A film can be seen as a failure upon its release, but the finished product never disappears. Time can change our perception, and hindsight and context play a role. Some films only find an audience on home video, years later thanks to puffy vhs cases and curious kids that haven’t developed the dreaded critical eye. What makes a film endure and ultimately be regarded as a good movie may in fact be its ability to age with us, transform with time and also, ultimately exist outside of time. An enduring work of art defines its own parameters. It may not even realize that it exists as a document, as an object, or as a memory.

Disney’s Robin Hood, and Robert Altman’s Popeye are two films SPACE is showing in the coming weeks in Congress Sq. Park (Wednesday Aug 11, and Wednesday Aug 18), and they are two of my favorite films from when I was a little kid. These are family friendly films that for their own separate reasons have complicated histories, but whose odd spirit and energies have embedded themselves in my psyche, and I suspect I’m not the only one who feels this way. These are two unique movies that have nothing to do with each other. Both have source material that their creators depart from in order to create something outside of the constraints of origin. Both films contain some of the best songs ever written for film, and both films are pretty strange in their own crowd-pleasing ways.

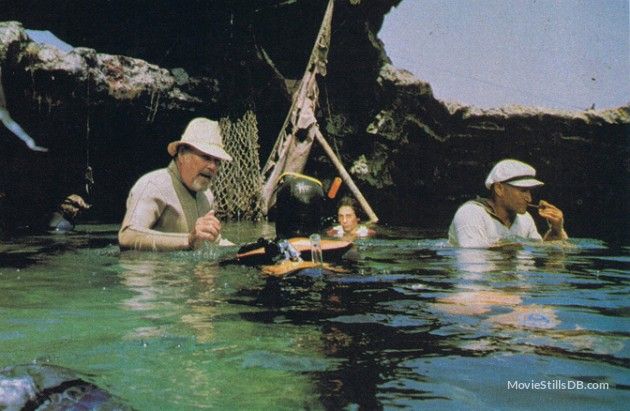

Starting with Popeye on Aug 11- let’s discuss its many nuances. Many articles have been written about its bizarre production and I won’t use this time to delve too greatly into its history but here are some takeaways from me. Robert Altman is such an odd director to take on a musical comedy of Popeye, and that decision could only have been made at the tail end of 70’s Hollywood- a time where uncompromising, auteur directors were given buckets of money and little oversight from studios. Heaven’s Gate is a film by Michael Cimino that also came out in 1980- as Popeye was- and is often credited with putting the final nail in the coffin of director-driven, big budget productions. Popeye sort of fits that bill as well. Rather than finding a seaside New England town to shoot, the isolated Meditarean island of Malta was chosen by Altman- and they essentially built a New England village from scratch just for the film, ultimately needing to import timber from Holland and shingles from Canada to build the elaborate set. It’s also important to note that this is the first film Robin Williams was ever in. A TV star from Mork and Mindy, Williams was untested as a big screen lead, and his performance is as huge as his comically large prosthetic forearms. Shelly Duvall was fresh off the traumatizing production of The Shining when she took on the role of Olive Oyl and her performance contains an intensity and resilience that almost sits outside of the comedy and slapstick implied in its script. All that to say- the film is hinged on these performances, and context and history shows what remarkable life Williams and Duvall brought to the film.

Despite Altman being known as a director of subtle, uncompromising, psychologically complex films- here he is directing a big budget musical intended for family audiences- but wow the songs are good. Written by Harry Nillson and orchestrated with Van Dyke Parks this music is so good- I don’t even know how to talk about it. Rather than just being sung, the tunes seem to escape from the character’s inner psyches. The lyrics are usually simple and direct (“He Needs Me”, “I’m Mean, you know what I mean”, “Everything is food food food”) but with a kind of melodic gentleness and gleeful disregard for conventional pop, or conventional musical-theater. Altman had long perfected mumblecore before it was a thing by highlighting voices not in the foreground, by close mic-ing barely muttered dialogue and sort of handing the script over to a whistling baby (Altman’s newborn grandson as Sweetpea) for large sections of the film, which creates a sort of deluge of voice- it’s not the words, but the way they work together. It’s not the content but the communication and the attempts to communicate that are focused on. This is not a well written film, but it is well emoted and its spirit is intangibly alive 40-plus years later. By the film’s third act a lot of what’s been created has devolved into a sort of chaos. Popeye, it turns out, has spinach related dad-issues that rival any paternal-complex that could be seen in a Wes Anderson film. Suddenly a giant octopus must also be defeated.

When someone asks me what my favorite Disney film is, I always tell them Robin Hood. It’s the one I remember wanting to inhabit as a kid. There was something about the color palette in Sherwood Forest that made me long to step inside, something about Robin and Little John’s deep desire to just chill that felt so immediately important to me as a kid. They know how to relax. Of course that’s not what the film is about, but it sets a kind of desired utopian tone- if everyone could just be cool (and look out for each other), we could all have a good time. The film is more than that, but its rich sense of community, rooting for each other, and helping those that need help always seemed like the pervasive take-away for me.

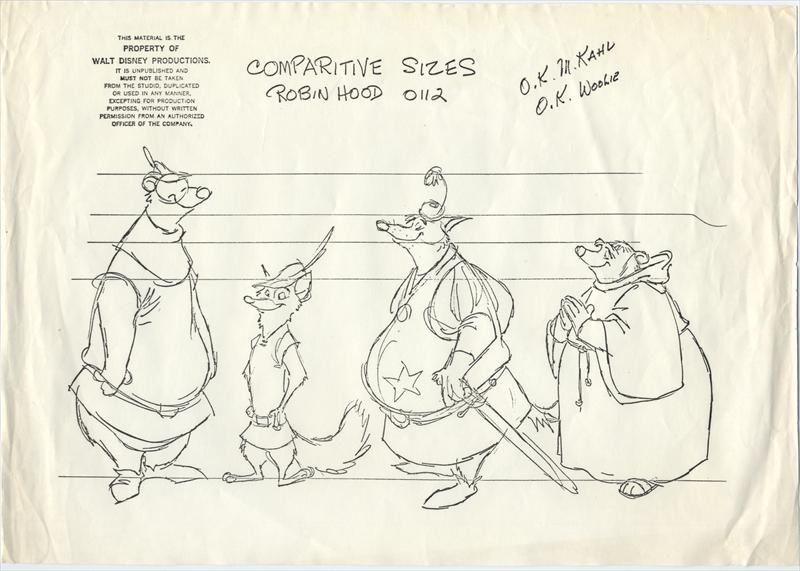

Nostalgia is a heavy lift, and it can be heartbreaking to revisit something that you thought was great and realizing its mediocre. I don’t think that’s what happens when you return to Robin Hood at all, although I was surprised to find that critically the film is considered a sort of less-than in the Disney canon. Completed in 1973- 6 years after Walt Disney died- the film reflects a sort of hodge-podge of ideas that originated from Walt’s ambition to create a Reynard the Fox adaptation in the late 1930’s. A disagreement over where the film was to take place- the deep south or 12th century England- ultimately resulted in a bizarre mix of accents from the film’s eclectic cast. Due to budget and time constraints, several animated sequences were recycled from previous films (recreations, and retracings from Jungle Book, Snow White, and The Aristocats specifically).

There is an overall visual sketchiness to the proceedings, which results in a casual vibe that ultimately works really well with the story and characterizations though. There are some genuinely funny sections and I think above all else, this film is damn cute. The rabbits and turtles are ridiculously adorable, the archery techniques are swoon worthy, and- lets be real- the foxes are foxy. I can think of numerous people throughout my life that have told me that Robin Hood or Maid Marien were their first crushes. Which highlights the fact that this is the first fully anthropomorphic animated film. There are thankfully no humans anywhere to be found, and the animals all walk upright and wear clothes. Psychological ramifications of this are hard to determine, but they make it work, maybe because they never try to make it look too real or too accurate. The music is mostly joyful and heartfelt, but maybe the saddest song in any animated film is “Not in Nottingham”, which contains the animated sequence of all of the jailed, poor and starving animal-citizens of Nottingham. Turtles are spoon feeding an injured dog. One elderly owl wraps another in a blanket, crumbs from a rabbit’s biscuit are shared with a small mouse family. And the -maybe a giant badger?- Fryer Tuck continues ringing the church bell loudly in order to give folks hope. There’s a comradery permeating in the film- a lesson on human rights that can only be told with forest animals. Maybe because humans wouldn’t get it.

Popeye and Robin Hood are films that focus greatly on community, and present very fractured and imperfect worlds. I’m imagining the seagulls yelling at the screen, and let me tell you- this is the right setting for these fractured and imperfect films. These are family films. Bring your pets.