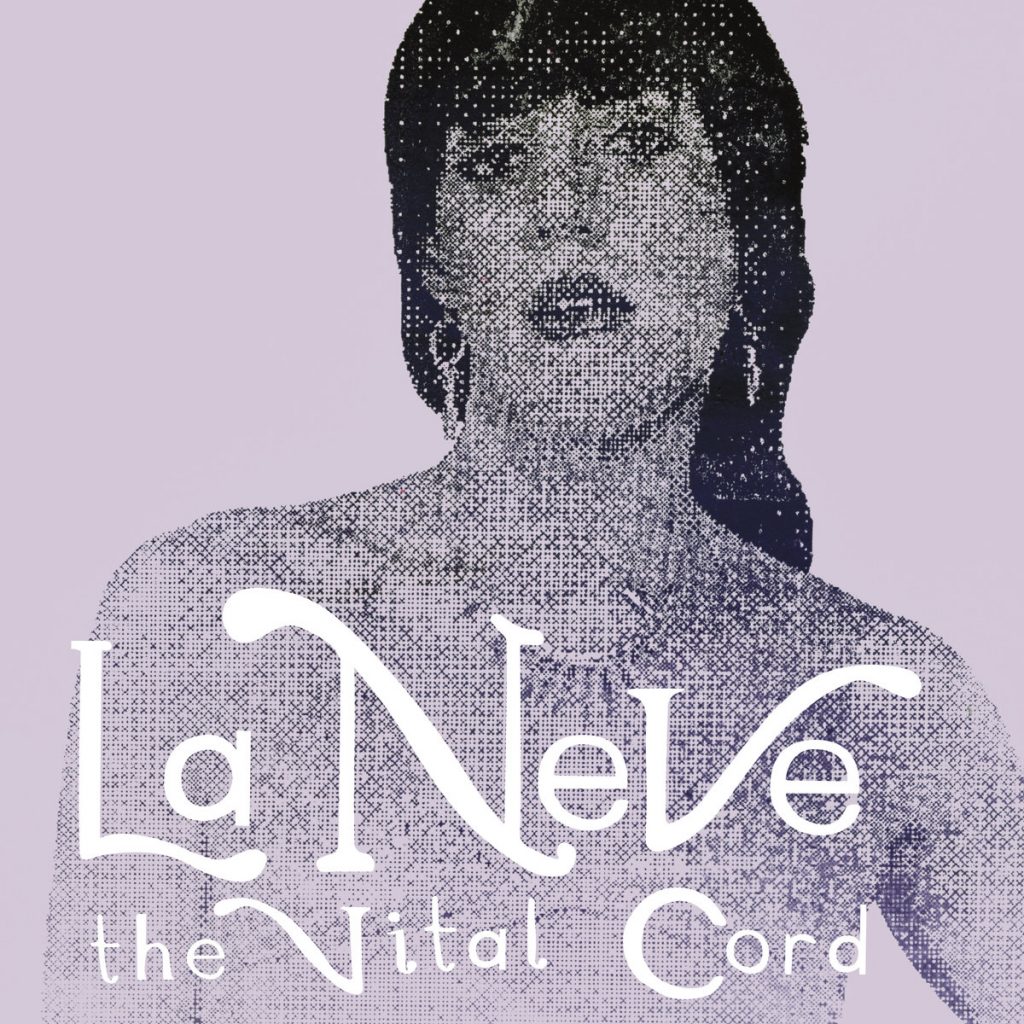

Joey (he/him)/La Neve (she/her)

Joey La Neve Defrancesco is a queer artist performing punk-dance music. Joey is also the founder and guitar player with Downtown Boys and an active labor organizer in the northeast. La Neve put out an EP in 2017 and just released a full LP The Vital Cord this month on Don Giovanni records. Joey’s work intersects history, politics, queer theory, and labor rights.

Are you the person who quit their job with an orchestra to accompany you?

Yes, that was me. I played in the band, the What Cheer? Brigade, for five years.

I’d worked at this hotel for four years and was involved with an intense unionization campaign. Like a lot of service and hotel industry, they treated people, like me, like trash. Once we went forward with our campaign, it got very intense, with things like anti-union backlash from management. They were firing people, and I was one of the loudest people in there, so I had a lot of fights with my management, including the manager in the video. It was finally time for me to leave that job and move on to other parts of my life. In leaving, I didn’t want to give them the satisfaction of getting rid of me, so we did one last big action.

I notice you do a cover of The Stone Roses’ “I Want to Be Adored.” I fucking love this song, why did you pick that song to cover?

I like that record and that band and the lyrics in that song are just so obviously queer to me. I could spin this kind of sexier, dancey song. I know this wasn’t necessarily the bands’ intention while they were writing the song, but every time I listen to it the lyrical and musical content has struck me as a calling for a different kind of treatment. It’s fun to play live because put in this context, me performing it, presenting how I am, I think it really transforms the meaning of the song from this straight, rock band into something different. It’s a fun song for playing with those things.

How would you queer lyrics without changing them?

In the case of that cover, their intention in writing the song was speaking about problems of fame, feeling self-centered, and narcissistic, I imagine, I don’t really know. But when I’m thinking about it, there’s an obvious sexual metaphor that’s pretty heavy-handed, with the lyrics “I don’t have to sell my soul, he’s already in me” and when I’m on stage playing with my gender presentation saying “I wanna be adored”, the bridge of the song over and over again, I think it carries a different meaning about desire and tying desire to how you’re presenting yourself, your gender, and your sexuality to the world. It just becomes a completely different song.

What does it mean to present politics through sexy, queer electronic dance music?

Everything I’ve done has had these political overtones. I’ve been focused on a systematic analysis of things, from the quitting video to stuff with Downtown Boys, which is very explicitly political as well, and with this act, for me at least, it is a means to a personalized liberation, which I think drag is, and performance is for a lot of people. You can express and present yourself how you want to be in the world. The performance allows you to put that out there and become more comfortable with yourself. With this record, there are songs that speak a personal experience, for example, Stability speaks about capital and the barter society creating chaos and precarity and working to destabilize us to keep us disorganized and down… but it also speaks about still striving for personal fulfillment.

What is queer dissidence to you?

I think it can mean a lot of things. On an individual level, having these expressions and being out there and loud with it has been really important for me. My family is really conservative, so doing this project and being public with it, brushes up against a lot of resistance within my family. Pushing back in our personal lives is a big thing. And I think a much more important piece of it is the collective resistance, which right now, of course, is often a matter of life and death. It’s a matter of economic survival, in the case of the Supreme Court that just a couple of weeks ago decided that employers have the right to fire employees based on gender identity, which points very explicitly to the intersections of these things, like a broader labor movement. So queer dissidence is a labor issue and labor issues are queer issues because if we’re in the broader labor movement allowing capital and bosses to target queer people, queer people are workers too. I think if we are going to have an effective queer resistance there needs to be allies and solidarity and thinking very systemically about all these things simultaneously.

How do you think about the intersection of history, gender and politics in your work?

It’s hard to think about how I got there exactly because I think like most things in our lives, you don’t pick it. This is not what I thought 5 years ago, I’m going to combine all these things and go in this direction. It’s just how I’ve gotten there. There is an inherent material reality if you’re a working person, you’re queer, if you’re transgender queer, in this spectrum of things, if you realize your material interests you’re going to be drawn to a certain politics as a general guiding principle. I think it’s all part of the same liberatory project, the union organizer working at this hotel, and also performing and doing drag, and of course, queer people are workers and are in these workplaces, traditionally sometimes ignored by the labor movement. I just got a job at a museum and I was naturally interested in looking at people’s history and working people’s movements and queer history and the history of capital, it’s all intersecting with the same concerns.

Who are your influences? Artists, performers, writers, historians, queers?

I draw on a lot of things. The name of the record, the Vital Cord, is a fitting metaphor for a lot of stuff we’ve been talking about. It was taken from a history book about cotton and it’s referring to the broad historical connections between capital, so how the enormous capital accumulated in the slave trade for instance was then invested in the early industrial revolution and those factory owners invested in banks and many of those banks still exist today in the form of Bank of America or Chase or whomever. Capital today has very deep historical connections to the horrors of the past. The Vital Cord connects us to this horrific past, so when I’m writing lyrics and thinking about things I’m definitely reading history and thinking about this larger systemic analysis.

Musically, I’m coming from the punk world, with the Downtown Boys. I love punk but I have always had a strong affinity for dance music. Dance music has had an important political core to it since it’s inception, although that’s been largely removed by EDM and Diplo world dance music — but house music and techno were all started by queer people of color and often had an explicitly political lens it was speaking through. I think punk is remembered as being political music, but of course, disco from the same era was the true, more multi-racial musical, working-class environment. I think these legacies are really important to recognize, which continue to inspire me.

Personally, I know this work can be quite energizing, but also super tiring. What is your relationship with that?

Doing this tour, doing this act, there are so many extra levels to it. Performing by yourself as opposed to with another person, I’m often doing all the driving and there is this very elaborate visual performance that takes a couple of hours of makeup and getting dressed and often you’re playing some kind of punk venue where there isn’t even a mirror in the bathroom. It’s a very exhausting doing this kind of act in a music industry that doesn’t value queer artists and doesn’t value politicized music. So being undervalued, you’re not making a lot of money at it and need to keep moving all the time and doing other jobs. I think literally every person I talk to around my age is also very anxious and exhausted. Capital has made a highly individualized, isolated, anxious, and precarious world.

And of course on top of that, if you’re queer, if you’re engaged with this kind of work, you get stuff put on you that’s not put on other musicians. Like, I’m enjoying having this conversation with you, you understand where I’m coming from, but when you talk to other people, in the scope of the conversations you end up needing to defend your own existence and your own identity via the questions they are asking. Whereas bands that are considered the default, like straight white guys playing guitars, they get asked about their music, just directly and they don’t have to defend their existence. It’s a different expectation and certainly, that also puts more pressure and intention on yourself, both in terms of how you need to perform for the public but also self-doubt, you end up fighting with yourself to feel authentic or real. Lots of levels to it.

What do you do for self care? How do you keep yourself filled up?

I feel like it’s not what it should be, certainly. I found that because of the obsession with production and anxiety that the way I can clear my mind most is if I’m tricking myself into feeling like I’m producing something, so doing stuff that’s disassociated from money-making, like cooking, taking care of plants, doing things that are active but not. I wish I was able to sit and not do anything, and I think a lot of us struggle with that. I definitely need to find some more self-care. I think having more resources would definitely enable that to be more of a reality. That’s how it goes for a lot of us.