Norwegian artist Jenny Hval brings her haunting, subversive experimental pop to SPACE tonight. It’s full of ideas, doesn’t sound much like anything else and will easily get stuck in your head all day. She generously agreed to talk with me from the road—there was a two hour break between the first 5 minutes of our conversation and the rest of it when she lost reception driving through the Adirondacks. We talked about her obsession with karaoke, being drawn to extremes in music, undressing onstage and stereotypes about women in the music industry, among other things.

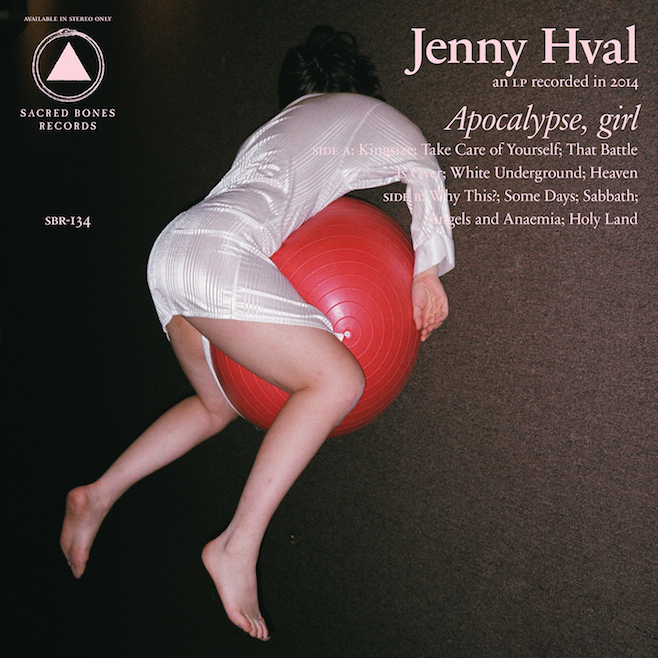

Can you tell me a little about your upcoming album, Apocalypse, girl? What were you thinking about while you were making it?

I was thinking many things because it took a long time, it took like 2 years to write. What I’m saying now in this moment is my memory of what was happening, which tends to change a lot. I know that this is my least eloquent phase of doing interviews. Bit interesting for you! Because after a while I kind of memorize what was going on and at this point I’m still trying to remember. It started out with…well let’s say it started out with, as if I’m telling a story…with me getting really interested in karaoke. The performance of it. Not so much me starting to do karaoke because I’ve maybe done that twice in my life. But more like enjoying certain performative aspects of karaoke. People really using it as kind of an emotional, I don’t know, catharsis or outlet. And then also the element of trying to be someone else, trying to take on some famous voice, which I find very fascinating and moving. Not in a professional way, but trying something and maybe realizing mid-song that, oh my god, this is impossible or that you’re not a good singer. These things, normal people performing. So I was watching a lot of weird performances on Youtube and then I started writing on top of different backing tracks, anything from a sound to a beat to someone else’s song.

Where do you find backing tracks?

Anywhere, they can literally be anything, like just standing in a room with a lot of noise. So yeah, I can be quite obsessed with very normal things sometimes.

You sing in your second language, right? Is there a reason for that?

There are several reasons. I think I wanted to write in English because I moved to Australia to study writing. So that was back when I started writing, but also I grew up with music that was almost entirely in English. Norway’s a very small country and we haven’t had the biggest music scene, so for somebody who really wanted to get out, get away, it was very natural to get away by perfecting another language.

Do you think differently in Norwegian vs English?

I used to think I did. But maybe it was more sort of something I wanted to feel instead of an actual fact of behavior. I think I tried to say the same things, but I learned that I definitely sing very differently in English. I tried to compose with Norwegian lyrics, and I realized that I had to sing in a tone of voice that reminded me of, like, Indian raga singers. That was the only way I managed to feel like I could sing lyrics in Norwegian.

And you do a lot of interesting stuff with your voice, so did that kind of feel like a limitation?

Well, I think language has definitely got something to do with a certain freedom of going beyond words and the meaning of words, so I think that’s been liberating, allowing me to explore a bit more vocally than if I’d been using my own language. But I also think that, again, because there hadn’t been much music with Norwegian lyrics that I could learn from when I was growing up and it was mostly singer-songwriter music, very straightforward, somebody singing in a very plain tone of voice. So yeah, I always looked to the outside.

You’ve said that you’re drawn to extremes in music. Does that include how you make music?

No, no I’m not a very extreme person I would say. I mean, I don’t know what extreme is, I guess it depends on who you’re talking to. But when I say extremes in music, I probably mean that I like very loud music and very quiet music, and I also appreciate everything in between, but sometimes I’m really drawn to a certain type of music and I get really into the details of it, the fibers of that music. So I could get very much into something extremely loud and spend a lot of time with that and listen to it over and over and just really kind of see what the thought in that loudness is. You know, like when you’re in a room that has a very specific soundscape—like if you go to an office every day, the sound of it is going to be a big part of your life. So I like to go into worlds of quite specific types of music as a listener and get very nerdy about it. I guess that’s what I mean by extremes. Not so much about how I practice music. I wouldn’t say that I really explore extreme things when I sing, because I’m not an improv singer or a trained singer. I’m not very much into technical stuff, I’m more into emotional layers I guess. And I’m also like that as a listener. So it’s more about how I listen.

I was reading an interview with Bjork recently where she was talking about how frustrated she was that she didn’t get credited for her own producing, and I have female musician friends who talk about men, well-meaningly, telling them how they’d improve their music. I was wondering about your experience with some of those assumptions about women in the music world.

I might have been quite lucky. I’ve worked very independently, I haven’t been in the industry, I haven’t even had collaborators on the practical side of things until recently. So I’ve been allowed to do my own thing. I’ve produced an album on my own and yeah, I’ve been allowed to develop what I do in my own way. But I’m very aware of how people are quite uneducated about what happens behind the scenes of making an album and of how things tend to be a bit gendered. You know, like the stereotype of the female artist in the male producer’s arms, held safely by the male person in the background who’ll be organizing and saving everything, doing all the technical stuff. But it hasn’t really been in my world so much because I’ve been a little bit out on the outside. I have had my share of interesting reviews, where I’ve been called various things because I think that my music makes a lot of people uncomfortable and they respond by putting the blame on me.

What have the reviews said?

From very early on, I guess I’ve been told by many reviewers that I have hang ups— like sexual obsessions, trying to provoke, these kinds of things. They’re not taking seriously what I’m saying, that it has anything to do with society or philosophy or existential things or anything. It’s easier to just call it ‘sexual’ because you can always take something made by a female artist and label it sexual. Like if you undress as a female, it has to do with sex. Whereas if you undress as a guy it can mean so many different things, and even if it does mean something sexual, you retain power in a way. Like if the frontperson of a male band is naked on stage, it can never mean the same as naked women onstage. I’ve thought a lot about these things, but I haven’t been exposed to the big media attention. I’ve kind of studied them from the outside.

With someone like Bjork, she would’ve heard from so many reviewers over and over again that this person made the beats, that other people did it because they’re male, and I know that it was really important when she finally said something about it a few years back. I think these things need to be written about because well-meaning listeners, with no agenda at all, don’t really think about these things. These stereotypes need to be countered and they need to be countered many many times until people actually don’t think about them anymore. It’s like a slot machine, you need to put so many coins in it.

What are your novels about and have they informed how you make music and vice versa?

That’s a hard question. I think my novel is too non-narrative to really be about something. I‘ve written one novel which is more sort of theoretical and poetic, very tied into song-writing but also exploring a lot of feminist theory from the 70s or early 80s and trying to put it in a more contemporary setting. That’s one of my books, but I’ve also published a book that’s more about music and performing music. It’s more like essays and that is, I think, a lot closer to what I do musically. So they’re both little books, easy reads, not meant to be big books. They’re kind of meant to be read like an album.

Your music videos are so beautiful and striking. Did you work closely with Zia Anger, who made the video for Innocence is Kinky?

She’s on tour with me right now! She’s on stage, she’s amazing. It’s the first time I’ve had a video performance band member, she’s really playing with us. So at the moment we’re touring with two of us playing music and then one of us playing video and performative stuff. I think it’s gonna be a great combination but it’s the very early days of this approach. So it’s a very exciting and vulnerable time, live. I think it’s probably a very interesting time if people are curious about seeing something that’s out of the ordinary. It’s a time when everything is quite innocent in that collaboration.

So is she improvising? Does she have a bunch of images and she responds to your music?

No, it’s much more simple. We’ve got a small screen on stage, the size of a human, and then we’ll have other elements too. But it’s still kind of changing, and our ideas are changing every night.

(This interview has been cut down and edited slightly for clarity.)