We used to spin globes, closing our eyes and dragging our fingers across the rotating surfaces. It was an activity equal parts discovery and escapism. Beneath our index fingers, the raised topographies of the world’s mountain ranges spun by, the globe’s rotation slowing to a halt against the friction of skin-to-cardboard contact. Tiny, obscure place names were revealed under fingertips: Qaanaaq, Greenland; the island of Tristan da Cunha; the Sea of Okhotsk.

We traveled by map like Indiana Jones, imagining ourselves on alternate latitudes, hemispheres and continents without any real idea of what life might be like in those places. We tried to picture a town in the Arctic Circle, a miniscule island in the South Atlantic Ocean or the cold waters off the Kamchatka Peninsula. Everything must be so different, we thought, wondering if we’d ever step foot in such far-flung locations.

Since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus became a pandemic, infecting people on every continent but Antarctica, escaping the disease means not fleeing to another point on the globe, but retreating into a personal bubble with a 12-foot diameter. Weathering this health threat requires retracting within oneself, behind a mask, into the safety of private space shared only with trusted loved ones—if we’re lucky and privileged enough to do so.

We’ve dealt with these new constraints in myriad ways, and artists, never a homogenous group, have created equally diverse responses to their physical, material and social limitations. But what struck me the most while clicking through BROADCASTS’ map of submissions is the strangeness of a communal experience on this scale. Spin the globe now and anywhere in the world, the residents of that village, island or peninsula are living within the coronavirus pandemic.

We are all in this terrifying thing. While we may still be separated by language, geography, power and history, the artwork of BROADCASTS was made under shared conditions. In these communications sent across vast distances, we see evidence of the closest we may come, in our lifetimes, to a truly global experience.

The internet, not always free and democratic, is nevertheless a key element of this. Even before the pandemic forced us out of public space and into digital meeting rooms, we’d traded many of our physical endeavors for a few clicks of the mouse. The internet has taken the psychic place of those exploratory globe twirls; the scroll is the new spin.

Within what is often a morass of hateful and/or corporate-controlled content, it’s heartening to see artists carve out a space on the internet for chance and reflection. Preguntar, Lissa Corona and Marina Grize’s stark website of all-caps text acts like an oracle, with a list of prompts for deep thinking. Does someone have to be in charge? What is nostalgia? Who decides a punishment is deserved? These are questions for any moment, but the pandemic and ongoing uprising for racial justice lend them an urgency we realize they always needed.

I play the globe-spin game with Preguntar, positioning my cursor near the left-hand margin and letting loose a wild scroll. What is a choice? For many of the artists in BROADCASTS, choice is now a luxury. They write about being stranded and displaced—not at school, not in the studio, not at work, suddenly a full-time parent, stuck in other people’s homes.

Poet Lily Kipp captures the discombobulation this out-of-place-ness often engenders in creative routines: “On some days, I can write and edit my work for hours, submitting to any magazine I can find. On other days it’s hard to open my laptop for anything but watching TV.” Grief is both a motivator and a hindrance. Screenshots of her desktop are woefully familiar to me: layered windows of text, the result of “ebbs and flows of creative capacity,” as she beautifully describes it.

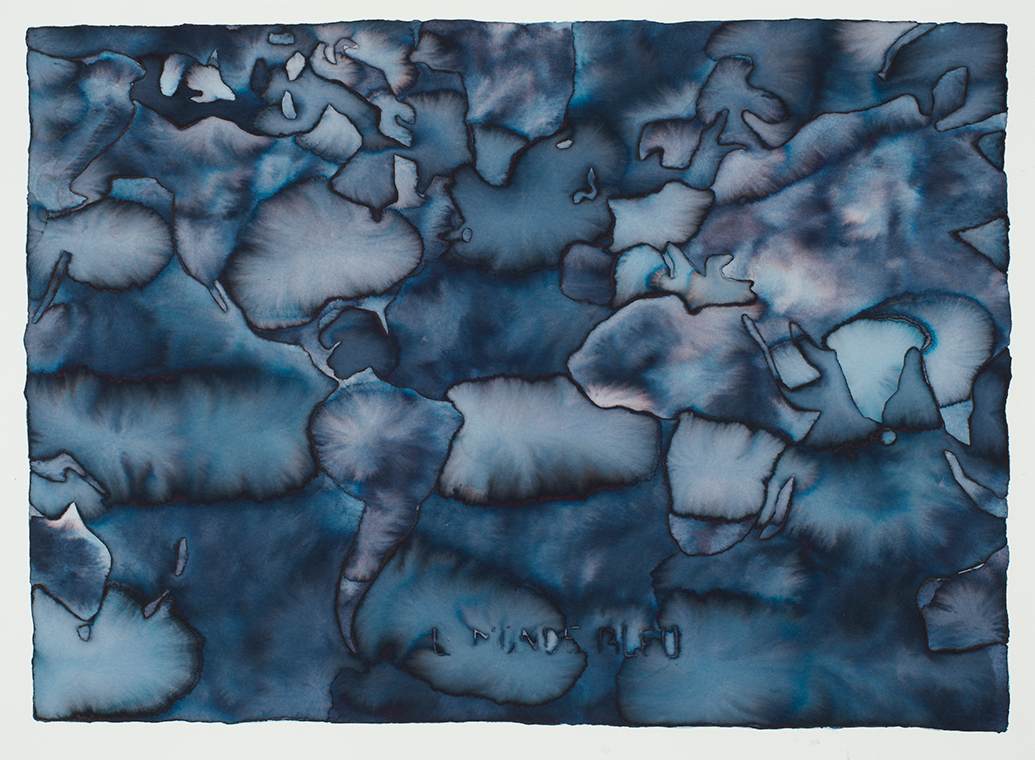

There’s definitely something watery to the way time passes during the pandemic. Hard edges blur as one hour, one day, one week or month flows into the next. Sam Mapp’s inky, bruised watercolors, a project begun well before the current crisis, have become prescient, both in their subject matter and his mode of rendering it. First, the world map: Mercator projections, those old standbys, render our globe two-dimensional and rectangular, wildly distorting land masses the further they get from the equator. This familiar view of the world was always full of inequities (for instance, the size of Greenland versus the entire African continent), but now we check on versions of it daily, inequities laid bare by the spread of a virus. Each new hotspot points to an underlying, systemic failure: to provide personal protective equipment, to keep children safe, to house people, to offer a living wage, to take care of our most vulnerable.

Like Preguntar, Mapp’s watercolors employ chance, allowing pigment and water to mingle and flow. The boundary lines between land and water are there, but more malleable than we’re used to seeing the world, ordinarily represented in blocks of interlocking pastel shapes. Mapp captures the movement of water, but also air, people and goods—the movement that makes our globalized economy possible and also so very vulnerable.

Heather Lyon is also interested in the watery edges of things, where she attempts to communicate not across vast distance, but with the distance itself. In her video SEMAPHORE LOVE LETTER – Nazare, she stands with her back to the camera on a Portuguese beach, moving her arms through the angular poses required by the flag language of semaphore. Alone with the pounding surf, she wears a mylar safety poncho, a strange, spacey outfit that makes her communication with “the great beyond” all more alien. “I am declaring my love to the mountains, and to the sea, to the unknowable in myself, and in you, and in everything,” she writes. This is no Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, Caspar David Friedrich’s romantic painting of a young man overlooking a vast and craggy landscape. Lyon’s relationship to the ocean is one of sincere, almost comedic attention. She signals her missive without ever turning to acknowledge us, the viewer, inviting us to similarly contemplate the broad expanse of the Atlantic Ocean and put our own connections to it into words.

In a love letter to a very different landscape, Rose Marasco’s stop-motion video of a train ride from New York City to Utica traces another line across a map—a well-worn and personally significant journey. We all have these routes, short or long. Traveled during formative times, they cut deep grooves in our memories. Following the Mohawk River between Albany and Utica, this 37-second video captures, even in its short runtime, the gray of a December day, riverbanks dotted with snow, the trees dark and bare. Somehow, in fleeting images, Marasco captures the impatient feeling of nearing home, a feeling that exists even when you’re far removed in physical space and years. “The landscapes of our youth imprint on us a certain deep feeling,” she writes.

We know it’s true. The youngest of us experiencing this pandemic will have very different youthful landscapes. Poet Mike Bove writes to his two boys: “Remember how you got to know our house from every corner, saw all the spaces and places where small cracks began to form.” This simultaneous expansion and retraction of space is hard to wrap one’s head around. We have been more still, more removed and more quiet during these past months than at any other point in the history of recorded seismic noise. And yet we see—in the maps and the data points and the shared experiences—how close we are to every other person on this planet. This is what I hope we carry with us through the months and years to come. The word “after” now feels like a jinx, and yet time will pass until we get to something that might be called an “after.”

“Remember that I tried,” Bove continues, “and that, when they closed the borders we opened our own to let each other in from a distance to wander under a single sky, waiting for it all to be a story we tell, something we only remember.”

About the author

Sarah Hotchkiss is an artist and arts writer in San Francisco. Recent projects include the solo exhibition Sleuth at Friends Indeed, San Francisco; You’re weird for building this, a two-person show at Royal NoneSuch Gallery, Oakland; and Space Travel Sci-Fi Style, a performative lecture at the Exploratorium, San Francisco. She has attended residencies at Skowhegan, ACRE and the Vermont Studio Center. She watches a lot of science fiction, which she reviews in the semi-regular publication Sci-Fi Sundays. In 2019 she received the Dorothea & Leo Rabkin Foundation grant for her coverage of visual art in the San Francisco Bay Area. She is the senior associate editor of arts and culture at KQED.