Thalassa Raasch (they/she) is a French American artist, educator, and beekeeper based in New England. Photographs ground her work and are often accompanied by audio, projections, or other materials. Thalassa is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor at Maine College of Art and an Instructor at the Rhode Island School of Design.

How has COVID interrupted the Monson Telephone Co. project?

When COVID hit, Dan Bouthot and I were supposed to start producing the stories for the Monson Telephone Co. At first, we paused to see what was going on and if it would be responsible for me to travel to Monson. They had fewer cases and it seemed like a very different feel up there. But we were still exercising caution with me coming from Portland and potentially exposing the town. And then of course our original vision for Monson Telephone Co. was to install a physical phone booth that folks would interact with and take turns putting a receiver to their face, so we pretty quickly realized that while that’s something we still love the idea of and we hope one day that will be possible, given what’s going on, for safety reasons we really had to reassess and say “Ok, that’s not a good idea right now. How can we pivot? How else can this project exist?” We had also planned a lot of public gatherings, a live storytelling event, a walking tour of Monson – these were the community-building aspects of the project. Bringing people together and really collaborating with different townspeople and artists and other folks passing through became unrealistic. The third impact was the issue on my end as the lead artist – that I have just been trying to figure out how to survive. I left a job, and then worked for myself for a little bit and now I’m back to part-time. I have drifted through a lot of employment throughout this time and I personally have been pretty focused on paying my rent, and I finally feel like I’m in a place of semi-stability, feeling like I have a little more time to devote to this.

Have the events of 2020, ( be they COVID, social, political, or otherwise) made you rethink the original concept of the project?

Nothing specifically about what’s going on has greatly altered the project, but it has certainly underscored the importance of initial questions we had about accessibility and representation.

When we first envisioned this project, we were already sketching out a range of stories connected to Monson – both historical and forward-looking, as well as those with brief connections from people passing through as Appalachian Trail through-hikers or as artists participating in the Monson Arts Program. But, the project was always meant to be adaptive and responsive, incorporating new stories as we encountered them. In early 2020, when I read the Kindling Fund press release and saw the other projects included, I reached out to Asata Radcliffe with the Black Guards project which has a connection to Monson. That’s a newer story that we’re working on developing to be included as part of Monson Telephone Co.

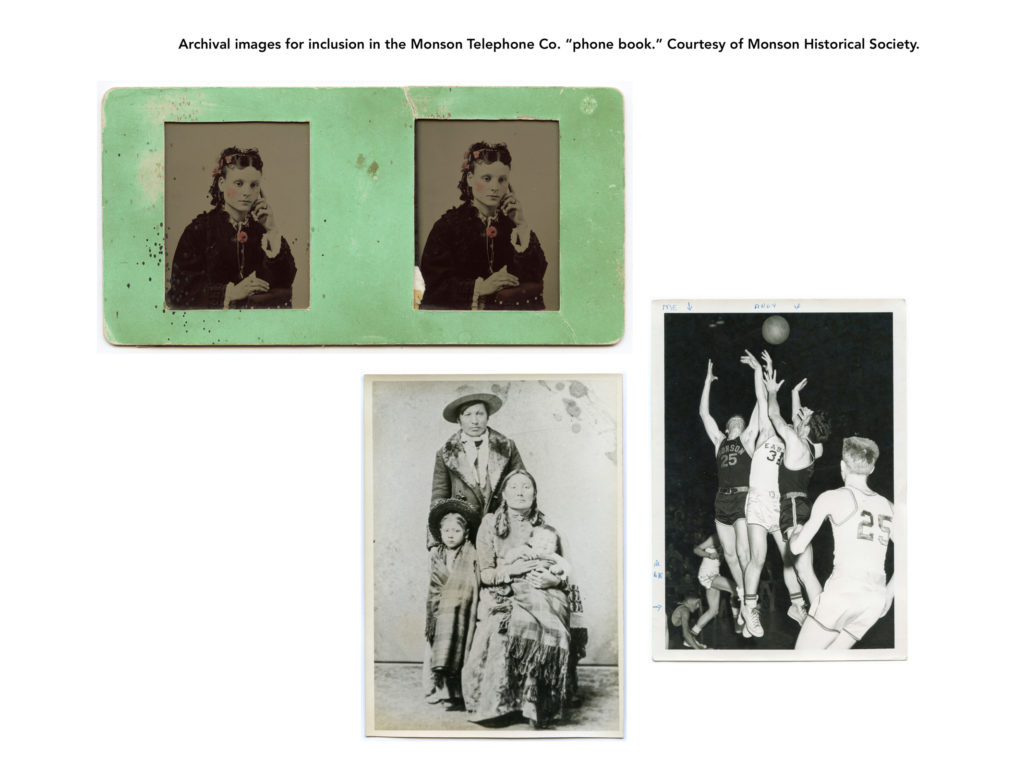

Since the start, we’ve been working with an open question: what are the stories that aren’t represented, or that exist in this place but aren’t reflected in the archives? We are specifically working to find stories from this region from an Indigenous perspective. This is a challenge due to the nature of archiving, whether those stories were listened to, or if they exist from a first-person perspective rather than a white/colonial perspective. That’s something we’re still working on finding, and would welcome any leads anyone might have on this front.

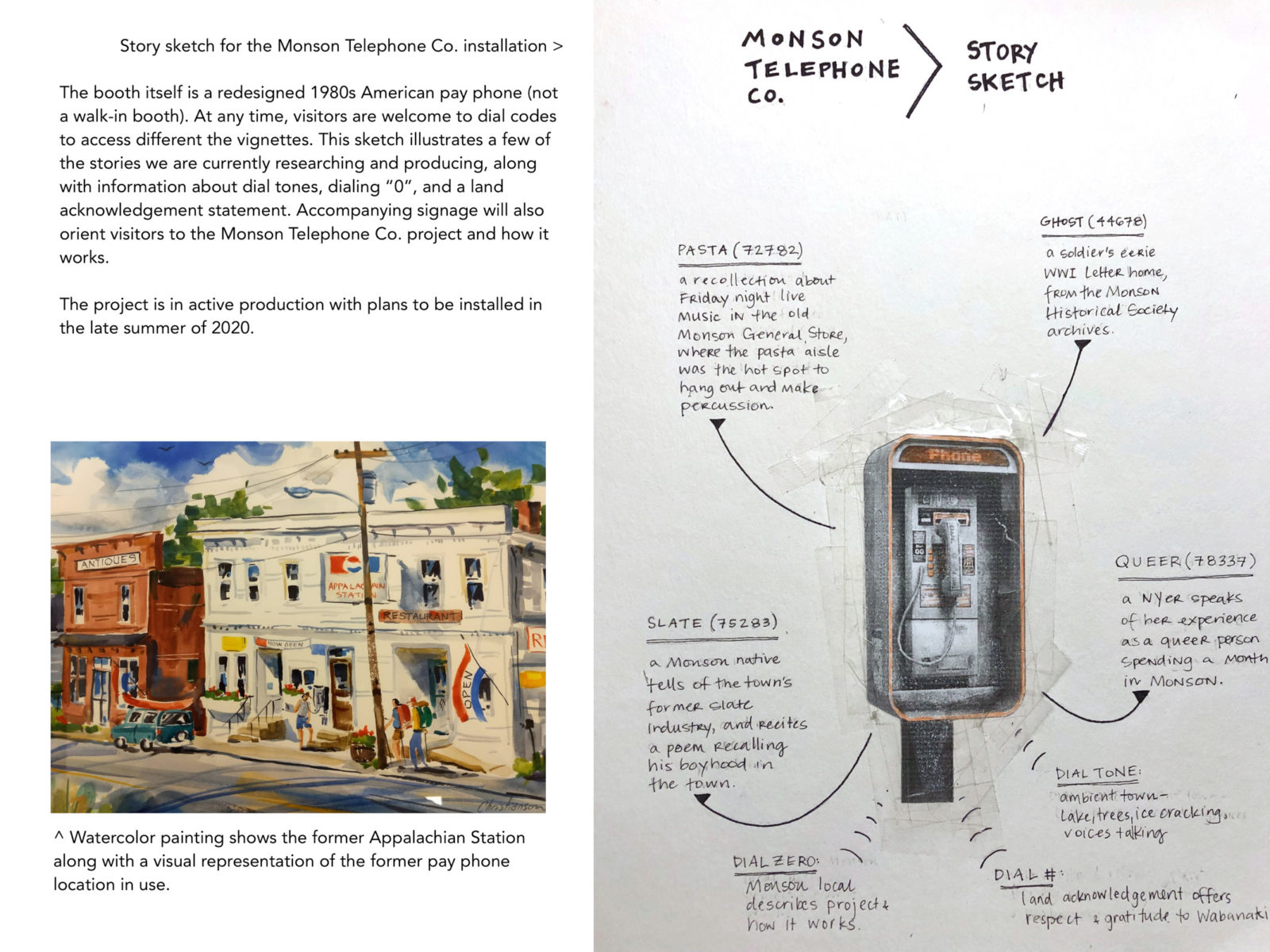

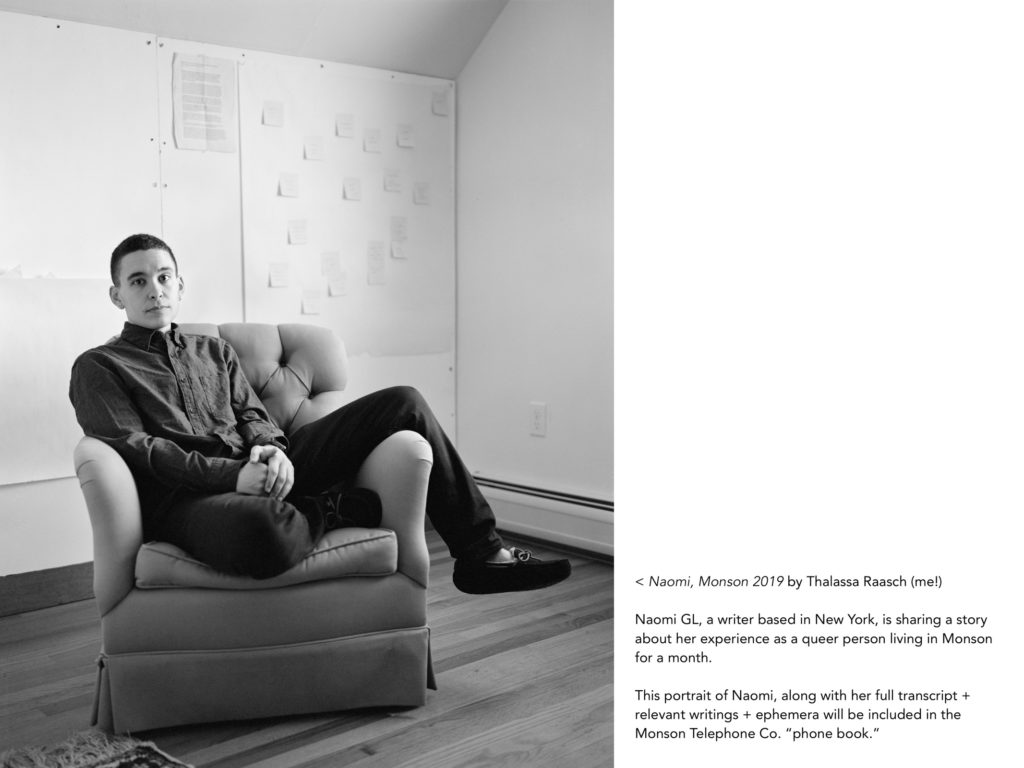

In the original proposal, we had the idea of creating a zine that would have supplemented or been a takeaway item for people to jog their memory about the stories that would have been programmed in the physical phone booth. One way that we have decided to pivot this project is to put more focus towards producing a “phonebook” that would include more imagery, mementos, and full transcripts of interviews and stories that we produce. Now the plan is to include visual materials that wouldn’t necessarily have come across in the audio stories which is really exciting.

We had originally planned to engage the local Monson community first before opening the project to a wider audience. Now, my hope is that the Monson Telephone Co. is still really first and foremost for the residents of Monson, even as it will be able to engage a wider audience more quickly than we had originally planned. Part of this is due to the fact that the audio stories that we still intend to produce will live on a virtual line that people can call into from anywhere in the world.

Why did you choose Monson, Maine for this project?

To some extent it’s circumstantial: I did a residency at Monson Arts and I had never been to that area of the state before. One of my fellow residents organized a walking tour of Monson guided by people who participated in the tour. There were locals who joined and shared these great, quirky stories of their memories of the general store, or a chewing gum factory that used to exist in the town, or their childhood escapades of trying to swim under the bridge from the lake to the canal system. There were also newcomers like me, people who were in town for the residency, who shared their own associations. One woman, a writer, read a letter she had found in the town’s archives that felt like a mysterious ghost story. I was really struck by this celebration of everyday moments and personal memories, the types of quotidian events that take on greater importance and space in a small town’s cultural fabric.

I was really moved by that tour and excited by it. I started talking to Dan, and he said, “there used to be a telephone booth on this building here. Someone should install a telephone booth with stories like this,” and I looked at him and said, “let’s do it!” and that’s really where the idea started.

Monson is a small town in the center of Maine that is undergoing great change, like many rural towns that had a thriving industry, or a local employer that was present for a very long time until those businesses left or closed with the pressures of a globalized economy. It’s the story of a lot of small towns in Maine, except that recently Monson has had a huge investment coming in from the Libra Foundation which is supporting Monson Arts, the development of medical facilities in the town, building renovations, and things like that. There was a consensus within the town to allow this investment to happen. It’s a complicated story of, ‘How do you reinvent your town after the industry has left the region?’ and it’s not perfect, but it’s an interesting model, and an unfolding relationship. I wanted to capture the town at this time where there’s a meeting of two distinct perspectives – those of people who have made their life in Monson for a very long time and then those of people who are encountering Monson for the first time.

Local newspapers are all but disappearing, and we are left with these bigger news outlets at the expense of so much rich local reporting and storytelling that used to exist. This is something I’ve been thinking about a lot: the fact that these regions or these places start to get overlooked more and more. Monson Telephone Co. aspires to elevate the kind of hyper-local stories that we wish got more attention. I really believe that there are stories everywhere, and people that are ready to share information and histories, and it’s just a matter of giving a platform for those to exist and be shared with a wider audience.

As you were talking I was reflecting on the Salt Story Archive and the treasures in it. You’re teaching in the Foundations Department at MECA, and previously at Colby College. How does teaching inform your creative practice?

There are so many ways that teaching affects my practice, the way I approach the world, and art making. Living in a place like Maine, often, because of geography, we artists are spread out doing our own things, but teaching keeps me tapped into an artistic community. It sounds corny as hell, but working with young students who are taking risks and asking difficult questions is sincerely inspiring. It keeps me close to the place of making that is vulnerable and difficult and messy and I am deeply thankful for that. For me, it’s like being close to the source.

That’s a great way of putting that. You work with a lot of different mediums, photography, audio, and video, what is your process for determining what medium is right for a project, when is video right, when is just photography the right choice?

I went to grad school for photography, where I felt really forced to define myself within one discipline, but I don’t think that way naturally. I think in hybrid terms and really feel that I’m an artist first and foremost who prefers lens-based mediums, but works intuitively to gauge process and medium based on the idea for a piece or project.

When it comes to Monson Telephone Co., I had been itching to do an audio project. I’ve been thinking about the immersive space of audio and it’s ability to transport, trigger memories, and simulate experience. It is a powerful medium, either as a straightforward reporting tool or as an experimental device to elicit feelings, reactions, or simply place a listener within an audio landscape. Now, Monson Telephone Co. will focus equally on producing a “telephone book” alongside the audio stories, which is a great example of the potential of being open to hybrid forms of making, how it can allow for important evolution as the project unfolds.

I have always thought of my work as existing in iterations depending on how it needs to exist. For example, installing Monson Telephone Co. in a telephone booth on a street has very different considerations than if it was installed in a traditional gallery space or even online. To me, it only feels right to allow the work to adapt to the new spaces that they need to exist within so that the initial intention behind the work is honored.

For the original Monson Telephone Co. proposal, we had plans to tour the telephone booth throughout the state, installing it in everyday spots like the side of a tree in a public park or at the end of a town pier. We had plans to promote its presence, but also loved the idea that anyone could walk up, discover, and interact with it outside of a traditional art or programming space. I wish more art existed in these interactive and surprising ways without the need to define itself in art spaces. What I like about the Kindling Fund is you’re not allowed to be working in traditional art spaces, and that’s a really powerful challenge.

Do you have a critique of the physical and socio-economic accessibility of formal gallery spaces?

I’ve always felt like it’s important to question the traditional ways that we’re meant to display and share artwork, and succeed as artists. While there’s value and importance to having art in established institutions, those spaces are inextricably caught up in the capitalist, patriarchal, white supremacist fabric that pervades our society. As an artist and human person I feel at odds with all of that. But, I still need to survive, still want to share work with an audience, and still have dialogue with my colleagues. The support of places like SPACE Gallery, the Kindling Fund, and more to foster art sharing beyond traditional art programming space, provides an entry point to begin sharing art more equitably and to challenge these systems. That said, this is not resolved and is something that I continue to struggle with and think about in my practice.

What other creative projects are you working on?

The most recent photographs I made were for a collaborative project called A Yellow Rose Project. It is a project inviting over one hundred women photographers to respond to the 100th anniversary of women’s right to vote in 2020. Note that while that allowed some women the right to vote, it took a lot of time for that to actually mean all women in the United States, and that still leaves out incarcerated women, DACA recipients, and there are still many women missing from that narrative. In my photographic response, I thought about the legends/rumors/language/fears that persist in our culture surrounding the idea of women: everything from older fairy tales (i.e. Little Red Riding Hood) up to present day occurrences (i.e. AOC called a ‘fucking bitch’ in Congress by one of her colleagues). These point to the ways that our culture perpetuates problematic semiotics and lexicon in relation to women. It was really exciting to connect this thought process back to images I had made in the past without quite knowing what they were about but were emerging from my own lived experience, and from an intuitive, subconscious place of processing. Now, I recall some of the first artwork I made as a first year high school student (which no longer sees the light of day!) that was already responding directly to the pressures of being a young teenage girl grappling with contradictory cultural messaging about women, and the pain of that. On some level this is something that I’ve been trying to articulate and figure out as an artist for a long time. Now, I’m looking back on my archives, and treating these new images as the start of a fresh sequence.

I’m going to change gears here… we love cats at SPACE, I was creeping on your Instagram and came across a cat photo at the Museum of Hunting and Nature in Paris, a housecat in a little casket with a blanket over it.

I love cats too! That piece you saw on my gram is by an artist named Sophie Calle, she made this little casket out of an old photo equipment box when her cat passed away and took the photograph before burying her companion. Sophie Heartbreak Calle, folks. She is a huge favorite art crush of mine. She’s a French artist, predominantly working in photography and writing, as well as book making and installation. Her projects are absolutely playful and responsive to the everyday world and people around her, though she’s been very successful in traditional art spaces. She does things like follow someone and photograph them through the streets of Venice, or work as a hotel maid in order to photograph what people leave behind in their rooms. In another project of hers, she was dating this man who broke up with her in a letter, so she decided to make art with it; she shared the letter with women working in different sectors (a psychologist, a scriptwriter, a teenager still in school, a dancer) and asked them to translate or interpret it in their own way using their medium of choice. The book and accompanying exhibition includes their portraits, and reinterpretations of the letters – sometimes text-based, sometimes video, or song. No surprise, I guess, that I’m attracted to Calle’s hybrid making, not to mention her participatory and collaborative approach to the art process.

Other artists that I’m currently loving: contemporary artist Nyeema Morgan recently had a solo show at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art called THE STEM. THE FLOWER. THE ROOT. THE SEED. Her work is incredible, and has a lot to do with myth-making in relation to women. Kiki Smith’s “Wolf Girl” is a specific piece I saw in person in January 2020 that I can’t get out of my head. I think a lot about whether the Wolf Girl grew up to be a Wolf Woman. Finally, I keep coming back to sculptor Doris Salcedo whose work I really really love. Those are my fine art deep crushes right now.

Thank you for indulging that question! What have you been reading recently?

I’ve read a lot this year as a coping mechanism. Some recent favorites …Primeval and Other Times by Olga Tokarczuk that felt like surprise research for the Monson Telephone Co.; it’s the tale of a town that is told in a skipping way between the different people who live or pass through the town over a few generations. Heart of A Dog by Mikhail Bulgakov, that is a satire of Bolshevism from the perspective of a stray dog. In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado which is tough but so good.

In terms of other stories I’m consuming, I spend a lot of time listening to podcasts when driving or working as a beekeeper in the summer. My favorites have been the Italian and animal seasons of “This is Love”, and the entirety of “Have You Heard George’s Podcast.”

Any last thoughts?

I hope that I can give another update on Monson Telephone Co. soon. Despite this year’s setbacks, we’re excited to get this project going. If folks reading this would like to reach out regarding Monson, I’m very much open to your thoughts and ideas and, of course, stories. Please be in touch: thalassagraasch@gmail.com. If you’d simply like to follow along on the progress of Monson Telephone Co., find us on Instragram @monsontelephoneco.

This interview was conducted in late 2020, Thalaasa hopes to have updates on Monson Telephone Co. coming soon. All images provided by Thalassa Raasch.