Surabhi Ghosh is a Texas-born, Georgia-raised, Indian-American artist, professor, and resident of Montréal, Quebec. Her current work investigates the transmission of culture to diasporic people, specifically South Asian immigrants and their descendants in North America. She uses textiles, patterns, and site-responsive installations to materialize contradictory narratives which begin and end in her own experiences. She was an artist-in-residence at SPACE from August 11th-25th, 2017, where she was grappling with the relationship between her ongoing historical research and her studio practice. Garlanding and Guise will be on display in the SPACE Window, overlooking Congress St. from August 25th to October 22nd, 2017. Her residency included an artist talk, “Now to then, there to here / Then to now, here to there,” where she discussed her work as part of an impossible quest to understand what it means to be a member of the South Asian diaspora. She kindly put her installation preparation on pause and sat down with me in the residency room, the morning after staying up until 3:00am slicing vinyl. Below is the interview in its entirety.

Why are you an artist? Is that an obvious question to you, or what else would you have wanted to do?

That’s something I should probably think about more often. What I always wanted to be was a teacher. And I wanted to be a teacher because of my family — I come from a family of teachers who inculcated in my head that education is the key to the world being a good place. And because of that I always really, really responded to good teachers that I had growing up, and was always really consciously aware of the impact they were having on me as a human and as a thinker. I’m not sure when the realization happened, but I think it might have been after I was already teaching — realizing that the coolest thing about being a teacher is that you’re always learning, and that you’re always challenged to think about things in new ways because you always have a different group of people with you in the classroom. So that was an awesome realization: that teaching means that you’re always learning. And everything I’m saying about teaching is how I think about art-making. With art-making it’s never about knowing some concrete thing or reaching an answer or conclusion. It’s about figuring out what you don’t know yet and what you need to figure out next and it’s always about this pushing forward. So to me art is learning — they’re the same in the way that my brain works.

If the walls of your installation could talk, what would they say?

I’ve done a couple window projects — I realized this week that this is another window project, which is cool. My thesis piece for grad school was in a window, so I’ve actually been thinking about this for a while I guess. I think about windows being really different from galleries because windows face outside and they face the public and they’re a space that people are walking by and potentially aren’t expecting to see art. And they might sort of glimpse it and have a moment and say, “Woah, what’s that?” I’m really interested in narratives that are inward-facing, or internal narratives between a community or between a society versus outward-facing narratives that are told to people who aren’t in the inner-crowd, you know what I mean? And I think that window spaces provide that opportunity to speak to people that aren’t necessarily “in the know” or in the organization. And I think for arts spaces that’s really cool — that’s a really important and interesting aspect. Because I think art can be really insular, like a little bubble, and it’s hard for us to think about that and confront the fact that a lot of people aren’t going to walk into your gallery and take that leap to see what’s inside on the walls, whereas with this window space they will. So this work is based on some ideas that I’ve been trying to fit together about garlands and rituals — and, um [laughs]. Sorry, I’m really inarticulate about this because it’s so new. So I’m thinking about how the act of garlanding someone — of putting a garland on someone — signifies various things. So, for example, in a Hindu wedding, it’s part of this exchange ritual that’s similar to exchanging rings in a Christian or Western wedding — which, actually, now Hindus do that, too. There’s this relationship to your body, this relationship to ideas of choice that I think are in the garland. But then I thought about how they’re also used in India as this sort of symbol again of choice and devotion and approval and celebration in politics. And that’s what led me to getting really into this — again, it’s an outward facing narrative. It’s this thing that people do to signify to the audience that this is good — I give my blessing to this politician over all the other ones. And it’s like a performance — its value is in what it represents, not in what it is. And that led me to my title which is Garlanding and Guise, because I want to think about that sort of pretend aspect to it — that performance of approval, that performance of choice — rather than than actual belief. There’s all these interesting things you do in a Hindu wedding that I never thought about — and they’re all very bodily, which is really cool, unlike my experience of Christian weddings where you kind of just stand there and people talk. Like, you have to walk in a circle around a fire; the funniest one is taking each other’s feet and there are these little stones on the ground and you take your partner’s feet and you take their big toe and you touch their toe to each rock. It’s really physical and really interesting. I was studying it at the same time. Partly because my family chose not a priest to do the ceremony but they chose a religious scholar to do it so he kept teaching us about what we were doing as we were doing it.

What is the role of an artist in society today, and how do you fit into that role?

I have a cynical answer to this and then I have the hopeful, optimistic one. I mean, I have days where I just don’t think art has any purpose. I think there’s a slippery slope. You asked specifically about an “artist’s place” and not “art’s place” in the question, and I think that the artist’s place has to be an individual decision. I think we get into tricky territory when we ask ourselves general questions about what an artist should or can do in the world. I would say it’s a great question that every artist should have an answer to, and there should be lots of contradictions and disagreements on that question. I think that, in a way, artists are pretty selfish and we spend a lot of time thinking “What I do as an individual in the world blah blah blah—” but I think that’s actually an important thing that maybe lots of people could spend more time doing, is thinking about who they are and why they do what they do and that is what I think I do as an artist. My favorite way of thinking about this is that artists create opportunities for wondering and speculating that we don’t get very often in our lives. I think that’s true: that a lot of people don’t have time daily to be like, “What if this was something?” or “What would happen if this happened?” So sort of dreaming and imagining and questioning and trying to turn things on their heads and look at it from different angles. So I think that’s what artists do for the world: create opportunities for wild, weird speculations. And posing weirding questions and weird problems to the world. And I don’t think artists provide solutions or answers. I think we provide questions and problems.

In this time of late capitalism when there’s already so much stuff in the world, why make more of it?

That’s a great question — I don’t know really [laughs]. I mean I think this is the point where I think about art and art-making as kind of a religion, because it’s something I think I have to believe in. It’s not about an objective truth. I have to believe that it’s important. Like my answer to your previous question, I believe those things are important, so it’s worth using resources to make it happen, and resources meaning time, meaning material, meaning even things like — you know, I teach screen printing classes and I always remind my students, “We’re using a ton of water. Every time we pull a print and then go wash our screen off, we’re using so much water up. Do you think that’s OK or do you think that’s not OK? Each one of us just wasting water, but we have to think it’s not a waste. And If we do think it’s a waste then we shouldn’t be doing it, right?” But I think that your question — this is actually a subject that I’ve referred to in my work. I did a piece where I referenced the bolt of fabric as a symbol of plentitude, and I think about that a lot in my work. Based on the history of textiles as currency — it used to be like money. And the quantification of textiles is really interesting to me, and it’s something I try to suggest in the work — that very question. Like, thinking about how much material this is and why it appears this way, and how we can sort of reconfigure materials to help us think about values and the value of resources.

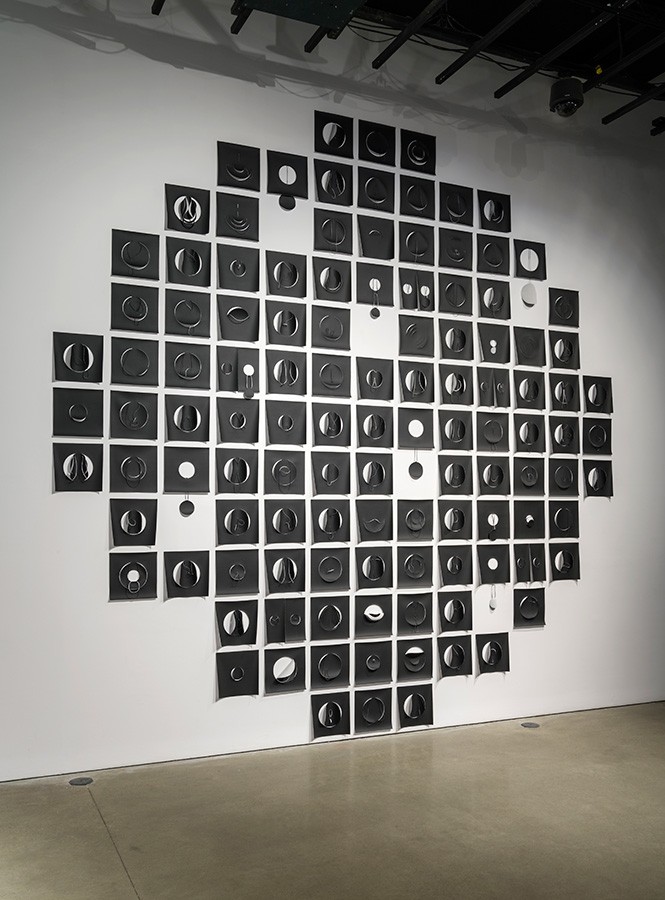

You can definitely see that in the weight of the vinyl in Garlanding and Guise.

I’ve been thinking about this question more and more — I’ve been using upholstery vinyl in my work for a few years, and it’s terrible material. I’m using plastic which means I’m using oil and it’s definitely something that I think is part of the work, and it’s more and more intentionally part of the work to think about that question. But as a material-based artist, these are questions that we all should definitely be asking ourselves and be grappling with all the time.

When did you start working with vinyl?

I first started working with it intentionally a few years ago when I was doing a lot of research into decorative patterning, and I was asking a lot of questions about value and value systems. In the “fine arts” world, the decorative is not valuable — it’s the lowest, it’s not art. And I was interested in challenging that because that’s really — it comes out of Western modernism and tied to that is a lot of really problematic ideas about high and low culture, and that relates to other problematic conversations around culture. Vinyl is a very, very functional material. It exists to be very sturdy, it exists to be waterproof, and it exists to last a really long time. It was developed as a synthetic leather so it was meant for all those things that we used to use leather for. But then it became really fashionable at a time when plastic became really trendy and really popular. I was slicing through it and just by doing that I was rendering it nonfunctional — I was taking away it’s function. The one thing you don’t want to do to a sturdy, waterproof material is cut it. So I was taking away its use-value but then making it into an art object which we might think about as sort of fitting into a different value system. So anyway, that’s a little bit about the train of thought about why I started using it originally.

There’s one last thing I want to know. What’s the last piece of art that really moved you?

Woah … I love that this is the one that stumps me [Laughs]. It’s so funny, I keep coming back to this kind of silly fantasy series I’ve been listening to, but it’s not moving me, it’s just keeping me cutting vinyl. And then I keep thinking of Felix Gonzalez-Torres. I don’t know if I saw a piece of his this summer, but I just think about him all the time. I think the best piece of art ever made is his piece called Untitled (Perfect Lovers). It’s the piece that’s two totally boring, officey-looking clocks. The piece is just a pair of these clocks hung next to each other and they’re battery operated, mechanical clocks. So when you “install” the work, you put the clocks up and set them to the same time and leave it, and eventually they will fall out of sync. That’s it — that’s the whole piece. Felix is one of those artists who figured everything out. Why do I even do what I do if someone already figured it all out? He’s also the perfect artist for people who have trouble thinking about, “What does it mean for art to be conceptual?” If you just described this clock piece, you get it.