Thalassa Raasch knows how to read a room. And she’s been in some pretty wild ones lately.

Once a Portland resident — where she was a SPACE Studio artist — Raasch (they/she) now teaches photography at the University of Iowa. In a state often seen as a political bellwether, their photography work has found an even grander, if weirder, calling. Recently, Raasch has been on assignment as a freelance photographer for the New York Times, capturing the fervid crowds and expressive oddities at large political rallies and conventions for both major parties.

A graduate of Harvard University and the Salt Institute for Documentary Studies, Raasch’s photojournalism bears the mark of a keen and artful storyteller. While the assignments typically call for little more than conventional shots of political candidates addressing their supporters, Raasch’s eye finds unusually evocative moments, gestures, and sentiments within these mass political gatherings. A photoessay she worked on in July, with journalist Esau McCaulley and photographer Damon Winter, was trained on the “religious veneer” for certain policies discussed at the Republican National Convention (see “The Meaning of Prayer at a Political Convention,” New York Times Opinion, July 21, 2024).

With Election Day around the bend, SPACE’s Executive Director, Kelsey Halliday Johnson interviewed Raasch (also a former Kindling Fund grantee) about their process and experience covering rallies in the feverish political climate of 2024.

What was the first camera you picked up and what were you taking pictures of? What drew you to photography?

Like most kids growing up in the ’90s, I picked up a point-and-shoot film camera my parents had and photographed my daily thrills: turtles in a pond, a lighthouse during family vacation, and my tuxedo cat.

As a teenager I enlisted my sister to pose for staged photographs. Throughout those years, my dad acted as the family documentarian with a chunky VHS recorder – this idea of archiving, of a sort of alchemy of the everyday, drew me in. But, I was mostly drawn to art in general. I remember my aunt setting us up with scissors and nice colored paper to recreate Matisses that we had found and cut out of an interior design catalog. I think, in the end, I was drawn to photography and other lens-based practice (i.e. video) due to the teachers I encountered – they modeled a type of community that I wanted to participate in.

More and more people are seeing your journalism and NYT opinion work on a huge platform, can you backtrack and share what you make in the studio and what has your photographic art practice been about? I miss seeing that silver gelatin print of some kind of cave or hole with vines overgrowing it on your studio door upstairs.

Currently in the studio, I’m researching and developing a new experimental choral work based on my own gendered experience growing up in the Midwest and singing in choirs: in response to recent Iowa legislation that limits reproductive rights and strips LGBTQIA rights, Siren will investigate the voice of femme bodies in the contemporary Midwest, and what it means to sound an emergency. The project idea for Siren is to collaborate with intergenerational womxn singers from a range of Iowa-based singing traditions, and to create a final piece that will exist in two iterations: it will exist as an ephemeral and responsive live performance, and it will exist as an immersive multi-channel audio-video installation.

So, right now, this looks like visiting local choir rehearsals, learning more about the etymology of “siren,” exploring the visualization of musical scores, and scouting locations.

What was your first experience like shooting for a newspaper or on assignment?

My first experience making images for the New York Times was a Vivek Ramaswamy event at a virtual golf space in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

My first bigger political event was a Trump rally in Waterloo, Iowa. Before it begins, you are allowed to explore the room and photograph the crowd. But once it starts, you are placed in a “pen” at the back of the room with all the other journalists so movement becomes limited. At a certain point, we are all making the same photograph from the same vantage point over and over. Such limitations can be frustrating but also yield interesting opportunities. I began to purposefully turn my back on the action (Trump at a podium) and look for other moments, detritus, and details. I should note that I’m lucky to work with editors (shout out to Sara Barrett, Jackie Bates, and Eslah Attar) who are open to this and are looking for the evocative within these frenetic gatherings.

How do these two different kinds of images, a kind of newsy street photography at major events and your studio practice inform one another? What’s fun to get to do with one that you don’t with the other?

In the studio, I am an overthinker and often get in my own way. What I enjoy about these assignments is practicing an opposite kind of process – there is no time to overthink! I am forced to trust my abilities, my intuition, and know that the process of making photographs will lead to visual discovery and growth. These assignments allow me to recall a very important creative skill set and flex that muscle. I do my best to bring that feeling of trust and momentum back into the studio. In short, I love doing this work and it makes me a better studio artist!

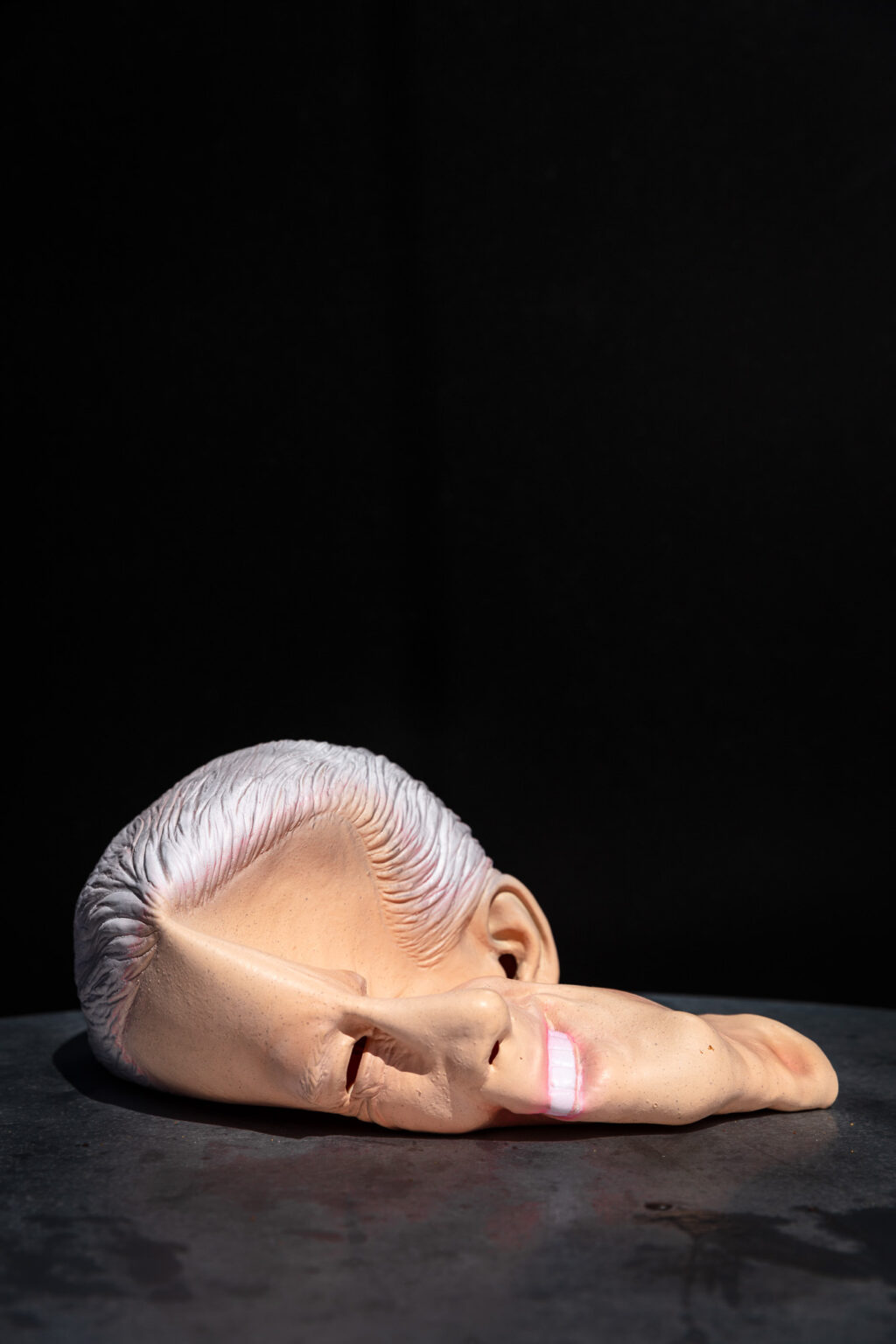

Your coverage of the RNC and DNC audiences have been transfixing on the small details that tell stories about patriotism, zealotry, fan-apparel, and the pomp of these events. What have been your favorite details or stories to tell in these images?

Thank you for the kind words. I think you named them — I’ve been drawn in by moments of prayer, sartorial frills, and fandom. I’m still unpacking so much of what I experienced at the conventions and am working on developing a talk that goes into greater depth and detail about what it means to photograph and bear witness at a political rally in 2024.

I’m sure your friends or students are asking you too, but, what has your experience been like at these two major conventions? How are you received as a photographer/press by people you don’t know?

As someone who has not worked much in journalistic spaces, let alone large-scale political events, my colleagues have been a buoy and boon; the photographers, writers, and more that I have worked alongside this political season have been generous, kind, and bring a good sense of humor to the long intense days. I feel immensely privileged to have overlapped with so many amazing journalists. Photography can be an incredibly solitary profession and there aren’t many events like this where we all come together in the same space. It’s affirming to be surrounded by so many good people grappling with similar visual challenges, ethical questions, and more.

The folks attending the Iowa caucuses, Republican National Convention (RNC), and Democratic National Convention are pretty open to being photographed, and are proud to show off their politics. When possible, I always introduce myself and let people know why I’m making photographs. So, overall I’ve found people to be accepting and welcoming of my presence with a camera. At the RNC, there was an uncomfortable moment where Kari Lake called out the press and encouraged the crowd to locate us — I was by myself in the stands, surrounded by jeering attendees booing in my direction. At that point, I decided to take a break. It’s also worth noting that many of my colleagues were harassed and experienced uncomfortable moments encouraged by the RNC setting.

What photographers are you looking at that inform the various elements of your work? Who are you most excited to teach in the classroom?

This is a great question and I deeply, deeply feel that the artists I look at (and show to students) needs to shift constantly in a way that inspires and challenges. Currently, I’m enamored with Isaac Julien’s treatment of video/video editing in physical space. It’s something that I’m mulling over as I do research and development for a new video installation. I’m building a new lecture on Dionne Lee’s practice and the importance of improvisation as technology, as artistic intelligence — we’ll also be looking at the work of Aspen Mays, Aaron Turner, Odette England, and more in this advanced darkroom class.

Are there any post-project lessons from your Kindling Fund project you’ve carried to Iowa? What was that self-driven project scope like vs being on assignment?

I was fortunate to receive a Kindling Fund for the “Monson Telephone Co.” that was derailed by the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. So, the biggest lesson that I’m still learning to carry is resilience in the face of an unimaginable obstacle. During 2020, my studio practice became much more insular and process-based which was important in a lot of ways but I remain eager to be in conversation beyond my studio walls. I am ever thankful to SPACE for hosting such an incredible grant that celebrates local creative potential with an eye to nontraditional and ephemeral works. One of my favorite times of year is reading about all the recent Kindling Fund grantees and their planned projects.

What do you miss most about Maine?

The ocean! And all the wildly good bakeries.

What do you like most about Iowa?

The prairie! And all the migrating birds that pass through! But also, of course, the lovely arts community that I’m beginning to tap into (shout out to Public Space One which is the SPACE of Iowa City.)

What’s next for you?

Nov. 5th election coverage. Which also happens to be my birthday but I’ll be out in the madness making photos. Please vote!

Cover image: Day 1, Monday August 19, 2024 at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Illinois

Visit Thalassa Raasch’s website for more info. All photos by Thalassa Raasch and shot for the New York Times, used with permission. Edited by Nick Schroeder.