SPACE asked the 12 artists of our spring exhibition, Evening Botanist, how their work relates to the natural world.

Evening Botanist promotes conversation between the works of 12 artists whose practices and projects are grounded in ecological principles, relationships, and/or fantasies. Through their many lenses and media, these artists explore queer ecology, ecofeminism, intersectional environmentalism, and naturalist education, making works in context of the shifting climate and conjuring connection, adaptation, place-making, direct collaboration and fictional inquiry.

Evening Botanist, mixed media exhibition | April 7–May 13, 2023 | Evening Botanist is co-curated by Brian Smith and Kelsey Halliday Johnson. All photos by Carolyn Wachnicki for SPACE.

Rachel Alexandrou

In what ways do you find your local ecology influences the work you are creating?

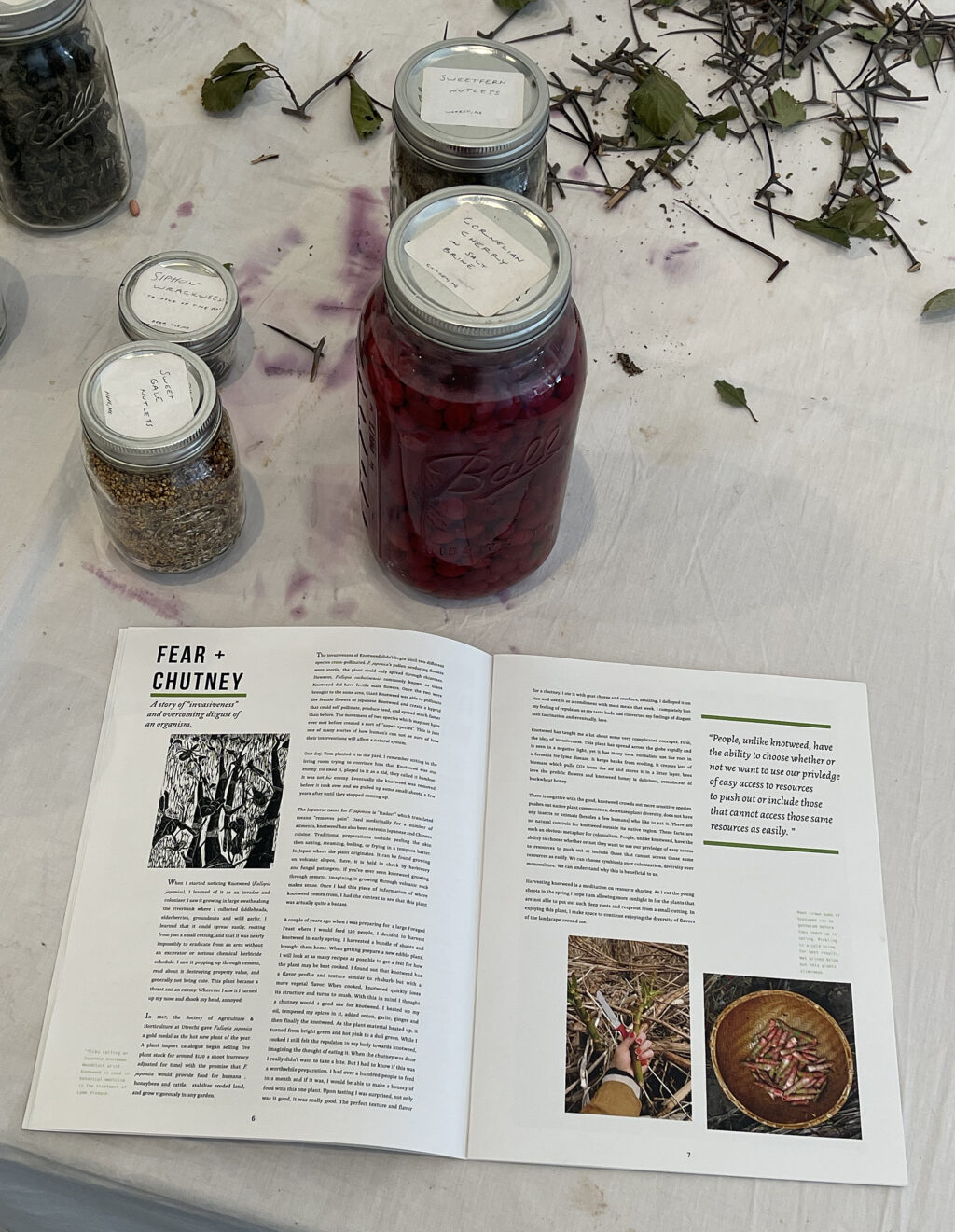

Rachel Alexandrou: I think of my local ecology as food. I want to eat my local ecology, and I do. My local ecology influences the way that I think about recipes. I like to sub-in my local ecology for grocery items. When I go to the grocery store I look longingly at the cattails in the drainage pond outside before I go in. I don’t eat those ones because, runoff, but I look. I also really appreciate the nuanced smells. At the Evening Botanist opening I opened the jars of Myrica gale (aka “Bog Myrtle” or “Sweetgale”) for people to smell the peppery, nutmeg, resinous scent of the tiny nutlets that grow along the edges of many ponds and lakes in Maine.

Is there a specific moment you can pinpoint where you began thinking about your work in the context of the environment?

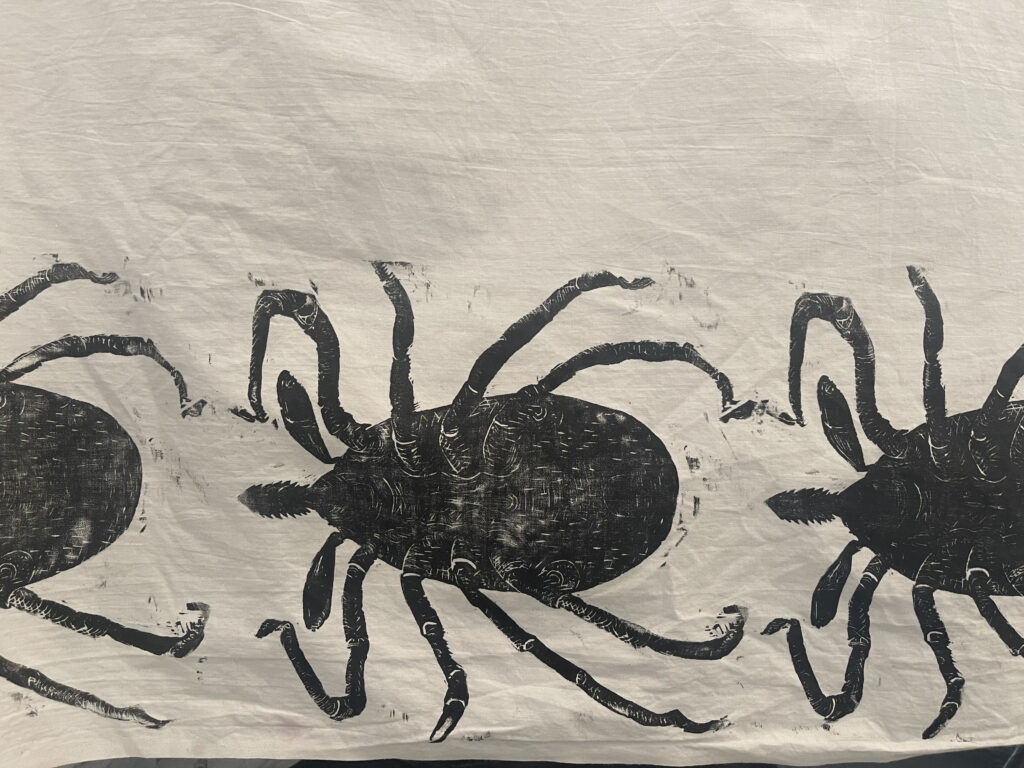

Rachel Alexandrou: I used to want to be a botanical illustrator/science communicator until I realized that I don’t like sitting. My mother said when I was a kid she bought me a chair and I never sat in it. Not the best temperament for an illustrator. In a printmaking class I was taking I began carving ticks and knotweed into birch-ply and making prints that hinted at relationships between the two organisms. I enjoyed the more embodied practice of printmaking. Eventually I began cooking as a way to communicate about plant life. The feasts that I make are propaganda for the plants. Foraging is much more than a harvest. It is a stewardship practice and so by noticing, identifying and cooking with wild plants I can help the plants speak through their flavors, scents, and complex stories.

Is there a specific facet of ecology that fascinates you most?

Rachel Alexandrou: I’ve slowly become more and more obsessed with so-called “invasives” for a variety of reasons. Mainly though, it is the fear that they evoke in us. Knotweed and ticks have been my combo of choice in the past few years but I can feel Multiflora rose creeping into my imagination. I’m interested in the visceral response that occurs when people experience an organism they hate. I.e. the tick or knotweed. In knotweed’s case, I can turn it into a delicious spring chutney and all of the hate dissipates when it’s in my mouth. In the case of the tick, this is more complicated. I can’t avoid the tick with what I do, so I have had to make myself investigate it to mitigate my fear. What are the interesting aspects of this organism? Staying curious when facing fear has been a lesson of learning so much about the ecology of these organisms.

What is a lesson you feel you’ve learned from “nature”?

Rachel Alexandrou: One summer it never stopped raining. That summer all the tomatoes got a blight, the ground was always soggy, saturated, muddy, the mud seeped between my toes when I walked barefoot in the field I lived in. We had a hard time staying dry. It was that summer that I felt the unrelenting, creepy side of the natural world. It’s always stuck with me alongside the romance of nature, there is a wet and squishy underbelly that people tend to avoid, but sometimes it is unavoidable. And then what?

Bri Bowman

In what ways do you find your local ecology influences the work you are creating?

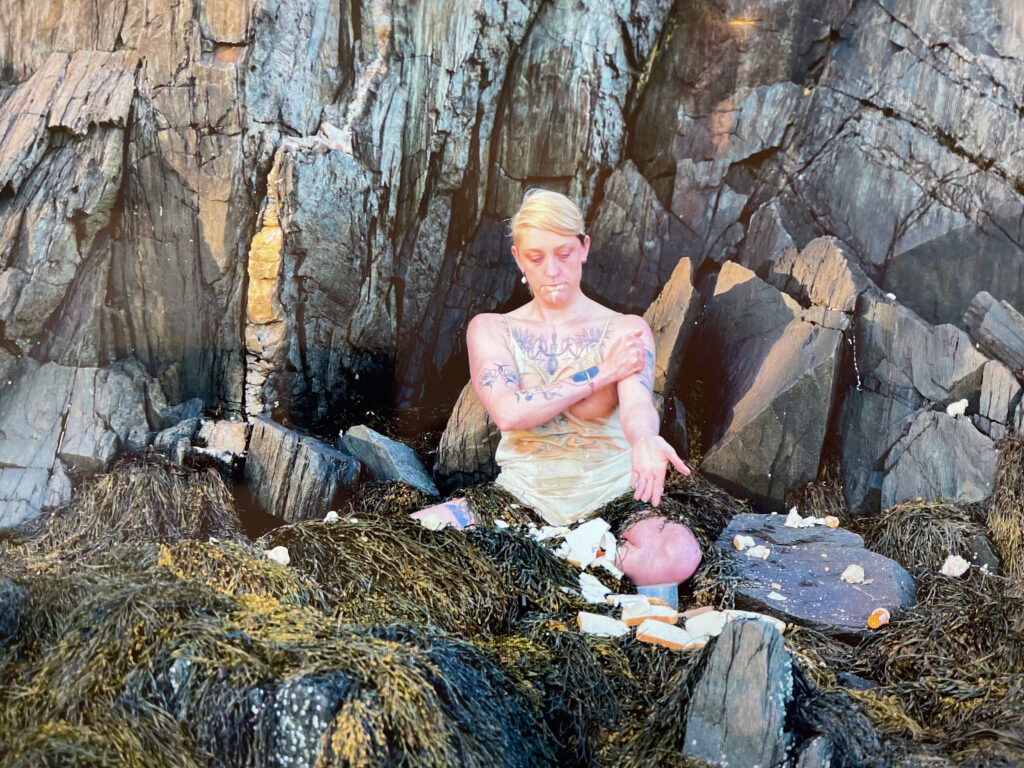

Bri Bowman: The environmental connection of my work is deeply relational and tied to sentimentality, animism, and the way we grieve the loss of both people and places. In considering losses in my own life, I came to view environmental landscapes not only as backdrops but as participants in the experiences of our lives. I believe stone, water, seaweed and grasses are sentient, intelligent, and desirous of relationship. I wonder how spaces that have held us over a lifetime of emotional and sensory experience hold the memory and imprint of both joy and tragedy. I find this duality inspiring and confusing, as there are places that bring me both pain and pleasure, and muddle my perception of time. I wonder how the spaces themselves feel?

What is a lesson you feel you’ve learned from “nature”?

Bri Bowman: The lesson I have learned from nature is that all beings are interwoven in a rich, complex and mysterious tapestry that enables life. This sense of relationship and belonging is a salve for my deepest wounds and an invitation into radical possibilities.

John Brooks

Artist statement:

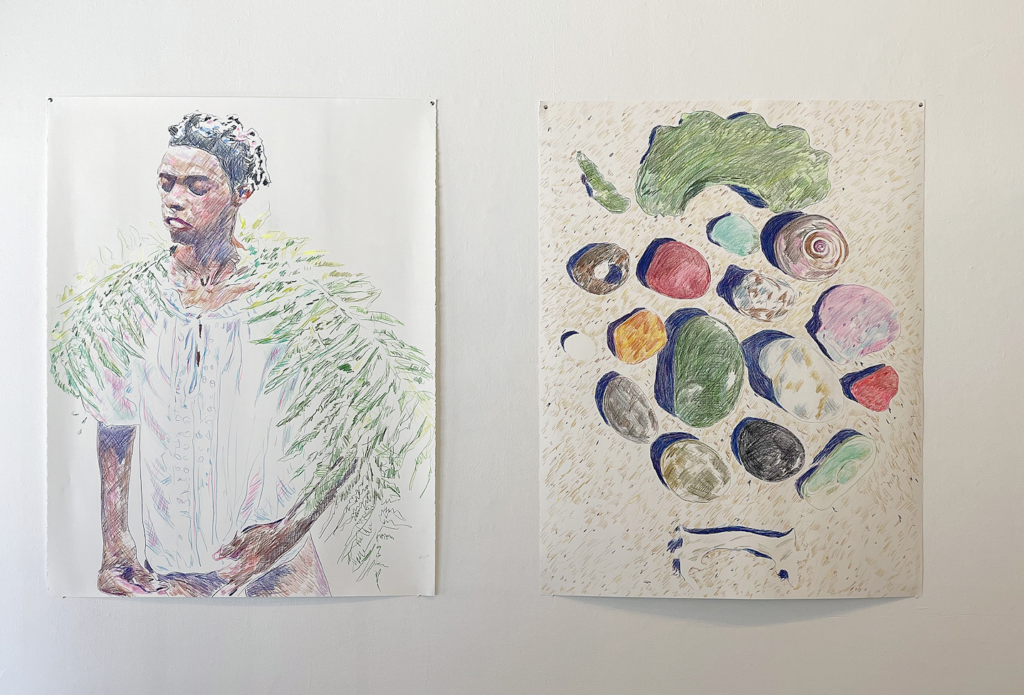

An exploration of Queerness, community, connection, and existence, these drawings are part of an ongoing series of portraits and landscape-inspired works begun in 2021. Their genesis is found in photography—most of the images I take myself, some are found, and others, after being given a simple set of instructions having mostly to do with atmosphere, are provided by subjects. The drawings are a collaboration between my eye, my hand, and what is offered by the sitter or vista. Approached with great reverence, these works distill personal histories, pleasure, loss, and desire within a scale that is joyful, unsettling, and deeply immersive.

Green Ferns Grace is a portrait of fellow artist Elia Grace Green, and a smooth round stone as small as a world and as large as alone depicts a composition of shells and ephemera that I collected and arranged on Halsey Neck Beach in Southampton, New York. The title is taken from e.e. cummings’ 1956 poem maggie and milly and molly and may, which concludes with the line: for whatever we lose (like a you or a me) / it’s always ourselves we find in the sea.”

Oscar Chacon

Is there a specific moment you can pinpoint where you began thinking about your work in the context of the environment?

Oscar Chacon: In 2016, I took an introductory course on nature and environmental writing when I was in undergrad and thoroughly enjoyed it. I was exposed to the writings and poems by nature writers, like Annie Dillard, Toni Morrison, Lucille Clifton, Thylias Moss, Camille T. Dungy, Wendell Berry, Berry Lopez, and Gary Snyder. I enjoyed reading their detailed descriptions of the natural world, while others juxtapose observations about the world with reflections on science or sociology. The course was taught by Romi N. Crawford, and she was so passionate about the texts we were reading, and engaged my curiosity a lot. I still have all of the printed handouts from that class, which informed my own questions around my art practice and relationship with the natural world.

This show brings together a wonderful range of ways to think about “nature” through a queer, feminist, intersectional, and/or naturalist education lens. Are there artists addressing similar topics that you are looking toward?

Oscar Chacon: For me, it’s Black, Brown, and Queer artists making music today who sing about humanity’s detrimental impact on nature. Eco-conscious music has reentered the mainstream in the last few years — with artists like Bjork, ANOHNI, Solange, Hurray for the Riff Raff and Kelela. All making music that takes on the unprecedented climate crisis, and questioning how much longer the planet could sustain human life. Through their music, artists and their listeners can shift their intention on fantasizing an experience without environmental degradation.

Heather Flor Cron

Is there a specific facet of ecology that fascinates you most?

Heather Flor Cron: I am interested in how my Indigenous ancestors lived in relationship with the land and animals around them. How do you continue to live intentionally and consciously when you have been violently pushed off your motherland? How do you continue to live in this intentional and conscious way when the dominant white settler culture does not recognize flora, fauna, and others outside the hegemonic race as kin but as resources to be exploited? I continue knowing generations of knowledge live within me. I need to remind myself and others that this is not new, this is the remembering of ancient wisdom. I believe once Black and Indigenous people are acknowledged as ancestral caretakers of the land, we will begin to see deep healing in ourselves and Pachamama.

This show brings together a wonderful range of ways to think about “nature” through a queer, feminist, intersectional, and/or naturalist education lens. Are there artists addressing similar topics that you are looking toward?

Heather Flor Cron: Mikayla Patton (@makaylapatton.art), Sonja John (@sonja__jay),

Dalila Sanabria (@dalila.sanabria)—these three queer BIPOC women inspire me. They are looking toward the culture, rituals and landscapes of their motherland as a way to explore the relationship between one’s body and environment and excavate identity as women whose ancestry is ravaged by colonialism. I see them answering questions like “how do you make art about a relationship to land as a Displaced person?” They take the pieces of what is left and what has been resilient against centuries of violence. They reference the flora and fauna of where their people have come from or passed through. They create a world where I feel hopeful for the Queer BIPOC that are and will steward the land again.

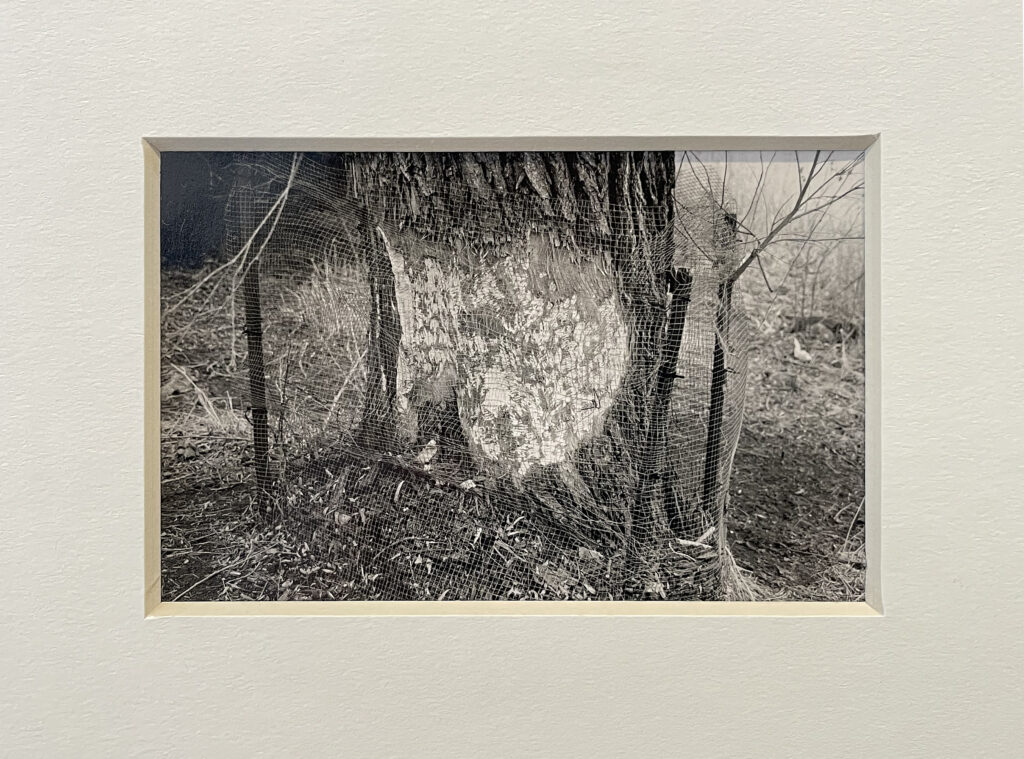

Dylan Hausthor

Right: Dylan Hausthor, a tiny hole probably filled with incredible objects, 2023, 43″ x 53″, archival pigment print

Is there a specific moment you can pinpoint where you began thinking about your work in the context of the environment?

Dylan Hausthor: For me, it feels impossible for the two to escape each other. I’m interested in storytelling and the extraordinary—dying, fucking, thriving, giving birth, love, caution, abandon, absurdity, touching, lying and laughing. The environment is nothing if not full of these things.

Is there a specific facet of ecology that fascinates you most?

Dylan Hausthor: The sun can’t ever see the shadows it casts.

Owen McCarter

In what ways do you find your local ecology influences the work you are creating?

Owen McCarter: For the last three years my work has been centered on the Housatonic River in Western Massachusetts and pollution caused by the General Electric superfund site at the river’s source. Growing up in a place in the process of remediation has profoundly affected the way I engage with landscape and representations of environmental destruction. It has made me question if it is possible to visualize hope within a site of toxicity? Can photography be used to shift the binary that describes the post-industrial landscape as unusable wasteland? Can it instead encourage community engagement with the spaces we inhabit? My environment has given me a voice to articulate the relationship between place and identity in both my personal experience and within a communal and historical context.

What is something you learned in your relationship to the material world through making the work in this show?

Owen McCarter: The pieces in the show are all experiments drawn from different parts of my practice. Things I am not necessarily comfortable with yet. Making the triptych taught me a lot about the frames ability to recontextualize an image in space. It enabled me to combine a moment of male intimacy in nature with the language of religious iconography. Using the arrangement of images to place something typically underrepresented into a historical context and play with friction between queerness and Christianity. It’s something I’m very excited to explore further within the exhibition space.

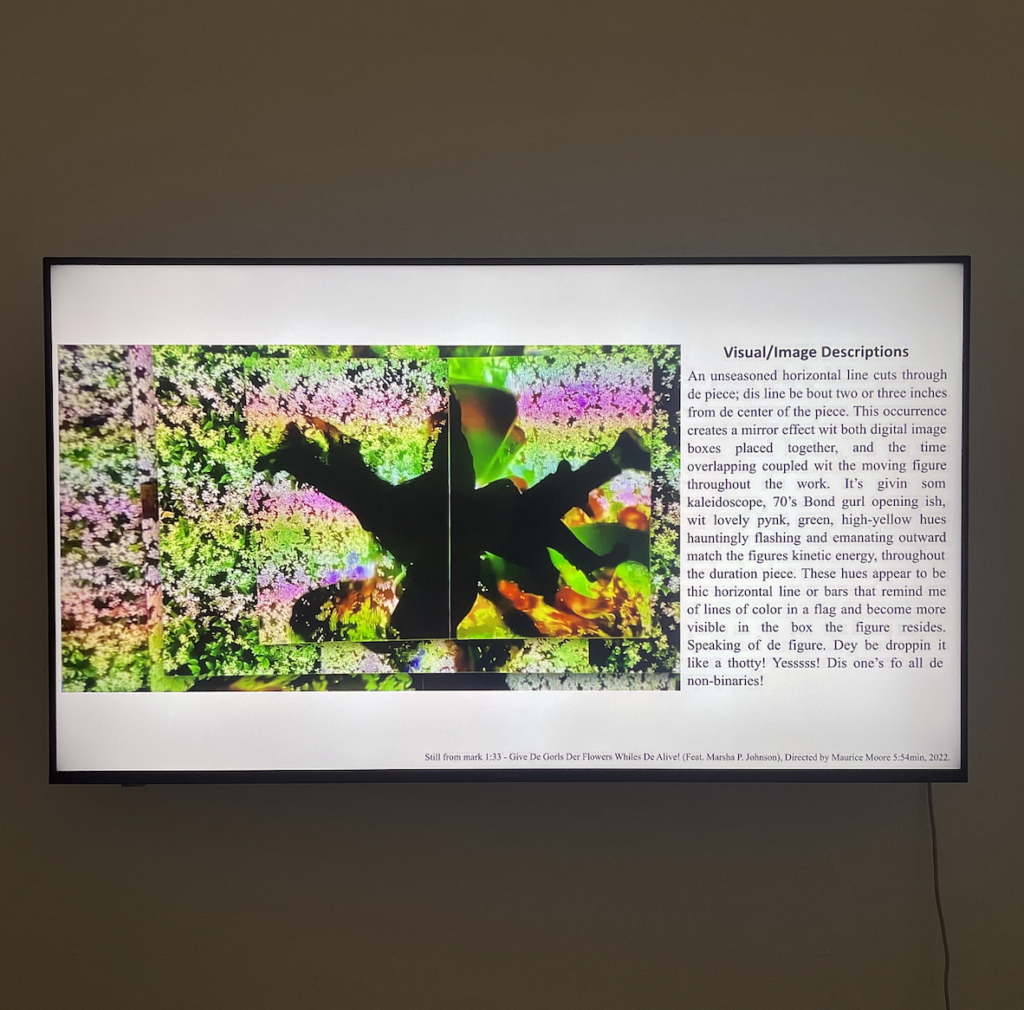

Maurice Moore

Is there a specific moment you can pinpoint where you began thinking about your work in the context of the environment?

Maurice Moore: Being and becoming as a Trans-Nonbinary person on my terms and coming out in various environments has been filled with many moments of both euphoria and dysphoria not only in the creation of Nonbinaries In Nature film Series Marked Bodies Video 1,2,3,4 but also exhibiting the works as well. Navigating sexuality, gender, and race among many other amazing parts that make me up in my queerness journey has been very liberating to say the least. These pieces are complicated and scary in many beautiful thrilling ways. Being able to exhibit these werks with other queer creatives in this environment that SPACE offers is affirming and healing.

What is something you learned in your relationship to the material world through making the work in this show?

Maurice Moore: With dis werq in de material world, I am learning more and more about how much power Queer folks Gestures, Expressions, and Impulses both in Visual and/or Verbal form(s) i.e., “Signifying” carries in the world. Lastly, dees pieces in the exhibition Beez dedicated tuh de ancestors, all de legendary Ball churen both past and present, and our decedents. 3 Snaps!”

Travis Morehead

In what ways do you find your local ecology influences the work you are creating?

Travis Morehead: Everything within my practice is guided by a certain participatory logic, which finds its shape through tending to my immediate surroundings. I take my lead from the innumerable relationships that are always present, and work to bring more conscious attention to the ways in which we all share space together. I think this ultimately stems from a desire to cultivate intimacy and connection across difference.

The work included in Evening Botanist is a result of getting to know a family of beavers that live in a human-made lagoon a short walk from my studio. Obviously this is a pretty novel situation, but beyond the specifics of this particular context, I hope for my work to model a form of engagement that is available to anybody, anywhere, with enough patience and curiosity.

Is there a specific facet of ecology that fascinates you most?

Travis Morehead: Lately I’ve been interested in the physical contours of relationships and their co-mutability through time. An edge is also an interface, and it’s from within the seams that new possibilities for being can emerge.

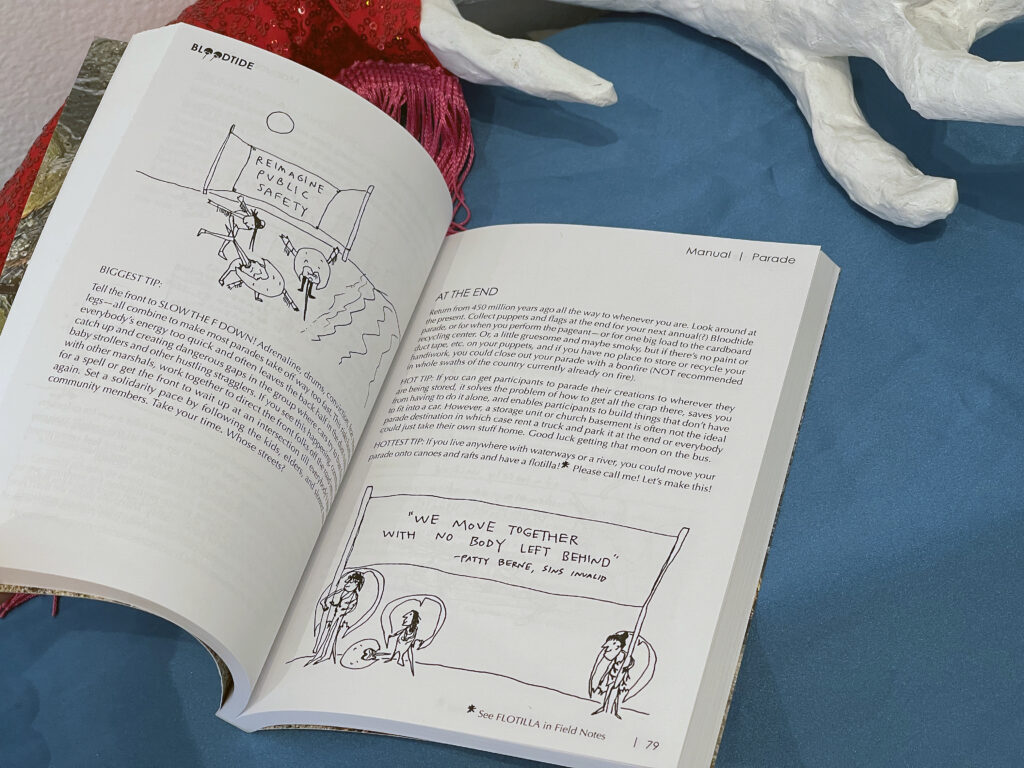

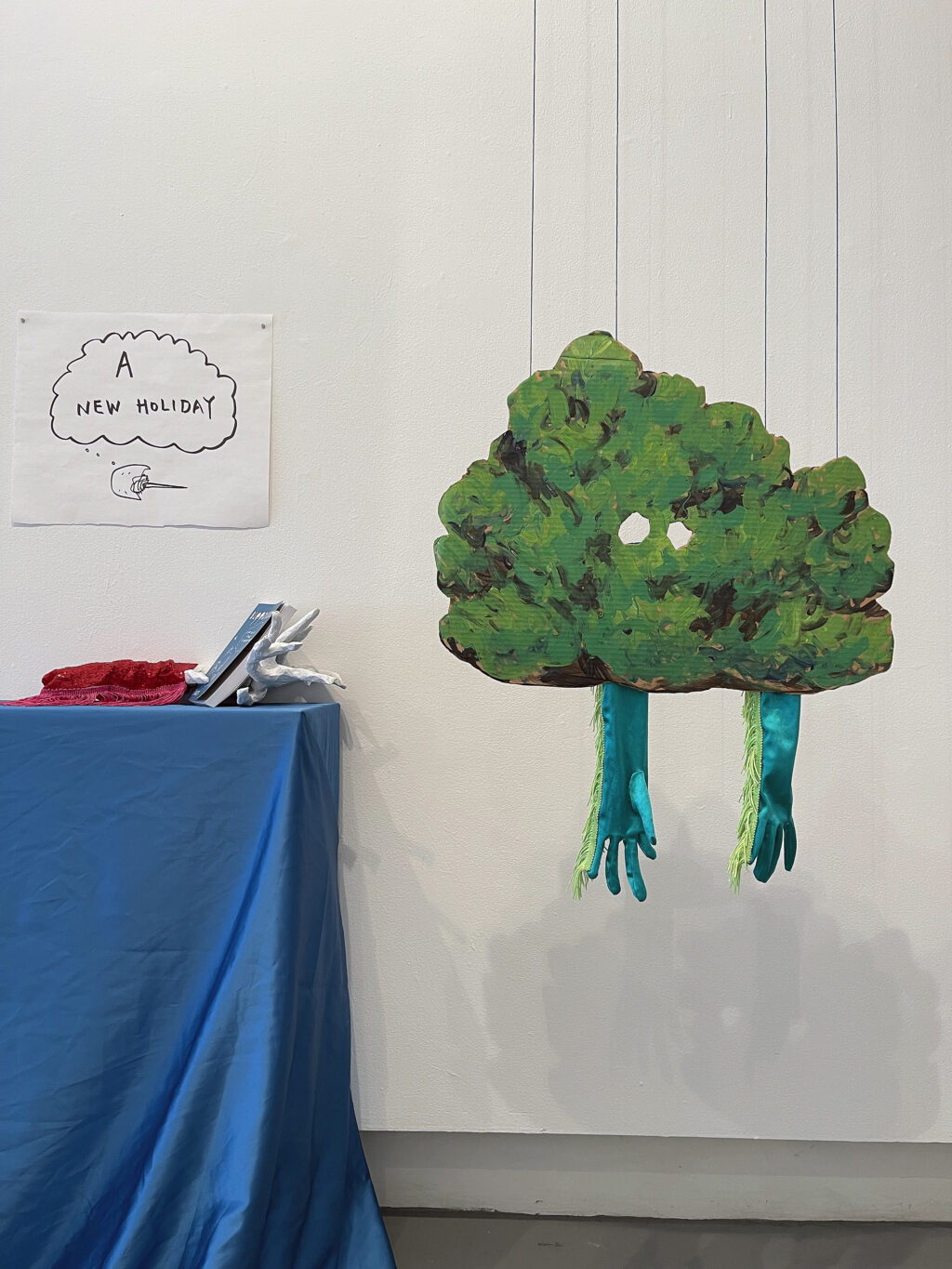

Eli Nixon

workshop drawings

Artist statement:

Eli is in the midst of proposing a new holiday in homage to horseshoe crabs called, “BLOODTIDE”. The book on view is an illustrated manual for activating the holiday, and the related ephemera come from their suitcase theater holiday proposal show and naturedrag workshop that took place at SPACE and Speedwell Projects earlier this month.

Eli describes their gender as ‘platypussian’: mammal/bird/reptile, glow-in-the-dark, egg-laying, and milk-feeding, a critter both unique and combined. Naturedrag is a process of basking in neither king nor queen, but a 3rd solidarity outside and in between–dragkin.

Drawing “exquisite corpses” is helpful in this pursuit. Thanks to participants of the 5/31/23* naturedrag workshop for releasing their body part drawings to the unknown / this exhibit.

*Trans Day of Visibility (maybe a camouflage bush face and gloves?)

Visitors are encouraged to try on naturedrag for themselves and see what evolves…

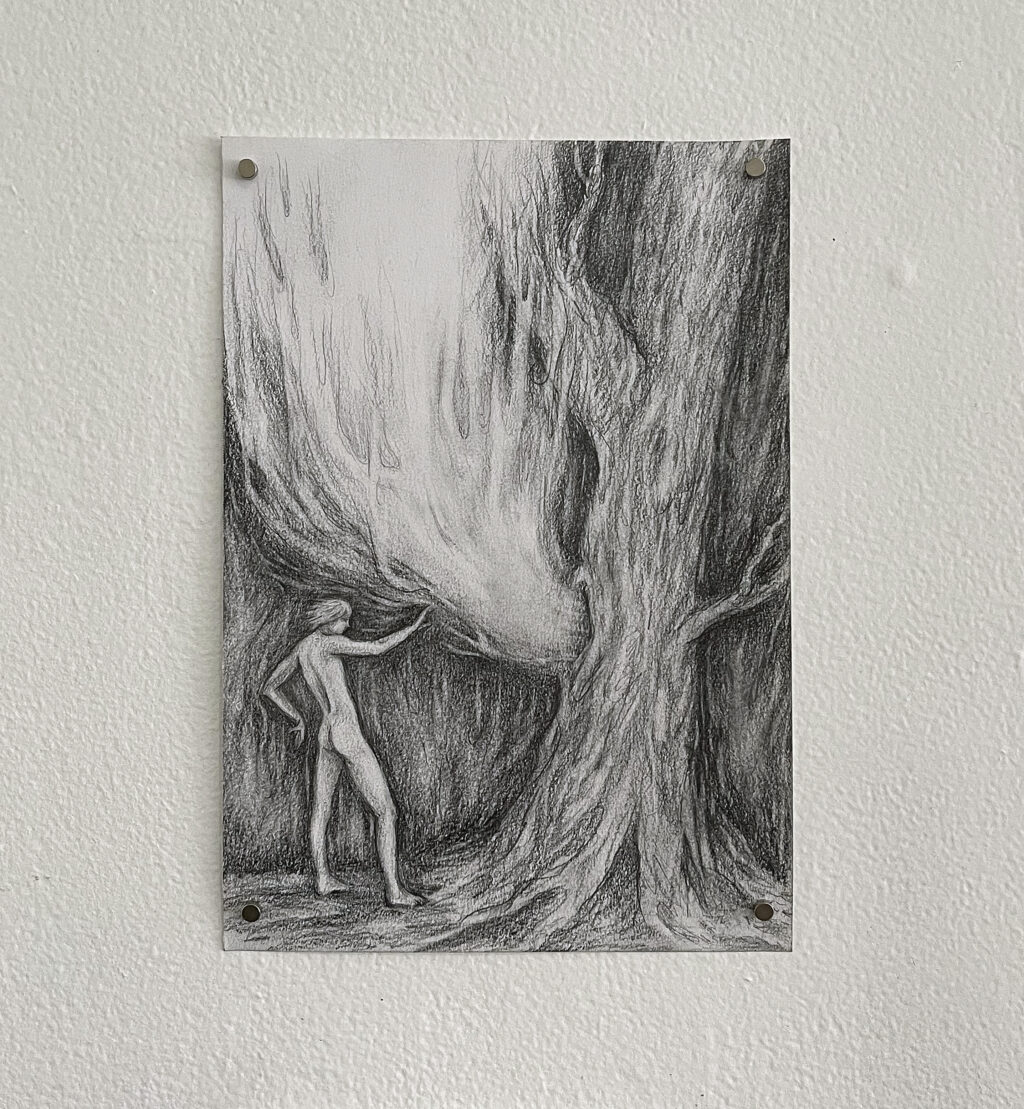

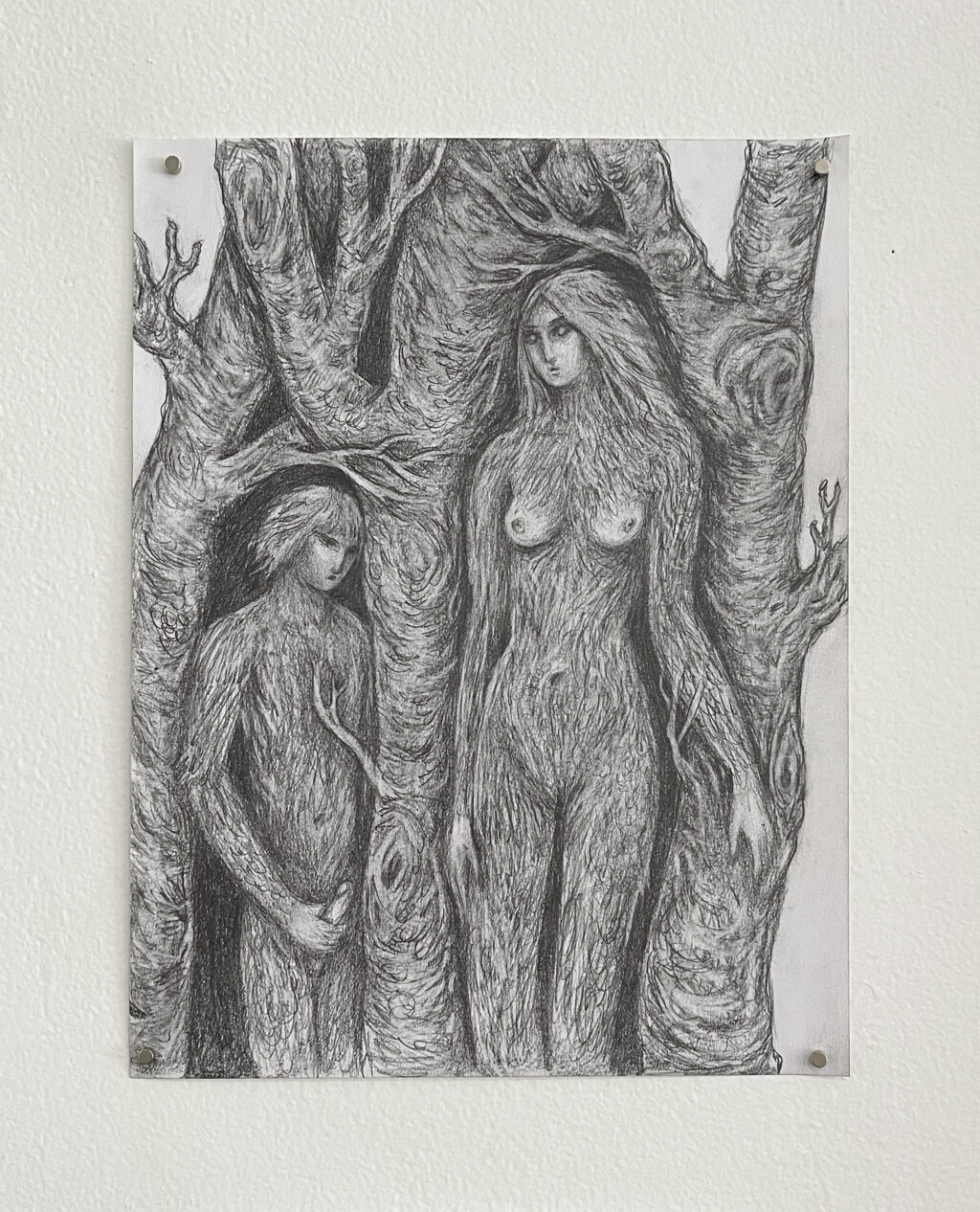

Charles E. Roberts III

In what ways do you find your local ecology influences the work you are creating?

Charles E. Roberts III: I recently began drawing again after nearly twenty years of working in assemblage, video, photography and installation. It was a conscious decision to simplify my practice and lifestyle on the whole. Drawing had been my earliest form of expression and something that I’d done obsessively up until my mid-twenties. I’ve lived in cities for more than half my life now but the return to drawing also marked a return to the forests of memory and the rural childhood in which the woods were my backyard.

Is there a specific moment you can pinpoint where you began thinking about your work in the context of the environment?

Charles E. Roberts III: Growing up, I spent more time with trees than people and the solitary act of drawing has me metaphorically taking refuge amongst them once again. I’ve recently begun to engage more directly with the local flora and fauna here in Chicago and I’m looking forward to a rigorous practice of drawing in its parks and preserves in the coming summer months. There is definitely a pull toward a here and now that is troubled by a future even more precarious than memory and myth.

Brian Smith

Artist statement:

This work explores humans’ relation to the greater environment through a queer lens. The objects I create derive from my interpretation of the natural world, and are inspired by organic elements that, through my work, fall into the category of queer ecology. The facet of queer ecology that I focus on centers humans’ relationship to nature, with a yearning to reconnect and identify with the non-human world. Technology and consumerism have brought humans to a place distant from the natural world, that people hardly see themselves as being of-nature. Further, legislation continuously seeks to claim queerness as an unnatural phenomenon. This work offers moments of self-reflection, desire, and awe to help re-spin the webs tethering queerness to nature in the age of the climate catastrophe.

About the artists

Bri Bowman navigates longing, loss, ecology, and deep time in their multimedia practice; combining performance, sound, and sculpture to explore landscape as an internal experience and external phenomenon.

Brian Smith’s work uses sculptural form, inspired by plants and animals, to highlight the facet of queer eco theory that focuses on humans’ relationship to nature, with a yearning to reconnect and identify with the non-human world.

Charles E. Roberts III uses charcoal, ink, watercolor, colored pencils, and other drafting materials to metaphorically revisit the forests of their rural childhood through the language of folklore.

Dylan Hausthor makes photographs, videos, prints, writing, and books that think about mythmaking, disinformation, storytelling, and ecologies.

Eli Nixon builds portals and gives guided tours to places that don’t yet exist through cardboard constructionism, playwriting, choreography, and bookmaking.

Heather Flor Cron is a queer Peruvian-American farmer, performer & transdisciplinary artist who works with intuitive movement, dirt, installation, printmaking, fiber, and food.

John Brooks‘ work is an exploration of Queerness, community, connection, and existence, through distilled personal histories, pleasure, loss, and desire on a scale that is deeply immersive.

Maurice Moore’s drawing practice in expanded media interface with Black theory to create immersive environments and engaging experiences relating to race and gender identity coupled with black hxstories and cultural diasporic traditions in Amerikkkca.

Oscar Chacon’s collage and draftsman-based practice centers an exploration of identity—particularly his experience as a queer/Latino person— to understand and express himself and connect with the world around him.

Owen McCarter is a documentary and performance based artist living and working in Western Massachusetts, who is exploring, as Emerson wrote, “the suggestion of an occult relation between man and the vegetable.”

Rachel Alexandrou is a plant propagandist who works in the mediums of foraged food, printmaking, watercolor, prints and installation.

Travis Morehead is an interdisciplinary artist thinking about intimacy, ecology and loss through poetics and gift giving.