A set table. An old photograph. Your great-great-grandmother’s raggedy tablecloth. Old familial items often evoke feelings of collective memory and community in the same ways that dance can. We often dance to forget, to resurrect ideas, feelings, and memories, or to preserve the ones we have collected along the way.

Rummage Lane is an original dance-theater piece by Portland-based artists Kelsie Steil and Hannah Haines, exploring object-memory and intergenerational relationships. Rummage Lane was funded in part by New England Foundation for the Arts’ New England Dance Fund, with generous support from the Aliad Fund at the Boston Foundation.

The duo present the piece at SPACE on Sunday, November 19th, with two work-in-progress performances at 1 pm and 5 pm. More info and tickets here.

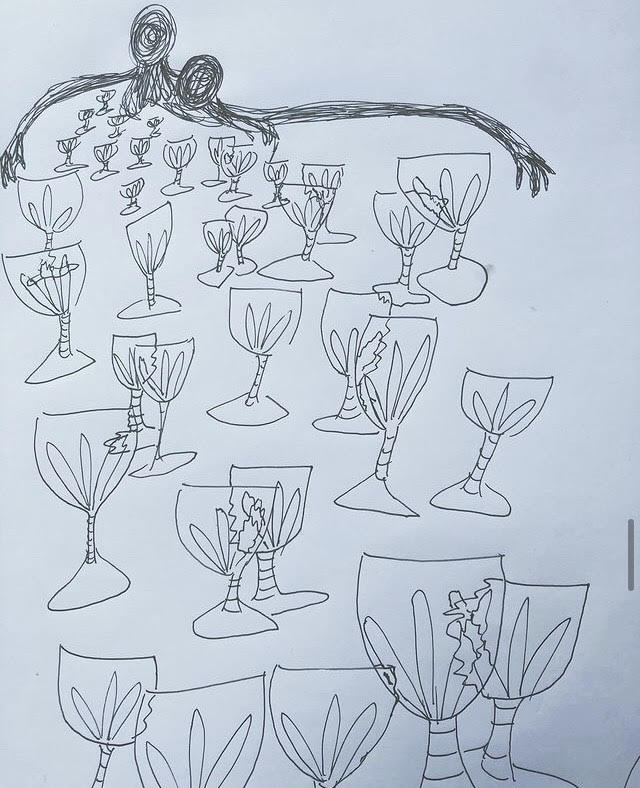

Rummage Lane taps into researched methods of finding community through physical objects and examines how the past informs our present and our future. Through a collection of accumulating chalices, the work crafts a series of scenarios that demand the excavation of the dancers’ cognitive and physical relationships to the past through these objects in a deeply sculptural and physical work.

How was Rummage Lane conceived?

KS: I’ve had this concept in my notes for a long time. If I ever have an idea, I’ll just put it in the notes section on my phone or write it down. I also started by drawing illustrations of this idea, one of which was essentially a bunch of abstract wine glasses with shadowy, scribbly human figures over them. From there, I asked myself if this could be an object study in the form of a theatrical dance work. Things started to take shape and take on full color when I approached Hannah. I wanted to create something with her because she’s such a smart dance creator, and I knew that this would be a successful project in partnership. And when I say success, I mean a fulfilling process that has great depth and has some performance opportunities. So it started as a note and a drawing, then Hannah and I started having meetings and we started rehearsal last year in October.

HH: I studied anthropology in college, so anything having to do with anthropology and material culture gets me excited. I was excited about the idea as soon as Kelsie approached me. As of now, the project has turned into an exploration of the chalices as portals, and exploring the idea of the “family dinner” and the dynamics that objects have in our lives. That’s the nucleus of the project at this moment in time, but there are so many different avenues that we’ve explored in this process. From a more stagecraft point of view, we’re looking at playing with theater and dramaturgical tropes. We’re playing with sets, we hope to play with lighting, and want to focus on the more sculptural elements of the piece. So yes, there’s that sort of crafting side of it that we’ve been really lucky to get to explore.

KS: We researched vessels in a ritualistic context, looking at ancient Middle Eastern vessels to more European dinner party glasses. For most of the project, we’ve been in a deep research mode. We’re now entering the zone where there’s more rigor and dance. It’s been a cerebral process, even still. In our current stages of crafting this piece, it’s been fascinating to explore the compositional and sculptural aspects of this work. Now it’s amounted to about 300, plastic, patterned chalices on the stage. There are two massive clumps, and around the perimeter of the stage, there are more glasses. So it’s a very theatrical piece, and we’re leaning into that.

What are your relationships to props?

KS: The original concept always started with glasses in mind. Early on, we did a work-in-progress showing of the 10-minute version, where there were barely any props. It was just our bodies embodying archetypes of the masculine and feminine and then navigating how we treat different objects and spaces around us. But I think we’ve always had in mind that we would be ordering many, many stage chalices.

Did you always know that you were going to use that specific glass?

HH: During our process, we were always talking about objects that create community, so we didn’t necessarily have only the chalice in mind. We talked a lot about gathering places as central beacons. I remember when the first phrases that we came up with in rehearsal looked at the idea of a bonfire. There were a lot of different ideas of community and of objects that represent places where we gather that we talked about, but I think pretty early on, we came to the idea that the chalice is an effective stage prop. We were really excited about the idea of playing with them against the light because of their reflective properties.

That’s awesome. How did you both meet? How does it feel to have met a collaborator that you can make such intimate work with?

HH: When I moved to Maine from New York during COVID, I was reaching out to some different folks and thinking about what I wanted to do as a next step in my career. I graduated in 2019 and was in New York for a very short period. And then COVID hit. I was deciding what next steps I wanted to take as a creator. I was reaching out to different mentors and people who I had connections with. Someone told me ‘I think you would get along with Kelsie, she’s such an interesting mover, and you’re around the same age’. And that was a couple of years before or a year or two before I actually met Kelsie. I was like, wow, she’s cool. I’d like to work with her. She puts a lot of work into her craft and the technical aspects of her career. She’s definitely the driver of all our photos. Our collaboration works so well because we have different things that we’re excited about that are all part of the work of being a choreographer. So I was like, wow, she’s cool. And then we met in person at a Ballet Bloom Project, which is a project-based, contemporary ballet company run by Rose Hutchins.

KS: I met her doing projects with Rose Hutchins of Ballet Bloom project, and we danced in some pieces together. We were colleagues in that space and had a good time. We connected and I noticed we had a similar embodiment of movement. I was drawn to the way she moves as an individual, and felt like I would resonate well with her dance-wise.

Considering that the piece heavily relies on these concepts of time and concepts of memory. How do you want the work to evolve as time passes as you guys create?

HH: Something we’ve talked about is understanding who we are positionally while creating this work. We’re both in our twenties, and there are a lot of parts of life that we haven’t experienced. This is a completely different work than the same concept that we would have made if we had come together when we were in our 50s. And so being aware of that we made some intentional choices regarding the set. One of the props on the stage is a tablecloth, and there’s an opportunity for that tablecloth, you know when we found that when we moved it around it in certain ways were like ‘Oh, it can look like a baby’, but we realized that the idea of motherhood is not something that we’re ready to explore as choreographers because it’s not something we’ve experienced. And although this is a very cerebral work, and we did do a research process, ultimately we’re trying to portray things that we’ve experienced. A lot of the non-chalice props were taken from my family home, so there are literal memories attached to them. So it does read these actual conversations that are what the piece is about, and we try to bring that knowledge with us in the way we embody the dance. We are creating a piece about our experience with all of these concepts as we are now. It’s an interesting question: if we want to continue to do this work, will we continue to change it as our relationship with some of these objects changes as we age?

Awesome. Do you guys ever find it difficult to tap into that kind of vulnerability on stage that you need to have for work like this? How do you get into that vulnerable space on stage?

HH: The short answer? It’s scary. Something I talk about with my dance students is that as artists, you know, a lot of times, we don’t want to get into our red zone, but we can’t live 100% in our green zone. And so there’s going to be a lot of living in your orange and yellow zone as an artist. It’s really important for longevity to recognize the days that you need to be in your green zone. Working with a partner who is not only a great collaborator, but a great friend makes that easy because she knows the days to push and when not to push. There’s a difference between feeling a little uncomfortable in a way that’s going to be exciting and healthy and pushing your art. Sometimes it’s not the day to be vulnerable. Having those conversations about mental health and dance is important.

KS: I’m working on that all the time. The relationship between her and I has grown so much, and it’s such a blessing when you can learn how to navigate another person. Dance is an amazing vehicle for that. When building a project there is inherently so much work. There are so many facets to this work that we’ve had to do other than just showing up to rehearsal. Vulnerability is something that comes naturally to me. But regardless it’s scary before you step on stage, or before you share an idea with someone, even if that person is a friend. But I would say everyone’s green zone/red zone is different. And that’s also cool, right?

What advice do you guys have for artists who want to kind of step into the world of multidisciplinary Dance/ Dance Theater?

KS: I would say have resources in place. Team up with fellow artists that are not necessarily in the dance discipline, and have open conversations with them. For example, someone in the photo and video realm, someone who’s into dramaturgy, etc. Whoever you’re working with should share some of your strengths as well as fill in each other’s gaps. Asking questions is also important, and don’t be afraid to talk to former professors or dance teachers. Also just really, really enjoy the concept you’re putting forth. Find ways to make the concept concise so you can dig into your work. And, of course, try to believe in yourself and your art.

HH: Yeah, and I’d say from the artist’s perspective, particularly as a dancer, I didn’t do anything other than ballet until I got to college. Being a dancer can become an identity for a lot of people. I’m a dancer, but I’m also a thinker. And maybe I’m not a *trained* actor, but I have feelings and have learned to express myself theatrically on stage. We are taught that to succeed in dance, you have to have these certain traits, like discipline, and being willing to follow. So sometimes knowing that you might need to shake off some of those dancer traits to get into the realm of doing something more abstract is a big part of it. If Kelsie had approached me a couple of years earlier, I would have been like, oh, ‘I don’t know if I can really do that.’

KS: Breaking out of the boxes we put ourselves in, and reminding ourselves that we can make our own boxes, is important. What’s great about producing your own work is you can find places to grow as an artist, and in an athletic body, and you can also lean into what your strengths are. And, you know, I have a slight acting background, so I care about pushing the theatricality of the work. But that’s my personal preference and goal. And so when we’re talking about a dance theater piece, I mean, one can make their work lean more on the side of the traditional balletic form, or you can go more into the theatrical side, it can be anything you want it to be.

Image Credit: Maxwell Auger