Somewhere there’s this Tom Waits interview where he says something to the effect of: If you’ve got two guys, and they both can do all the same things and do them equally well, then you’ve got one too many guys. This is kinda how I feel about a lot of traditional musical forms. What more can really be demonstrated within the strictures of the 12-bar blues? Of the verse-chorus-verse pop song? Of the infinite noodle of bluegrass? Don’t we already have enough of these kinds of songs?

Of course, it’s only when the traditional is interpreted and executed dogmatically that these concerns become problematic. Approach the form not as a set of rules but as a reducible or expanding framework—a skeleton to adorn or deconstruct—and what’s limiting suddenly becomes a wide-open door. An opportunity to turn the rules against themselves. To add to the lexicon. To question the motive.

It’s this exact approach that makes Ben Trickey something more than yet another sad white boy with a guitar. With feet planted evenly in the traditions of punk and country—genres that, too often, are draconian in their adherence to format—Ben has found a way of exploring the emotional, mental, and physical geography of unremarkable people (you know, like you and me) without ever resorting to the well-paved routes of songwriting. Sure, heartache sucks and at best is only ever backstage, waiting for its cue. But the same can be said of debt. Or losing your job. Or keeping a job you hate. And just as ubiquitous are the ephemeral joys of an unexpected slow dance, of a little sugar stirred in your coffee, of being thirsty and then being given a drink. All of these things—the hurt and hope alike—are contained in the universe of Ben Trickey’s songs. In the years I’ve known him, this universe is only growing richer, more deeply twilit and terrifyingly close to home.

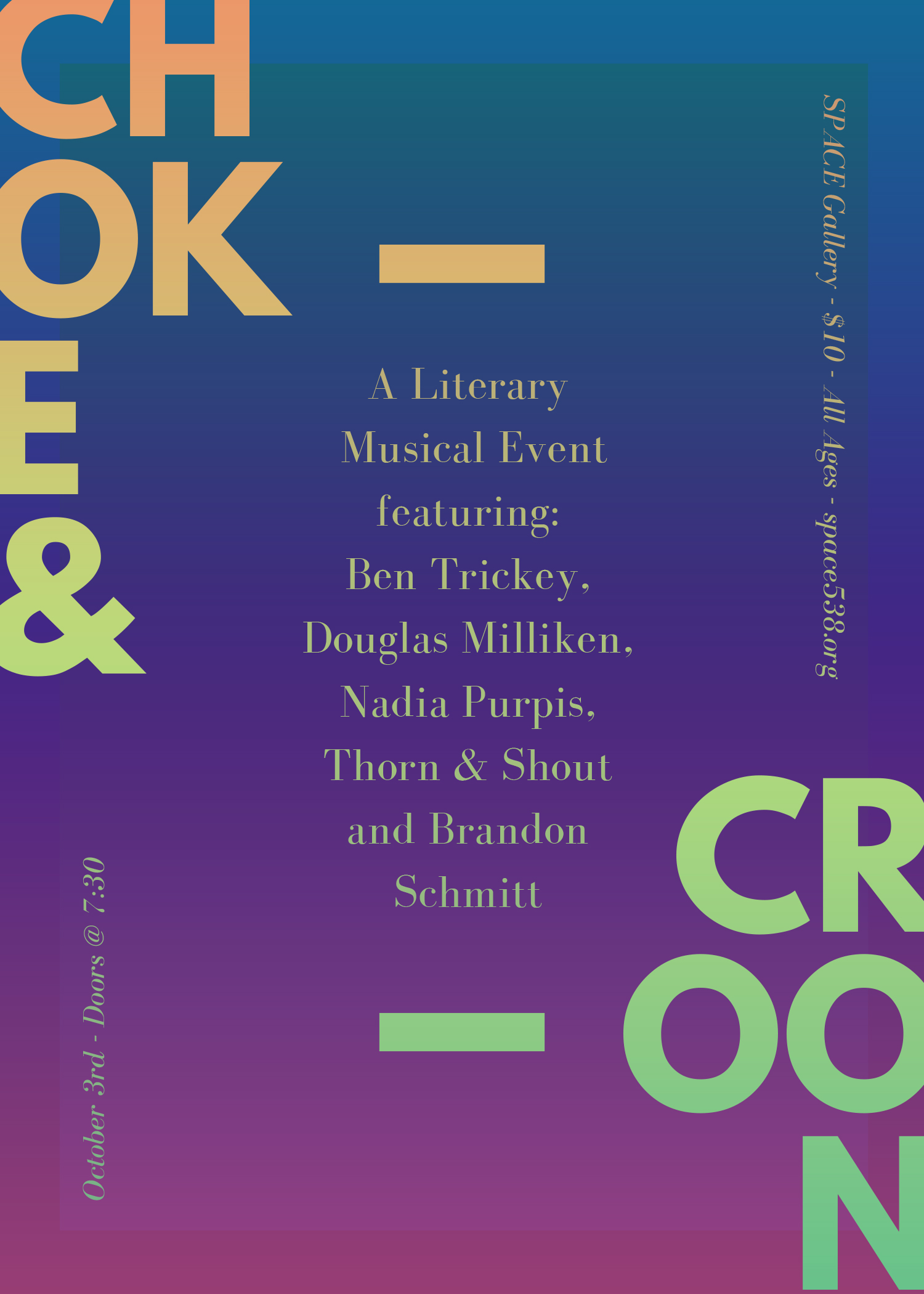

In anticipation of our mixed literary/musical event on October 3rd with Nadia Prupis, Thorn & Shout, and Brandon Schmitt of Delta Sierra —an event titled, not coincidentally, Choke & Croon after Ben’s most recent record—the following conversation took place over a series of emails between September 20th and 22nd. —Douglas W. Milliken

*****

Douglas W. Milliken: Your music increasingly exists in this fascinating intersection of down-tempo indie rock (bordering occasionally on monstrous shoe-gazer assaults) and alt-country, employing a lot of the traditional motifs of that genre (slide guitar, fiddle, etc.). Which I gather is not unintentional. You’ve even said in the past that you want to distance yourself from the limitations associated with the alt-country label. Yet you’ve been married and divorced a whole bunch of times, burn through dogs like they’re strike anywhere matches, and write songs that include, not just bars, but actual bar stools. All of which sounds pretty damn country to me. Explain yourself.

Ben Trickey: I’m southern. This is a fact I have tried for a long time to run away from, mostly when I was a high school kid in Alabama and had no inclination toward football or your typical camouflage-hat machismo. I was an outsider and I loved fringe culture. As I got older, I settled into the fact that the southern is in me no matter what. Trying to do country, to me, felt like I was doing a period piece or falling on a shtick, a costume. There’s a whole scene of alt-country or down-home style music, singing songs about hopping trains and sipping whiskey, watching the dust-bunnies blow by. Mostly by folks who don’t live those lives, but are referencing them to present some kind of style or motif. Now, I’m not bashing that stuff. I listen to some of it, but personally, I want to present something that feels more current. Something that isn’t hung up on imagery from the past. How can you write a song that’s timeless and current at the same time? I have no idea. I just like to revel in the absurdity of existence and make enjoyable introspective ditties about the end of it all. I also have an ex-wife and my dog just died. Thanks for bringing it up.

DWM: Change “Alabama” to “Maine” and “football” to “basketball,” and you’ve pretty much described my youth and consequent drive to write stories about anyplace but Maine. Yet here I am, too, writing stories about home. I wonder how much we’re each following a natural impulse to explore a time and place we weren’t allowed to appreciate or experience fully as kids, or if we’re possibly cross-contaminating each other’s art. I mean, we’ve never directly collaborated on anything, but you wrote the foreword to Cream River and I’ve written press stuff for you, and moreover, we’ve been sharing work for something like fifteen years: some of the ideas and characters in your songs have certainly helped shape ideas and characters in my stories.

BT: There’s this great thing you do in your stories when something horrible happens. It just happens. There’s no dramatic build-up or need to circumvent the action from every angle. It’s almost like it happens in passing. That is something I’ve always been interested in and use in my songwriting. I used to think that way of looking at bad things was some kind of maturity. Like, here is this unfortunate event…let’s recognize it and move forward. There was this review of my last record at Popmatters that sort of nailed it. He mentioned I had this “elder persona, the weary voice of experience,” and my themes address the “vagueries [sic] of Southern masculinity, often questioning both how to live up to that model and at what price.” I feel like your writing has very similar machinations, which is why I love our creative trade-off over the years. I feel like we’re both painting the same stark landscapes. We’re likeminded and I feel right at home around your work.

DWM: Yeah, I definitely think what we’re doing increasingly falls into the category of world-building. Each song or story might stand alone and live its own life, but when taken as a whole, something greater (hopefully) emerges. I feel like I can safely blame my teenage self’s steady diet of concept albums and Stephen King novels for that impulse to make everything connected to everything else. Or maybe I just have a hard time letting go of characters after spending so much time thinking about them (likely another impulse rooted in my adolescence).

BT: I know you make music as well and I’d be curious if your writing sensibilities move into your sonic explorations.

DWM: To a degree. The songs that I wrote as a companion to the stories in Cream River, at least in my head, act as a sort of abstract expressionist version of the characters’ thoughts and feelings and motives. They’re acting as a mirror to, or maybe an alternate take on, certain moments or people or places. Which maybe isn’t too different from your tendency to release multiple versions of the same song? The stripped-down performances of “The End of it All” or “The Darkness (Don’t Know Nothing)” that you recorded as part of your series of 7″ records, for example, tell a different story than the studio recordings on Rising Waters. The same with the different versions of “Tangle.” The words are the same, the chords are the same, but the delivery gives the songs new meaning, new shape, sometimes presenting a deep ache and sometimes an acceptance or resignation. Which I think is beautiful, and also true to life: the story is never just the story.

BT: Totally. I grew up obsessed with comics and sci-fi/monster movies, so continuity is a big thing for me. If you give some information over here of what happens, then jump to another point to tell another event, your brain opens this whole world of what is happening between the two moments. It makes it feel bigger by suggesting all the stuff you haven’t even mentioned. I’m really into this idea as a sonic exploration as well, which is why silence is a big thing for me. It’s an instrument in my band, [a way of] exposing the guts of the thing in the thing.

DWM: Right, because it’s not really silence. It’s a room full of people trying not to move or make a sound, all to a shared silent beat. Which I think is kinda the definition of tension.

BT: Yeah. That tension can happen on a different level listening in a car or at home, too. To me it’s a purposeful frailty that presents an intensity, and thus empowers a new strength in it. That may be too pretentious, but it’s something like that to me. You can feel the fibers snapping.

DWM: Issues of work come up a lot in your music. Hanging out at the bar is a pretty common motif in country music, but in your songs, the listener is never not aware that this is an escape from and a result of working a job, of having bills to pay for things you maybe never even wanted. Is this a pedestrian “write what you know” sort of thing, or are you digging at something more?

BT: Well, it’s a bit of both. I feel like a lot of music is yearning for peace or some kind of heaven. It’s the gospel, so to speak. For me, that Promised Land only comes in small bursts at the bar or when you can enjoy the wind blowing or whatever. It’s sort of these little heavens you get when you can. You had a short story you sent me once. I think it may be in White Horses, but the main character sees a dog tied up and no owner around. He sits down and unties the dog and watches it run and thinks how nice it must feel to run. That’s the same concept I try to present. That kind of yearning.

DWM: I remember that scene, though not the story. Definitely something I wrote when we were still in college. It’s one of the fun—and also dangerous—things about writing in the first person (a narrative device that’s something of a given in songwriting: “you” are telling us something, and no one questions the veracity of that voice). That character gets to construct himself as some kind of wistful good guy, waxing poetic about some idyll of freedom. But dude just set someone’s dog loose! It’s like your song “Horror Movie” on Pretty Little Wave. The narrator is trying to express an intimacy and deep yearning, and that definitely comes across. But less obvious—and this is the dangerous part I mentioned—is the lurking menace throughout the song. It’s easy for someone listening to feel like something lovely and sweet and innocent is going on. But you have to remember: this dude kinda wants to kill you.

BT: Yeah, there is a duality to it. Like the escape is there for the taking, but you may have to drop the ball somewhere or step on someone else to do it. This yearning can be a dangerous thing. It causes conflict when acted upon. If there wasn’t any problems in escaping or indulging, it would be way easier and may not offer the release you’re looking for (whether you are setting something free or eating someone alive).