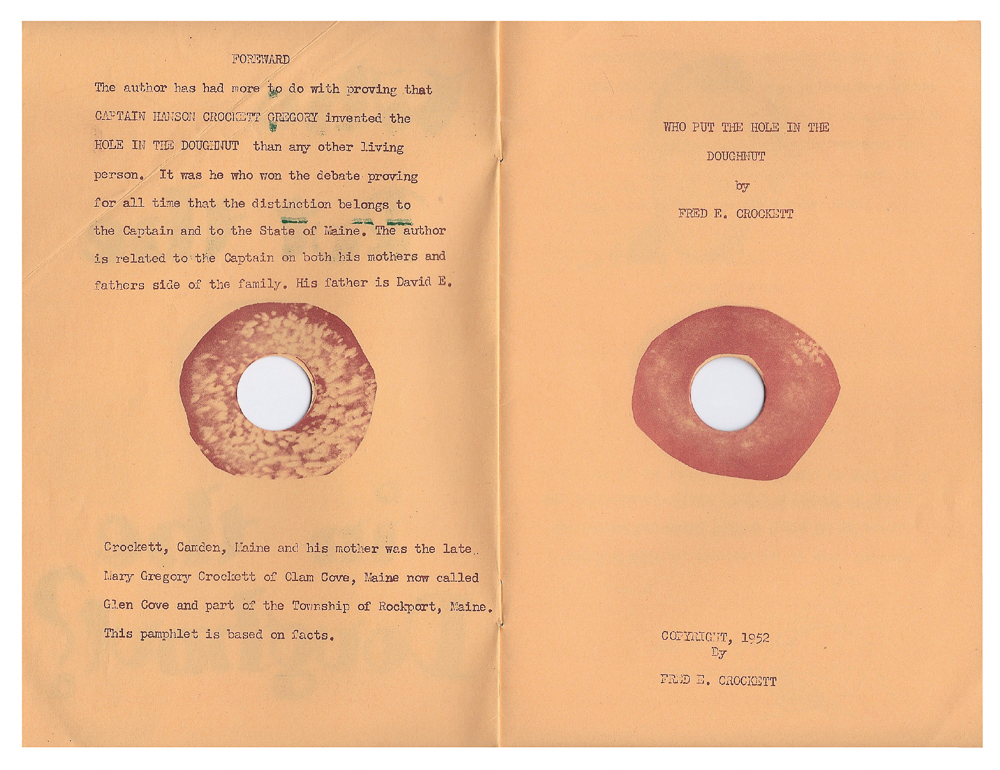

Well, I guess we sort of have to start from the very beginning. So we have to go back to 2016, which sounds like forever for me. It started off with me taking my first ceramics class and making probably the first donut during that time. I remember making the donut because it was just the last scrap in the bag of clay, where I don’t have enough to make anything. So I remember making a plain donut—no fancy-looking glaze. It looks like a plain donut that was maybe dusted in sugar because it’s just slightly shiny. But I remember making that donut because it only took a small palm of clay to make.

So it was just this thing to make. And I remember thinking of that every time I would reach the end of a bag of clay, like, let’s just make a donut because it’s simple and it’s the easiest thing you could make. It’s just a string and then you’d join it together. So I remember that. And then taking ceramics again the next year, I was also taking a lot of classes that made me question my identity as an Asian American. And it led me down this other rabbit hole of trying to find out what Asian American-ness is and where I fit into that as an immigrant from the Philippines. And I found this video that talked about the history of donuts and the history of American donuts, specifically the pink donut box and how that was started by a family of Cambodian immigrants who came to the United States and they started using the pink donut box because they were taught by someone to use a pink donut box. Then this person became the source for other Cambodian immigrants who came over to be taught by him how to run a donut shop and use pink donut boxes. So it spread and became this nationwide sensation of pink donut boxes being associated with donuts and Americana and for me that was such an eye-opening thing because it was this symbol of Americana that’s Asian to a degree. It was breaking into the wall of cultural boundaries. You know, a discovery that they’re not really hard set.

They’re sort of like ocean water and brackish water where they mix together and things aren’t really a direct line—they move and flow. I got really into this weird boundary. So then the next year I did the first American Dream/Renny’s Delicatessen project being very inspired by the fact that there’s this Americana thing (a donut) that was so Asian to me and I felt like something similar to that was this mid-century, postwar American delicatessen where you can go in and get iconic American things like milkshakes, burgers, all that jazz. So I wanted to do this project and make them out of clay and also have a component of it where a big part of it is the buying and selling since postwar America was very oriented around small business.

I wanted it to be something that people could interact with and not just have as a still piece. And, you know, I thought that was such an ‘American Dream,’ the ‘American Dream’ of being a businessman, the ‘American Dream’ of starting from the ground up, the ‘American Dream’ of being an immigrant and starting from scratch and all that stuff. So it was like playing a lot with the connotations of…especially as an immigrant, the American dream, assimilating, and taking the form of America through its cultural cuisine. And eventually I started doing it as a whole interactive and public installation and it started to flesh itself out and become also about commodity and consumerism. The first one was in Berkeley while I was in undergrad, out in front of the art building.

I just set up a stand and sold these ceramic goods based on the price that I could find for an artisanal version on Yelp, because I wanted it to reflect that. A reason for that is because I was also doing a lot of research into Claes Oldenburg who did his ‘The Store‘ project in 1961. I messed up on the research somewhere because that project was the biggest inspiration for me to sell things for the price of the actual thing, but I misread somewhere that Claes Oldenburg, when he did his ‘Store,’ he sold things for the price of the actual thing. So I was imagining him selling the plaster 7-Up sculpture for, you know, 75 cents, whatever. But last year I actually got a book that was self-published by him that detailed his entire store project. And I found out I misread it a year ago because he had a price list of everything and he definitely did not sell things for the price of the actual thing. So I don’t know where that came from, but that kind of misreading was really a big component of this project. Even up to now, I’ve done a few other projects about copying market pricing and even though now it’s a realization, like, “Oh man, I was wrong for five years,” I still want to honor that method be cause I feel like I’ve made something more interesting out of false information. <laughs>.

Oh, absolutely!

I guess another important part of this project is that it’s been done quite guerrilla in the past, as my previous professors would describe it. Like, I show up regardless of if people wanted or expected me. That started off with the Davis one actually, because UC Berkeley didn’t participate in CCACA [California Conference for the Advancement of the Ceramic Arts] in an act of protest against the folks that ran the conference.

We hadn’t participated in quite a few years. So for a decade, I think, Berkeley did not show what their students were making. But I was just getting into ceramics and I wanted to do something, but I didn’t want to go against my department’s protest, so I was just like, “What if I just show up?” You know, no official notice, no real connection to the event aside from I’m there, no one’s gonna know who I am or any associations. That idea of just showing up and thinking of it as a protesting performance is really what compelled me to go. I mean, I’m so introverted in the sense that I don’t really like interacting with people that much.

Plus, I don’t like the idea of making a spectacle of myself. Looking back, it’s like, “Who the hell convinced me to go out to Davis by myself, put out a stand, set it up and try to sell ceramic food to people walking by who might not even know it’s ceramic and think it’s just a silly plaything rather than fine art. But I did it and it was, without a doubt, one of my favorite things I’ve done. And I found out that it’s just really fun to pretend to be a businessman. <laughs>

The backdrop for the photo of you at Davis shows you before a series of signs of actual businesses—“The Halal Guys” and “Pizza Bar”—directly behind you in this strip mall setting is amazing. Even just the position of the camera where you see (in the top image) an adoring public of this ‘street-side market’, a kind of lemonade stand and the other shows the guts of the performance. You with the wheelbarrow with your artwork. You might never know you’re introverted like you said, and that you don’t like to interact with people. At this point in the project (the third iteration) were you beginning to notice changes in the performance aspect of it? And kind of learning to perform the work in some way?

The first time I did it was at Berkeley. It was on campus and near the art building, so I felt like there was a kind of security there where people could be like, “Oh, he is an art student” or whatever. The second time I did it in San Francisco at the San Francisco Art Institute for my professor Whitney Lynn who was having a show. And she was like, “You should bring that project you’ve been working on” because she saw what I was doing by using all my studio courses to make components for one really big project. So I brought it out but it just didn’t work really. And I wanna say Davis was the one where it really kicked in.

I felt like Berkeley and San Francisco were very lax. I felt like I was too comfortable because I was around places I knew well. Davis was the first time I went to a place and it was really just me out there. The school wasn’t there, the professors I knew weren’t there. So it was me setting up and it was this mindset of: “No one knows who I am, so it doesn’t really matter.” <laughs> And I think for the performance, I was taking cues from the year before when I did The American Dream/Renny’s Delicatessen. I worked for Vallejo’s oldest ice cream and candy shop.

Yes. At some point in learning about your work, I learned that and followed up. I looked it up online and came across some photos. So I have a sense of what it looks like. And when I left Napa a month ago—from that recent mural project—I thought, “Oh man, I wish I’d gone to the old ice cream shop!”

No, you shouldn’t have! It’s changed owners and they don’t make anything anymore. They just get things shipped to the store and they sell it from the shop. The magic is gone. I mean, I had mixed emotions about the place because of the way that the owner was and all that stuff. At the same time, it’s a complex thing of the appreciation of the homemade craft of ice cream and chocolate all made by hand and in-person. I think that appreciation for the handmade was something that resonated with me. And there was one time where the freezer door was left open and all the ice cream that was stored in there just melted overnight. And the owner had a standard despite having so little ice cream. He was hard set on selling only what we made by hand, even if it means like we’re only gonna have one gallon a day. And I appreciate that. And it’s just such an appreciation of the handmade and being there, making the chocolates by hand, making candies by hand. It was an understanding that a lot of work that goes into production of “simpler pleasures” like sweets.

You were beginning to talk about how learning and engaging with the performance itself is related to having worked at the ice cream shop and that learning how to make things by hand influences your approach to making ceramics. But you had said in 2016 that was your first ceramics class?

My first ceramics class, yeah.

But you had been making handmade chocolates at the ice cream shop around that time? Or when was it that you worked at the ice cream shop?

My time at Liled’s Candy Kitchen was after my first ceramics class but before I started ‘The American Dream/Renny’s Delicatessen.’

Being told that what you were doing was a guerrilla tactic of some kind, were you thinking about it that way already? Or it sounds more to me like you were following an impulse and then people were noticing such an approach? I feel this happens a lot of times, you know? A very organic practice motivated by personal research and reflection and then by asserting your own voice begins to be categorized (or named) for what you’re doing. How did that land with what you were doing? Were you thinking, “Well yes! This is guerrilla work!”? Or was it becoming more social commentary naturally? What were some of the ways you began to think about it the project as people were naming the practice?

For a time I did consider it ‘guerrilla’ and on my CV I did put up a ‘popup/guerrilla projects’ section. That’s because it started off with going to CCACA, but then there was a time where Renny’s Delicatessen would just show up at openings. Like, there’s that image that of me holding a box and that was ‘The American Dream/Renny’s To-Go.’ And that is when I would be able to go to galleries in San Francisco on opening nights and show up and just stand outside the door and sell ceramic food to people going in and out. And most people were like, “What the fuck is going on?” because it was almost always not relative to the gallery I was doing this stuff in front of.

<laughs> This is the slide?

So that’s where the guerrilla thing came from because people started realizing that I was just gonna do this no matter what. And I was like, “Well, it just seems like a thing I can do.” And, you know, I started off doing the Renny’s To-Go outside galleries because I got rejected from a group show and so I was like, “Okay, yeah. It’s whatever.” And then I went outside the gallery for the opening night and I was just there in my uniform, holding a box of ceramic food.

I mean, that speaks to your agency! I hear that very clearly in what you’re saying: the agency in just showing up and saying, “You know, ‘I invite myself! I belong here!’” But also you did it with such a strong sense of humor, too. To me, there’s a real performance of dissidence and protest in that. So do you think that that critical stance of the art world (dominant Euro-American and capitalist culture) emerged totally alongside the work? That deeper social critique of what work gets worshipped and chosen, which I know relates to your artist statement, and where those invitations come from? The gatekeeping of the art world and all that. Is that anything you’d like to talk about?

No, for sure. That’s such a big part of it. I mean, this project started off as a sort of protest. The project actually started off by me just being interested in sculpture and then being interested in Asian Americanness and Americana. But then I think when it came to like the installation part of it, then it was all about the social practice part. I want to say the first time that I truly, truly cared about where it was and it felt like the project was real was that Davis one in 2018, because there was an importance of being out there where I wasn’t technically allowed and where I wasn’t expected and sort of disassociated from the entire event, but yet still have this uncanny thing of association because I had ceramics.

And also, this protest was in line with, “What is a fine art object?” Because I was selling all these things and people could walk away with something handmade by an artist for $2. And there’s multiple avenues that people have taken in the past where: is the artist being exploited or is the public being exploited? But whatever avenue it is, it is always about the expectation of the cost of art, the expectation of the cost of food, and all this stuff and how that is very different everywhere because the cost of living changes.

Before Davis, I searched the places in Davis that sold artisanal donuts, artisanal cakes, etc. And I did it for three years [at CCACA] before I stopped because the conference started to ask me to actually be part of it and be inside the main gallery and I said, “I’m good.” But I had to realize that I had to stop this now—I saw that they were benefiting off of this too much. And so I stopped it there at that conference. And then I guess that was good timing because after that, Renny’s Delicatessen’s tenure at West Coast Craft began. It’s this big craft fair… I’m trying to find a way to describe it…it’s a very beige fair.

I wanna thank you for introducing me to this word. I don’t know if it’s just a cultural blindspot for me. But geez, beige! Everything that you say about it to me signifies this kind of whiteness and this kind of over-aestheticization of what’s comfortable and neat for people. Like when I hear ‘beige’ I just think of something that’s been really normalized. Where does ‘beige-ness’ come from for you in the decor world? But also, how does it relate to the marketing of something that is ‘nice?’ Like, what does beige mean to you?

I mean, I hate to say that it’s a beige fair. Like, it’s such a neutral thing because in terms of fashion and clothing, beige is pretty damn good. It’s like you go down almost every aisle and it’s all the same color everyone’s trying to exploit. Like, they’re all trying to say something with that kind of cleanness, that crispness, that kind of neutrality as like a statement. But when everyone’s doing it, it just all blends together and it ends up becoming almost bland or blank overall. Like, you get lost in the beige.

Yes. Bland, beige. I’m seeing how the project evolved from setting to setting. And that the influence of context seems, you know, inevitable. This layering of where it is experienced and who is doing the purchasing and where the invitation is coming from. Again, I can see how your work is motivated by this kind of culture jamming, with the possibility of you playing the trickster. So at this craft fair, is that idea also a part of the work? And how do you talk about that?

Yeah, 100%. I started off at West Coast Craft because they were taking applications and I applied with a very honest application and I was like, “I am applying to do a conceptual project called the American Dream/Renny’s Delicatessen. This project will not make money. This project is selling things for the price of the actual thing.” And West Coast Craft replied back and was like, “I actually really like this. I think this would be a fun thing to add into the fair.” And the director added me to the LA roster for later that year.

I spent a lot of time looking at this picture. So that’s LA there?

Yeah. So West Coast Craft said yes. And I’ve been to West Coast Craft before and I’ve sort of decided—based on that experience of going around—it’s an extremely white fair. Many vendors are white. Many of the people going are white. The things for sale are white or off-white or beige a lot of the time. And so in my mind, for West Coast Craft it was, “I gotta make this an annoying ass tent. I HAVE TO make this an annoying tent.” So, you know, lo and behold, here comes install day for West Coast Craft LA in September 2019. I am, like, one of three people out of 100 or something like that with a colored tent, let alone it being a bright red striped tent that looks like it belongs in a circus.

And I could see it from the parking lot <laughs> because it just stands out so much that you look down in an aisle and it’s of course one of the only splashes of color and that’s me. So it was really funny having friends in LA saying, “Where are you?” And I’m like, “You can’t miss this. You can’t miss this striped tent.” And they’re like, “Oh, okay,” and they do find it very fast.

And not only the striped tent, but there was also striped tablecloths, striped aprons, striped name tags, like a lot of clashing going on cause every set of stripes had different widths cause I didn’t think a standardized width was important. But there was also this aspect of, you know, you go to this craft fair, and a lot of times this kind of accessibility of the ‘craft’ at the craft fair is starting at very expensive prices. You know, they’re free to attend and people go and they expect this price. There’s a lot to it and it’s a very complex topic because at the same time, I understand and support the price of craft.

I understand the price of an object, but a lot of people are within lifestyles where it’s just not possible to have that kind of affordability. And so with this project, I appreciate the fact that I was wanting to sell things for $2 to $40. I think the most expensive thing was the cake for $60 based on the price for a small cake at some fancy cake place. And it was great because people were going to the craft fair and leaving with something—they were leaving with art. Being able to take home a piece of art, have that conversation about this thing being art or being craft or even being like an art object since the project itself seems too goofy to be “fine high art.” But, you know, it was a great thing to see people go in and reach into this pile and find what they want under the expected price of an upper-middle class craft fair.

I’d like to share with you that we may have some overlapping experiences from my younger work life. I worked in kitchens in high school on Martha’s Vineyard and I worked at a flea market, as a vendor for a woman that had a small clothing line. And I spent a lot of time with other vendors at the market and artists at artisan’s fairs. And I also worked as a baker in San Francisco for three years. And from my experience working in the Bay Area, I feel like the (fine-dining) food world has a very comparable dynamic to the fine art world in terms of, you know, labor and exploitation and what gets to be expensive, not expensive, valued, all of that.

Anyways, I’d love to hear more about your experience in Los Angeles. You were saying that you brought the project further away from familiar places and people that by the time you get the project to Los Angeles––to these very ‘beige’ fairs—there was perhaps a catering to an elite scene? I’m curious to know more about what the representation is like in terms of the cultural identities and even the practices of the vendors themselves? Are you saying your experience of it was also White and beige as in there was not a lot of BIPOC representation? Is that also reflected in what you’re saying? Or is it just like it aesthetically was very white and bland?

It is also slightly reflective of vendors as well in the sense that a lot of them are white crafts from white artisans. And, you know, West Coast Craft actually does a good job about this in the sense that they have scholarships for free booths for BIPOC people—I think that’s great. They have two reserved, every single fair, for BIPOC and two reserved for women who want to go to the crafts fair and have the $800 booth fee comped. The folks that are there and able to consistently show at West Coast Craft, they have that kind of financial stability. And I feel like when I go to a big name craft fair, I feel like I see the same booths around and I do notice that there is a kind of trend of who are the folks that are able to consistently be at every single fair and even go to the one that is hundreds of miles away.

Right. Thanks for sharing that. Because I’m aware of how these situated dynamics of whiteness and systemic institutional power can create blind spots around accessibility and the privilege that exist in institutions (here in New England) and also in relation to my own whiteness, class, and ability privileges. I maintain a focus on ways to bring these ideas into dialogue with the curatorial and education work I’m a part of, always being very keyed into these questions because of my education and coming up in a family culture that has critical views of American history. As in, so much of what was handed to me about American history was really through a critical lens around the origins of this place.

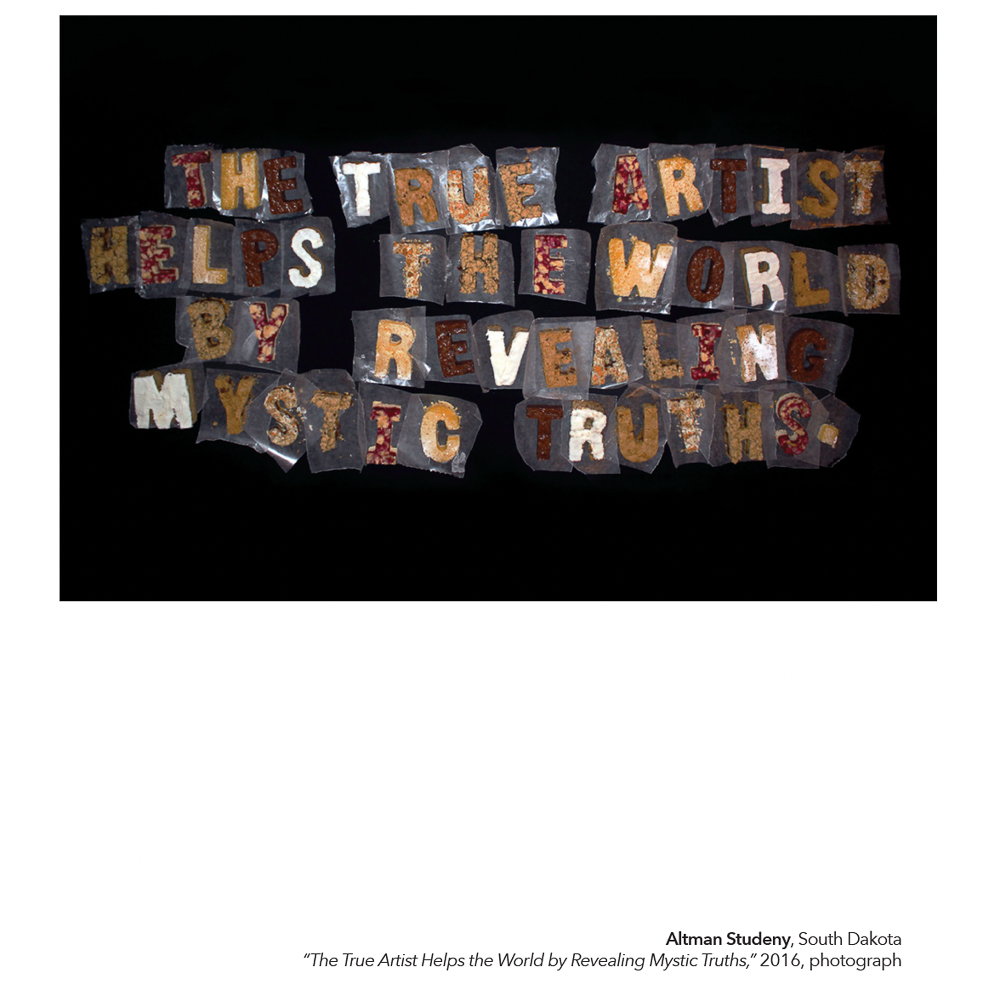

The complexity and ethos surrounding your Renny’s store project and its production contains so many of the aesthetics and rhetorical strategies I’m eager to platform and focus upon with Hole History Show. I first hosted Hole History Show here in Rockland, Maine in 2016, and as a curator and as someone who’s interested in restorative practices, your work touches deeply upon several ideas that I’m most interested in cuing up for people to pay attention to. I’m really grateful for working with you and being able to really have people have a more extended look at these dynamics that you’re sharing through the work. I deeply appreciate how you recenter and flip the critique back at the places by being an artist, showing up, and holding your ground about it being a conceptual project and critiquing it from the inside. It’s so brilliant.

Thank you. That means a lot. It’s really funny because you were saying it is a complex project and the funny thing is I never expected it to turn out so complex. It was sort of just, “Let me make ceramic food and sell it for the price of the thing,” but I think with every iteration, things got more complex and I’m sort of understanding my position in the project and what the project can do. So it’s also nice to reflect back on that rather than just, “Oh, this is what I did last time.” Looking at it by stepping back at the expansive view and looking at how I’ve done it every single time and it’s nice.

I appreciate your realness in saying the project has changed from where it started. I find many creatives can be attached to talking about project evolution like, “I knew what I was doing all along and I set out to do it just this way.” And of course it’s so human—and I really operate from this place too—where the process of making the work is in revealing itself to me as I’m going. And if I’m staying really authentic about the questions I’m asking and if I’m keeping it open-ended, I’m learning so much. I feel the process itself more materially so the depth of conceptual terrain can deepen. I recognize this is the rhetoric or the line of questioning that emerges in your work because of just how it seems you were reflecting upon it with each setting and audience. And I’m hearing as you’ve gone through the project’s chronology–––well, it’s affirming for me, how gracious you are with yourself to say, “I’m figuring out where I can take this, where can I push this?” What was the last place it was installed before Portland?

San Francisco. So the slides that you were seeing of the photo of the bright red tent is in San Francisco.

Got it.

And so it was there last and I think around this point, I started thinking of the conference at Davis differently. I was there for three years and people started expecting me and they started loving for it to be there, but mostly for their conference. And then I was sort of like, “Yeah, this is sort of getting icky, I’m outta here.” And I felt like experiencing that in San Francisco another time. I think that might have been like my fourth West Coast Craft [note: this includes West Coast Craft Markets]. And after that, it just started feeling like I got absorbed into a kind of craft fair vernacular rather than people taking in the project and trying to understand all the components, or at least a component that would bring them into the idea that this is not just a craft booth, but a conceptual project.

People started asking, “Are you gonna make any more ceramic food?” and “When will you make some more cakes?” It started becoming this whole sensation of ceramic food—which is fine. And that was a part of the project itself, this kind of play on picture-perfect Internet food and also picture-perfect ceramic food, which was and is a really big trend. And at the same time, it’s been hard and weighing down on me that people are very obsessed with just the ceramic food and they don’t care that this is a fake project about fake Americana, about fake history being pulled out from seemingly random but actually intentional stuff. So I think after this I started getting tuned down and I was thinking I can’t do West Coast Craft anymore because I feel like if I do it, then it’s sort of contrary to the actual project itself. And then people are gonna just go for the ceramic food rather than like this crazy thing.

Gosh, that makes so much sense, right? If the critique is somehow being overshadowed, it basically starts to undermine the foundation of the work and the motivation from the start. And I also hear that it was beginning to feel like that participation could be exploitative? Which can happen with grassroots or guerrilla projects the moment that it becomes something that other people benefit from, which you just articulated in some way. Basically, in saying no, you exercise agency and control over what the project is about.

When we had a moment to connect before organizing to bring this work to Portland, I was made more certain how the underpinnings of your work were aligning with the foundation of the Hole History Show. As far as what I saw myself trying to promote and share dialogues around ‘fake histories’ And also, the social and political climate of the last 10 years. What are some of the things that made you say “yes” to bringing it to Portland, Maine and to the East Coast?

Well, it was just like, “Why not?” In the sense that it’s Renny’s Delicatessen, it’s always been about being at a different location and using site specificity as a part of the project. I felt like after that 2021 West Coast Craft, I can’t do this at a craft fair again. And it was sort of crazy to think that because other large craft fairs were asking me, “Do you wanna do something?” it was this overwhelming feeling of knowing they were expecting the striped tent and I don’t wanna pull out the striped tent for a while because I feel like now it’s just been subverted into something that it was never meant to be. It was subverted into the thing it was critiquing, which was my moment to go, “Oh my God, I have to stop this.”

I felt like it was okay going to a place that was unknown to me, but also allowing this kind of weird shift in the sense that I didn’t expect to be there and the project was gonna be there by itself. It’s gonna be in a window display, which is different, and it was a delicatessen display, so it’s worked for me. I felt like it was also a great avenue in terms of selling. Julia did say she was gonna be able to sell them on the next art walk, I believe. For the July art walk. It’s interesting in terms of that, too, if we’re talking about selling in the sense that we’d be charging prices for them that reflect Goldbelly’s pricing.

Tell me about Goldbelly.

Goldbelly is a food website and you can order food from famous restaurants across America to other places. So I found all the things that I made on Goldbelly and priced them as if they were getting shipped across the country, which they did since I made them in California and shipped them to Portland, Maine. So things are dramatically more expensive and that’s still talking about the cost of something, the cost of labor shipping, all that stuff. So I thought it was just an interesting avenue to go down in terms of in the whole history of the project.

It’s brilliant. In terms of the project’s chronology, it’s such smart and responsive work. Responsive to current market consumerism and responsive to the up-to-the-minute-market ‘value’ of consumer goods. And also highlights what is the market—what’s the word—from 2016 to now…

Trend!

Yes! The marketplace too! That’s incredible. So Goldbelly is not like the regional ‘what’s next door. I’m doing this on the lawn of UC Davis!’ It’s what the national market is. Gosh! That is brilliant. That’s just right.

I love the window installation and I loved how it’s been set up and I love everything about it, but I think it’s the end of Renny’s for now, at least a little bit.

Can you tell me about what it means for it to land on the East Coast? And perhaps what it means for it to land in a window installation that is squarely an artists’ exhibition space. You’re not there in the tent. You’re not there to tell the story. I documented my installation of the work. I did various things to document this installation and I was approaching it in the role of the archivist. Because, I thought to myself, this really speaks to where the work is right now, on view at SPACE, which is right next door to Renys Department Store. There was a level of confusion that people has that lent itself to a high concept, kind of circular logic, which I’m always looking for. I think it’s an incredible place for it to land in terms of the consumer’s relationship to a storefront gallery. And now pricing the ceramics based on Goldbelly is so responsive to the dynamics of the art world, the dynamics of the market, of food and accessibility. This is such an incredible project. I already love it and now I LOVE it 10 times more! <laughs>

Yeah! I think it’s also nice that it went to the East Coast because when I started the project, I was very early in undergrad and I was sort of just…I didn’t know what being an artist would be like. Now, it’s years later and I’m getting the kind of shows and opportunities I’m getting and I didn’t expect this at all within five years, even within 10 years. I didn’t expect any of this to happen the way it’s progressed. You know, now I’m working on expanding from just the Bay Area, and outside the West Coast for that matter. I’ve got a solo show in Boston in December at Praise Shadows Art Gallery. I’ve had artwork in New York City. I’m in talks for a show in London next year. I feel like going to the East Coast makes sense for a grand finale because it feels like I’m going places now.

It’s almost like the opposite of the Oregon Trail. I feel like a lot of West Coast artists feel like once you get into shows on the East Coast where it’s more central to the entire Western art world, then it feels like you’ve made it and are going places. <laughs> That’s a bit extreme, but it sort of feels like that as someone who never expected to be an artist.

Yeah, absolutely. Let’s talk about your other recent store-esque projects and the recent work at Catherine Clark Gallery.

Oh, the Museum of Found Objects.

Yes. Museum of Found Objects. Would you like to talk about closing Renny’s Delicatessen and the progression of the work and what it says about how it relates to these other directions that you’re going? How do you feel about the work as it enters into gallery spaces? And in the interim, where is the work from Renny’s Delicatessen going to go, aside from whatever doesn’t sell on GoldBelly? Will they go into storage and be available to loan to museums? Can they exist as museum objects now and can they be separate from the performance?

I mean, they can be. I don’t see why not. It hasn’t shown up much as an opportunity yet. In fact, I think this project itself is just such a weird project for galleries, too. That’s why I’ve been just doing it on my own and through other venues. Galleries love it in the sense that, like, it’s a fun project, but they don’t love it in the sense that this is a project that’s guaranteed to not make money. This is a project that is guaranteed to not be a breadwinning thing because everything’s priced so cheap in terms of art. I walk away with, you know, $2,000, but $2,000 doesn’t cover the labor for making nearly 1000 objects and all the electrical for the kilns and all that stuff.

So, it’s a very funny project in the sense that it is self-destructive. <laughs> I think in terms of museums, I have a big idea. So, Renny’s is gonna take a break for now, but I think in the meantime, this project will always have a special place in my heart. And I’m going to be making relic videos, sort of like how McDonald’s would have old employee training tapes. I think that’s where these works and paraphernalia will come in and the actual objects from the project will be props for video work and all that stuff. And then ideally in the end, I wanna take this to the next extreme. Since I’m working with more concepts of my store projects and stores, establishments, faux businesses, like the museum and all that stuff, I think in the end, I wanna find a way to make this project act very similar to franchisees and franchises for institutions and museums or wherever.

Like, a museum can “buy” a franchise and when they buy a franchise, they get a box that’s full of employee training video tapes, uniforms, things like that. And that for me would be the best representation of the project within a museum context. Because there would be objects that are a type of faux memorabilia, but at the same time, the pressure of the ceramic objects themselves are not there for me as the artist. They’ll have training tapes to make everything and make it up to the original project goal. I think my dream would be if a museum or institution does eventually makes the full commitment and make people watch the training tape and make all the ceramic food the way that I was making and glazing it, and to see them have their iteration, just like how if you’re the owner of, I don’t know…like if you’re higher up on the Subway chain, you go to a Subway and you see how they make the sandwiches there, you’ll have your visions of what you’re expecting, but when you go they might be different.

So I’m hoping to have that happen in the future. And it could be, you know, a few decades from now. But, I ideally want this project to sort of be encapsulated this way. And I think, in the future, I think that would be the best way to remember it in terms of this goofy project that did have a critique in all this stuff, and it lived on in so many different ways, and it felt like you had to be there to really know what the hell even happened.

Yeah, there’s just so many expertly crafted opportunities to not miss the point. That’s another point: I feel that the art world can be so coded in how it talks to the rest of the world about what it’s doing. And the life of a project like yours provides opportunities for people to say “Well, this was at work all along!” To use those devices of humor and satire embodied in the craft is such a skill. It’s evidenced in all of the ways that you think and talk about it and also knowing where it could go next. It’s an incredible representation of just letting something evolve as an instructive element in developing your practice, your protest.

Okay, last question! Of course you’re saying the project is goofy and intentionally embraces ‘ the caricature’ and other mechanisms of performance art and a level of societal critique. The ways your sculptures mimic original objects in this stylized way creates access points for people who don’t know how to…when they see this thing that they might think, “This seems hokey! This seems goofy!” But to really then slow down to look at like how the materials were handled with such a high-level technique, it’s almost invisible to people because it looks so much like the real thing to be a caricature! I just can’t say enough about it. The cakes for example? They’re not just a copy in the way that you’re saying people are seeking on the internet with hyperrealistic ceramic foods trending on the internet! Yours contains a whole another realm of excellence because of the way you’re subverting the use of techniques in the ceramics world to create something that’s not just perfect, you know? <laughs>

You know, me and my friends were talking about the kind of allure that the projects have, specifically the fake stores. I was saying how I think it’s because there are two avenues that people go on: it’s a conceptual project using representational objects, so people love it for the conceptual thing and people love it for the representational thing. And sometimes people love both. When I first did this project in 2018, half of the objects were all ceramic and half of them were ceramic and oil paint.

I was taking painting classes and I was mixing oil paint with cold wax medium and making it as bulky as possible and spreading it on ceramic cake slices, like real cake. And so this obsession with that came through and eventually, maybe a year later, I looked at a slice of cake I had that had oil paint on it and it aged pretty badly because that’s what happens when you mix cobalt dryer with a cold wax medium and let it out in full sun. It just ages very gnarly. Which for me is fun most of the time, but something felt off about it for this project. I gave it to a friend because I was like, “I can’t live with this, but if you want it, you can take it.” I think honestly, in the whole span of the Renny’s Delicatessen project, I think those first pieces that are oil paint and ceramic are probably the most fun because they were made at a time when I really didn’t care and didn’t think about them. But now there’s like this curse of thinking about longevity. And so then I pivoted over to all ceramic, but I still kept all those techniques that I was doing the same, even though the medium is not the same and the medium does not behave the same. I was still using piping bags and squirting them out and I was still using actual baking spatulas and spreading things out that way.

I can tell! <laughs> I can tell because I made so many pastries over the years, but I don’t know how to work with clay. So, I want to thank you for giving me some objects that allow me to talk about the methods and skill that goes into making these look so hyper-stylized in a way that I think is so accessible. I didn’t know this before setting out to work with you, but I also found I was getting to a place (with HHS) where I thought, “I’m not doing the donut show installation again.” I’m going to take a few years to catalog it, apply for grants to document artists who I’ve worked with (2016- 2023) and also document the ways that I’ve participated/performed the work on some level. Hole History Show began as a way to create exhibitions that would become a printed archive and to illustrate how people find their way to the project and how they respond to the narrative and to the claim of the hole-in-the-donut-invention being singularly marked (on a plaque), near to where I happen to live now. To say the hole-in-the-donut was invented here!?

There was a regional donut festival last weekend! I’ll send you a link to the public access station covering the festival. That’s also got to be a part of the archive of the project. I’ve now participated as a donut taster, I’ve participated as a donut expert, I’ve participated in all these ways and all the time I’m saying I’m an artist and I’m a curator and I’m the collector of the things that come through the show and curatorial project. I kind of feel like I arrived at a place in the project where I have to think more about what happens if and how it becomes performative for me. What I want is for people to see me as the collector and the archivist who’s giving an artist talk about how we talk about ‘Americanness’ as an adjective.. not representing a “Donut Historian,” however much I know about them now.

So for now, the Hole History Show is also ending with Renny’s Delicatessen/The American Dream. You’re the last installation, for now. To sink into it and think about what can this project really continue to be about?

It’s a nice kind of meditation point for the projects in the sense that they’ve both been very cumbersome to their own degree and I like what you were saying where you want to ask yourself, “What is this project about?” Because it feels like this is the end, but it’s not. It’s just the end for now, in order to make one last or a few last iterations where I’ve honed down and am looking across the span of six years. Six years is a lot of work.

Looking through each iteration and being like, “Yeah, what is the takeaway from here? What is important here? What is this?” And I like this interview because it brought up a lot of that through the early projects. Letting me reflect with you about what was great about that and what I did next year and so on. I am sad, too, to end the project. So are a bunch of people that I know and folks that I’ve met from West Coast Craft and the multitude of collectors that got to know me beginning with fake food. I love them each to death and they’re great folks, but a lot of them gravitate around the ceramic foods and not the project at all. But maybe that was the point of Renny’s. A succumbing to its own critique.

I feel like it’s also okay to call it quits because I feel like so many great artists I admire, like Joan Brown or Robert Rauschenberg, when they had a project and they see the apex or the start of the fall, they’re like, “End it now.” They end it and it feels like that’s the benefit.

Yeah. I agree. And I think giving it an end. It also gives it more value to the project to build in that time for reflection. To pause the pace of work life, artistic and creative work in the face of an attitude of ‘more is more.’ I think there’s more abundance for me in actually closing or stopping so that it can steep in. And reflect on the settings where I gave the talk or the exhibition happened and where or why has it still not landed? Where people didn’t know why I was there or didn’t understand why I was using this as a platform for critique.

Oh my gosh, this has been such a good talk with you. I appreciate the opportunity to hear you tell the story of the Renny’s project from the reserves in the bag of clay student days and that curiosity and sharing the evolution and impulses, pressing the questioning, and the reframing has been incredible. Anything you’d like to add?

No, I feel like we’ve discussed so much and I feel like when I make those employee training videos, I think I’m gonna have to go back to this interview, too, because I feel like there’s just so much that we touched on, even things that I didn’t even really think about. It’s been great. And I’m very excited.

<laughs>. Great!

Installed in the Window Gallery, SPACE, 538 Congress street. May 1st- June 20th 2023

The American Dream/Renny’s Delicatessen (2017 – 2023) is exhibited at SPACE as a part of the Hole History Show: Origins of the American Style Donut curated by Alexis Iammorino.

This curatorial project began in 2014, as a personal inquiry into ways that my work as a community artist could more assertively combine my interests in interdisciplinary, collaborative research models and, in an idiomatic fashion, from the field of public history. I’ve remained, particularly in these recent times, how it is that false, misleading, or bombastic claims (of all kinds) can prompt cultural and societal critique of how knowledge operates in a relational space between faith and fact? This curatorial project continues to be driven by an interest offers a conceptual terrain and an inclusive venue for discourse between the dynamics of belief and fact, the forces of capitalism as well as the implication/significance of American as an adjective.