Re-Site 2024 | Rachel Alexandrou – Aggregate

Rachel Alexandrou

June 3 - Cake for Birds: 5-8am and 6-8 pm, plus additional time with the artists present

June 4 - Feast for Humans: 6-8 pm; Register here, space is limited

June 3 – Cake for Birds: 5-8 am and 6-8 pm, plus additional time with the artists present

June 4 – Feast for Humans: 6-8 pm; Register here, space is limited

Rachel Alexandrou’s Aggregate highlights the importance and beauty of native species and the urgency of ecological change and awareness. This project explores the history of Portland’s significant role in the production and trade of bricks, which formerly took place at this site. Ahead of the events, Rachel will be forming wildflower brick sculptures composed of herbaceous native seeds that are specifically chosen and beneficial for this specific habitat, and made of organic dissolvable materials while also temporarily installing a bird feeder. In addition, Rachel will be making a recipe for birds that contain wild seeds and fruit for the first event, Cake for Birds. The public is invited to observe and birdwatch during active bird feeding times and observe the feast. The second event, Feast for Humans will be a guided walk about the ecology and geology of the area, with a series of stations for learning about the plants and soil with foraged recipes and plates made by artist Josh Clukey made by foraged clay from this site and leftover from the historic brickyard (these can also be purchased). Deep geologic time, the time of brick production in Portland, current time, and future time will all be examined.

Rachel Alexandrou is an interdisciplinary artist who uses her education in plant science, and collaborative practice, to create experiential work about food, flora, and innovating human relationships to the natural landscape.

Re-Site 2024 is made possible with the generous support of the Mellon Foundation’s Humanities in Place initiative.

SPACE is pleased to present Re-Site 2024, the second iteration of the site-specific, temporary public art and Portland history-telling initiative we first launched in 2020. This year’s series features artwork by James Allister Sprang, Maya Tihtiyas Attean, Ashley Page, Rachel Alexandrou, and Ling-Wen Tsai, in collaboration with historians Seth Goldstein and Libby Bischof.

Each of these 5 artists were nominated by the previous group (Asha Tamirisa, Shane Charles, Heather Flor Cron, Veronica A. Pèrez, and Asata Radcliffe) and selected a site within the Greater Portland area to propose a temporary public installation or performance in response to its history.

During the first iteration in 2020, the idea of Re-Site stemmed from the Maine Bicentennial, quickly becoming more urgent and relevant due to the growing call for change across the intersections of civil rights, climate change, public health, and political process. In the four years since these first activations, we are thrilled to bring these new projects and histories to light in order to broaden our knowledge and awareness of these local histories and understand how their impact has brought us to where we are today, through various artistic lenses. Our hope for Re-Site 2.0 is to further expand and engage upon what we first started, and broaden the artistic possibilities to demonstrate “and generate dialogue about what we want to carry with us into the future.”

Re-Site 2024 is made possible with the generous support of the Mellon Foundation’s Humanities in Place initiative.

Re-Site locations, schedules, and details:

Please take note that each site has specific days and interpretations it will be viewable to the public. All sites will feature a Re-Site lawn sign, which will include information to see the full artist statement, site history, photo and video documentation, and a bibliography with further research on key related objects viewable in public collections. Documentation will be regularly updated and archived on the individual project web pages linked below.

Site History: Portland Brick Co.

Brick production in the state of Maine

Densely populated 19th century cities grappled with ever present danger of fire. Portland, for example, suffered from the largest city fire up until that time in the U.S. in 1866. To ameliorate this danger cities were increasingly built with brick. Maine had many small kilns across the state. A kiln could be built along the coast or aside any river or stream that had bands of clay along its exposed bank. Today the remnants of clay bits and pieces of brick are evident along numerous bodies of water. Brick-making became one of the many seasonal endeavors on family farms throughout the state. As a result of glacial activity, Maine’s clay deposits contain a greater amount and variety of minerals than clay from other regions. The resulting bricks were not suitable for high temperature or industrial uses but were highly desired for other building purposes.

The process of brick-making involves cleaning clay of any debris and allowing it to dry in the sun. The clay is then mixed with water to produce a slurry that is poured into wooden molds. At this point the bricks are referred to as “green.” Once the “green” bricks have dried they are stacked into arches forming a kiln that a fire is built under. The bricks would be fired for a week or longer. The firing process would convert the clay from a gray color to an orange or red hue. This process eventually became mechanized at larger brick manufactures who employed devices such as the “Hobbs Mud Machine” to streamline the process.

The town of Brewer became a major manufacturer and exporter of high quality bricks. The city is located across the Penobscot River from Bangor which was the lumber capital of the world in the mid-19th century. Brewer brick makers used scrap wood from across the river in their kilns. The resulting bricks were of such high quality that they became the standard in U.S. buildings. Government contracts stipulated that buildings be built of “Brewer brick or equal.” In 1886 the town boasted 11 brickyards that produced an estimated 9.4 million bricks a year.

Bricks became a major export commodity in Maine with ship captains using the heavy bricks as ballast in their vessels. Maine bricks were shipped to major U.S. cities such as New York and Boston and were exported to Europe and the West Indies.

Brick use in the City of Portland

According to William Willis in The History of Portland, “…in 1785, 33 dwelling houses were built; these were all of wood except Gen. Wadsworth’s on Main Street, which was commenced in 1785 and was the first ever constructed wholly of brick in this town…In 1798 Henry Titcomb built the brick stores on the corner of Union and Middle streets, two in number, which were the second of that material constructed in town.” A footnote at the bottom of page 563 notes, “The first [brick business] was erected by Samuel Butts in 1792, connected with his house on the south side of Fore street, a little east of the passage way on to the Pier. Mr. Butts was a tailor…”

Fore River and Portland Brick Company

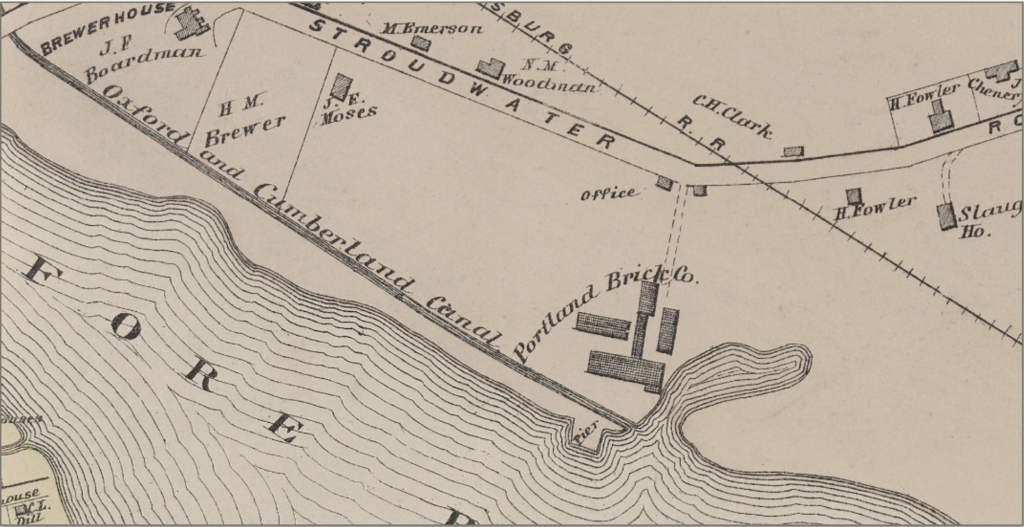

The Portland Brick Company sat on the banks of the Fore River close to Stroudwater Village. Stroudwater was spared the bombardment of Portland by the British during the American Revolution and the Great Fire of 1866. Hence the oldest building within the boundaries of Portland is located here. The Tate House was built for the King’s senior mast agent, Captain George Tate Sr., in 1755. During the colonial period the river would have been the means to convey giant “mast logs” to Clark’s Point along the harbor. The Portland Brick Company was located near the Portland terminus of the Oxford and

Cumberland Canal which was completed in 1832. The canal brought goods back and forth between the port of Portland and the interior of southern Maine.